Amazon - Website

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Sundry Great Gentlemen: Some Essays in Historical Biography Author: Marjorie Bowen * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1305811h.html Language: English Date first posted: Sep 2013 Most recent update: Dec 2013 This eBook was produced by Colin Choat. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

"Les hommes sont rien, un homme est tout." —Napol?on I.

"Let us now praise famous men...such as

did bear rule in their kingdoms, men renowned for

their power...leaders of the people by their

counsels and by their knowledge...all these

were honoured in their generations, and were the

glory of their times." —Ecclesiasticus, 44.

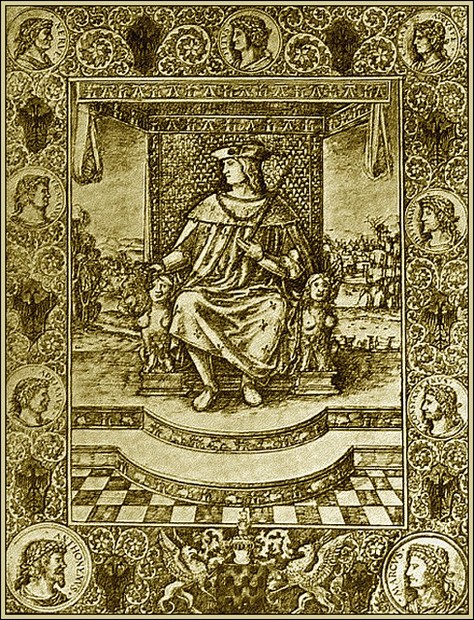

Louis XII of France, Louis II d'Orl?ans

THE following biographical sketches may find some excuse in the fact that five at least are not well-worn subjects to the English reader, and all deal with characters of singular interest and wide importance in their several times.

The endeavour has been, in each case, to detach the man from these times, a task not always easy: the individual is so apt to be dwarfed and even hidden by the events that surrounded his personality.

For this reason the complications of the Thirty Years' War, those of the Austrian and Spanish Successions, are dealt with as slightly as is consistent with a coherent relation; details of these and the other historic happenings referred to will be found in the books quoted in the bibliography that follows each subject; these bibliographies, though of course by no means exhaustive, cover a fairly wide range and will afford a comprehensive amount of information.

The subject of the spelling of foreign names must always be a vexed one; without pedantry one must be capricious, for rio satisfactory fixed rule on this matter has yet been found; the author has used the usual accepted English spelling of most well-known proper names, and here and there the foreign forms when these referred to less familiar people or places and appeared to give more life and colour to the narrative; there may be a great virtue in the spelling of a name, and the author was loath to sacrifice Carlos and Dom Sebasti?o and only reluctantly gave up Loys.

On the other hand, Gustav Adolf and Hermann Moritz von Sachsen savoured too obviously of affectation; the usual compromise on this difficult question has therefore been adopted; whatever way is chosen the author generally comes in for criticism, which this explanation is not so hopeful as to expect to disarm.

There are no portraits, of course, of Frederic II and few of Dom Sebasti?o; none of those of Louis XII support his contemporaries' opinion of his good looks, and those of Maurice de Saxe are also disappointing though characteristic of his flamboyant period.

On the other hand, the portraits of Carlos II and Gustavus Adolphus II are abundant and fine; most interesting both as historical documents and as likenesses, though, even here, neither the ugliness of the one nor the beauty of the other is so apparent as one might have expected.

Many of these stories contain, oddly enough, a mystery; in each case the sensational explanation has been rejected or ignored, because there seems to be slight foundation whatever for it in every instance.

The conspiracy of Pietro da Vinea is obscure beyond hope of elucidating now; but many tales have grown up round the death of Dom Sebasti?o, of Marie Louise d'Orl?ans, of Maurice de Saxe, the fall of Gustavus Adolphus at L?tzen.

Did Sebasti?o return to Portugal long after the disaster where he was supposed to have perished?

Was Maurice de Saxe killed in a duel with the Prince de Conti?

Was the Queen of Spain poisoned by the Austrian party in Madrid?

Was the great Swede treacherously slain in the confusion of the battle?

There seems little evidence for any of these suppositions, yet a doubt will in all the cases continue to linger, until the day when some industrious researcher of archives puts the questions at last beyond dispute, as one such worker appears to have already put the question of the death of Dom Sebasti?o.

The author, in dealing with these debatable points, has not followed the romantic tradition of accepting anecdotal tales, which, however often repeated, only rest on dubious evidence and are obviously embellished by fancy, but has tried to keep as near the truth as is possible in following authorities so often conflicting.

It may be noted that many of the terms used, "balance of power," etc., express conceptions of political economy now outworn, but these same conceptions were very powerful in their day and embodied ideas that swayed the statesmen of Europe up to the period of the Congress of Vienna; they have therefore, though obsolete at the present moment, been adopted.

M. B.,

London, August 1927.

Frederic II of Hohenstaufen.

Emperor of the West, King of Sicily and Jerusalem, 1194-1250.

"Stupor Mundi et immutator mirabilis."

"I hold my crown of God alone, and neither

the Pope, nor the Council, nor the Devil shall

rend it from me...I who am the Chief Prince

of the World, yea, who am without an equal."

—Frederic II at Turin, 1245.

IN March, 1212, Frederic of Sicily sailed up the Tiber with a small retinue; and, landing at Rome, paid homage to the Pope, Innocent III, in the sumptuous palace of the Laterano.

This visitor to the city of the Caesars had come to claim the heritage of the Caesars; he was on his way North to assume sovereignty over the chaotic Empire that Papal gratitude had bestowed on Carolus Magnus and that, revived by Otto the Great, had been carried to a height of splendid pretension by the House of Hohenstaufen of which this Sicilian Prince, the son of the Emperor Henry VI and grandson of the redoubtable Frederic I, called Barbarossa, was the heir.

His mother was Costanzia, heiress of the rich and elegant Kingdoms of Sicily and Naples, and this Frederic had been born on Christmas Day, 1194, at Iesi, in Apulia, while his father was celebrating the Advent of the Prince of Peace by the atrocious massacre of the family and followers of the rebel Tancred; before Frederic was three years old this grim tyrant had died and his widow had put the defenceless boy under the guardianship of the Pope, who took the occasion to seal a hard bargain with her which included the vassalage of her paternal lands and a yearly tribute to the throne of St. Peter.

Even the dearly bought protection of the Holy Father could not, however, secure the Empire to the grandson of Barbarossa, though the Electors of Germany had sworn to Henry VI to elect his son as his successor, and, since the time of Otto the Great, it had been understood that the imperial crown was to go to the Prince chosen by his peers to be King of Germany.

Not only had Frederic been ignored in the competition for this splendid crown, which had been bestowed on his uncle, Philip of Hohenstaufen, by the majority of the Electors and on Otto of Guelf, Duke of Brunswick, by the minority, but a confusion of civil war had been stirred up in his native Kingdom, so that the boy, left motherless at four years of age, was often not only without a realm, but without a home. The protection of the Pope had preserved him from complete ruin and had secured him an education; Sicily was subdued to some quietude and the young King married to Costanzia, widow of the King of Hungary, and sister of the King of Aragon.

Meanwhile, for twelve years a struggle of hideous ferocity had raged between Philip of Hohenstaufen and the Guelf, ending in the success of Otto, who was rewarded with the Imperial diadem; but immediately after the newly elected Kaiser broke the oaths of submission he had made to the Pope and proceeded to harry the lands of the Papal ward, this Frederic Hohenstaufen, King of Sicily and rightful Caesar, now in Rome.

Innocent at once excommunicated the refractory Emperor and fomented divisions in Germany where the defeated Hohenstaufen party was still powerful though subdued.

Otto hastened North from his Italian conquests to crush this rebellion, and Innocent, as a counter move, encouraged the young Frederic to come from Palermo and assume the dignity of his forefathers, in answer to the summons of the Electors, who, weary of the civil war, turned to the young Hohenstaufen for relief.

Such were the events which brought the grandson of Barbarossa to the footstool of Innocent III in the early spring of 1212.

The high adventure to which Frederic had been summoned was perilous and lofty, full of profound dangers, but with the greatest prize in the world as a possible reward; he was reputed to be of a soft and voluptuous temperament, given to elegant versifying and idle pursuits in his warm Southern Kingdom where the traditions of an ancient culture were decaying amid flowery fields, where yellow marble temples dedicated to dead gods still stood amid the wild vines, and where the dark groves of bay and olive, ilex and citron shadowed the meads that Theocritus had peopled with singing shepherds.

Innocent, the shrewd, powerful man of the world, who grasped the keys of St. Peter with as ferocious a grip as the terrible Hildebrand himself, had been doubtful if this Sicilian born and bred Hohenstaufen would be of any use to him in his struggle with Otto of Brunswick; it was difficult for the Pope to find a Prince strong enough to hold together the unwieldy Empire of Carolus Magnus, and at the same time meek enough to be the humble vassal of Rome.

Frederic Hohenstaufen was now seventeen years old, and had been three years married; when the Papal forces had driven the Saracens into the mountains in 1200, and restored some measure of peace to Sicily, the Pope had installed the Archbishop of Taranto as tutor to the six-year-old King; this dignitary was assisted, oddly enough, by infidel scholars and the boy's mind had been formed by Mussulman as well as Christian doctrines; he was unusually accomplished in the liberal arts, but he had disclosed no ambition, and apart from a piteous appeal to the Sovereigns of Europe, written when he was in great misery, at the age of eleven, had made no attempt to interfere in the embroiled confusions of the time.

This King of Sicily had embarked on his ambitious journey with only a scanty following; most of the Sicilian nobles had preferred the delights of their native country to an enterprise so dubious and had not wished to see Sicily become an apanage of the Empire, and when he appeared before the Pope it was with a mere retinue, not an army, and a retinue clad in silk and adorned with an Eastern opulence.

Innocent hoped to put forward this brilliant boy as his lieutenant in Christendom, a position in which the Popes had been striving to put the Emperors since they bestowed the pompous honours of the Caesars on the Frankish monarch who had steadied St. Peter's tottering throne.

It had often seemed since then as if there was to be no peace in Christendom until either Pope or Emperor were crushed, or until both were united in common aims, welded into one vast authority which should subdue the world under the banner of the Cross protected by the consolidated armies of Europe obedient to one supreme Head, the Emperor, who would be, in his turn, obedient to the Holy See.

Such was the ambition of the present successor of St. Peter, nor was it an unmeaning nor pretentious one for the Church, which had kept alive culture and learning, trade and art, during five centuries in the East while Europe crashed in the West.

Europe was still in a state of confusion and required reducing to order and colonizing; learning and wisdom were mostly the monopoly of the Church; it was therefore natural that the Popes should become obsessed with the importance and splendour of their task, sanctified as it was by the magnificent Divine command, "See, I have this day set thee over the nations and over the kingdoms, to root out, and to pull down, and to destroy, and to throw down, to build, and to plant," and that they should passionately desire in the greatest secular power, the Empire, that which they had themselves created, not an insolent rival, but a submissive ally.

Innocent III thought that he had found such an ally in the youth he had protected and educated, who now knelt humbly before the grim old man, reverently renewed the oaths of vassalage made by his mother, and admitted the baseless claim that Innocent had advanced for the overlordship of Sicily and Naples.

The Pope for his part provided the Imperial pretender with men and money and gave his dangerous enterprise the sanction of the Church.

The slim and serene youth then advanced Northwards where a deputy from the Electors had already been sent to warn the great Lombard towns of the coming of the rightful heir of the Caesars, the King of Germany, of Sicily, the Duke of Suabia and Emperor Elect.

The bearer of these proud titles had a difficult journey before him; the country was infested by his enemies, and Otto of Brunswick, though deposed by the Electors and excommunicated by the Pope, was still powerful and counted many of the Princes of Germany among his friends, nor was he likely to relinquish his gorgeous prize without a renewal of the struggle to which fourteen years of most bloody warfare had habituated him.

The Summons of the Diet had come from Nuremberg in the previous October, and Frederic's objective was the heart of Germany; between him and that lay the Italian and German States, many of whom were either Guelf in sympathy or at war with each other.

Frederic did not hesitate before these rampant perils; he pushed forward to his goal with a daring that was as heartening to his friends as it was menacing to his enemies.

His character was not yet completely disclosed; it was known that he was intelligent and accomplished, and it had been just seen that he was as ambitious and daring as befitted his descent, easily the most illustrious in the West.

His present undertaking was well in accordance with the spirit of a restless, tumultuous age, and the glory of his name seemed likely to be linked to the glory of his achievements.

The blend of the German and the Sicilian had produced in Frederic one who was not typical of either race; the boy who was galloping across Italy to his Imperial throne was slight, almost effeminate in appearance with a profusion of reddish blond hair, small features, a pale complexion and light eyes of a singular brightness and clarity; his face had been compared to the calm countenance of the broken statues of Apollo that here and there lingered in ruined shrines in Sicily; but, if his features had something of classic beauty and cold composure, his appointments were Eastern in luxury and profusion: he paraded sumptuously in the embroideries, the jewelled arms, the gleaming silks and fine velvet, the erect plumes and the gold-studded leathers of the East.

Pisa, which held for the Guelf, barred the young adventurer's way, but Pisa's enemy, Genoa, received him; he remained in that opulent and stately city for two months while his adherents endeavoured to secure for him some way into Germany other than the obvious route by Milan and the Alps, for the mighty Lombard city was unflinchingly loyal to the Guelf. Frederic made at last for Pa via, where he was warmly acclaimed, slipped secretly by night to Cremona through a hostile region, gained Mantua, Verona, and from there the Bavarian frontier, having escaped, by the narrowest margin, death or capture at the hands of his swarming enemies.

His following was reduced now to a meagre train and the greatest perils were in front of him; Otto barred the way across Bavaria, but the Emperor Elect showed that judicious blend of caution and daring, that power to judge swiftly and prudently, to act bravely and warily, that stamps the great leader of men; the luxurious and elegant Prince, used only to the soft leisures of Sicily, turned to the West and proceeded through the snowbound passes of the Alps, smilingly endured the hardships of the progress through the almost impassable defiles, and came out, still elegant and composed, in his own Duchy of Suabia, where he was joined by some notable Churchmen, the Bishop of Coire and the Abbot of St. Gall.

The splendid city of Konstanz, towering above her vivid vast lake, now became the pivot of the contest; the Guelf threatened this gateway to Frederic's progress Northwards, hoping to occupy the town and from this basis to drive the daring boy back into Italy.

But Frederic was always surpassingly swift, he dashed on Konstanz, reached the walls while Otto was a few miles away, and imperiously demanded the loyalty and support of the Bishop of Konstanz, an ancient adherent of the House of Suabia.

He was admitted into the city, the gates were closed in the face of Otto, who fell back Northwards disheartened, and the Hohenstaufen had won the Holy Roman Empire.

Frederic marched triumphantly to Basle, nearly all the German potentates hastening to share his success, his train swelling to majestic proportions as he advanced, brilliant, smiling, serene, into the heart of his new Kingdom.

He now disclosed his latent genius; preserving the serene equanimity of a lofty mind, he remained as unmoved by the dazzling conclusion of his adventure as he had been by its dubious beginning, and proceeded to consolidate his position by lavish rewards to his German friends and by an alliance with France, whose enemy, the crafty Angevin, John of England, favoured the cause of Otto, his nephew.

Philip Augustus celebrated this treaty with a munificent gift of money, which Frederic, with prudent generosity, proceeded to divide among the Electors and Princes of Germany.

At Mainz he held a Diet, at Frankfort he was crowned by the hands of the Papal Legate in the presence of all the Teutonic potentates and five thousand loyal knights.

This was in December, 1212; it was less than a year since Frederic had left Sicily, almost unattended, and now he had achieved the summit of all possible worldly human ambition; he was the Emperor, the heir of the Caesars and of Carolus Magnus, the chief of the Holy Roman Empire, which the men who had elected him believed had been "set up by God Almighty, that its Lord, like a God on Earth, might rule Kings and Nations and maintain Peace and Justice."

He was not yet quite eighteen years old and he had been set up "like a God on Earth," the temporal Chief of Christendom.

He ruled directly over the entire area of Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, nearly all Belgium, and the Kingdom of Arles (France to the Rhone) and Northern Italy, and theoretically he was "the lord of the whole world"; Sicily and Southern Italy were his through his mother, and Poland and Hungary were tributary to him; no youth had ever before, or was ever again to wield so vast and real a power: his Empire exceeded that of Alexander of Macedonia, and almost equalled that of Rome at the apogee of her glory.

The next few years were as a glittering, triumphal progress for Frederic Hohenstaufen; he swept through Germany with his resplendent following of kings, bishops, nobles, routed out the supporters of Otto (who fled into his ancestral territories of Brunswick) and rewarded his vassals with the same smiling calm with which he crushed the partisans of the Guelf; his fame became unprecedented, unbounded.

John of England, allied with the Earl of Flanders, rashly took up the cause of Otto, his sister's son, but was utterly defeated by Philip Augustus at the battle of Bouvines, a defeat that lost Normandy to England; and, after this final overthrow of the Guelf, Aix-la-Chapelle surrendered to Frederic, who seated on the throne of Carolus Magnus was sumptuously crowned for the second time.

He had already taken a vow of obedience to the Pope and recompensed him for his assistance by gifts of land in Central Italy and the surrender of various rights to the Church in Sicily, as well as by the cession of some disputed estates in Tuscany. He now, with the silver crown of Germany on his head, the Cross in his hand, and anointed with the holy oil, made a further concession to the known desires of the Papacy. He swore to lead a crusade to the Holy Land, and his beauty, his power, his obvious sincerity moved the packed multitudes, who had just thrice shouted assent to his stupendous elevation, to excited enthusiasm.

Frederic was now in a position almost beyond human ambition to desire and almost beyond human capacity to maintain; he, who had been an obscure, petty King, whose childhood had been passed in poverty and confusion, neglect and peril, found himself elevated to supreme power over all his fellows, and this at twenty years of age.

It was, of course, a height as dangerous as magnificent to which he had climbed; despite the prestige of his birth and the solid advantage of the Papal support, a single weakness in himself might have at once hurled him to ruin. He had to be bold and wary, daring and prudent, at once loved and feared to hold together, even for a moment, his huge and divided Empire; nor was he, at first sight, the type of man to rule successfully warlike and impetuous peoples; the fair and slender youth, trained in Southern luxury, had nothing of the powerful presence, the fierce and overwhelming masculinity that had made his forefathers the natural lords of warriors.

His appearance, his manners and his tastes might well have seemed effeminate to the rough and burly Germans who crowded round the Eagles, but Frederic was easily and without dispute their master; by reason of his intellect and character he was a born master of men, and with this native genius for governance was combined a personal charm, an attraction, a fascination of word and look, too seldom seen with genius, too often the attributes of the shallow and the worthless.

Frederic's Sicilian blood had tempered the grand virile qualities of the Hohenstaufen with a silken grace, an exquisite tact, a delicate courtesy that even the sullen or the ill-affected could not resist; added to this was the serenity of conscious greatness; Frederic never met his equal in worldly rank, nor his equal in intellectual attainments, he was by genius, as well as position, the foremost man of his time.

This air of calm power, this smiling, but indifferent amiability, this equable, finished elegance of manner, together with his accomplishments and his learning, masking an indomitable will, combined to give him a power as tremendous as that enjoyed by the greatest of his ancestors, and a wider fame.

He was exceedingly popular among every rank of the Germans, who saw in him the Emperor who would restore to them that ordered prosperity which they had enjoyed for a short while under the earlier Hohenstaufen, and which had lately been lost in the factions of the Guelf and Ghibelline.

Frederic increased this popularity by a lavish and impartial generosity, Oriental in munificence, and further bound the Germans to his service by an openhanded distribution of grants, privileges and dignities, which in truth cost him but little, since these petty potentates had long since seized the chance afforded them, by the perpetual disturbances in the Empire, to grasp at a certain amount of liberty for themselves.

A lesser man would now have proceeded to enjoy his triumph, so complete and so unexpected, in pleasure and ease; this might have naturally been Frederic's choice, for he had spent two toilsome years since he had left the delights of Sicily and he was by nature voluptuous and indolent; to one of his wide, alert mentality much of the active world about him must have appeared contemptible or ridiculous, and reading, mediation, the exercise of his gifts for music and poetry, the indulgence of his delight in beauty and grace, in refined and elegant diversions made a strong appeal indeed.

But Frederic Hohenstaufen looked beyond his personal gratification; he saw the world spread before him, struggling into some semblance of law and order, system forming out of chaos, Peace trembling on the heels of War, and he believed that he might make these things permanent, that, out of the confusion and darkness that had eclipsed Europe since the disruption of the Roman Empire, he might create an Empire as mighty, as united as that of the Caesars, but more secure as it would include the power and progress of those peoples, the Barbarians, who had overthrown the ancient power, and the influence of that new God that had overthrown the ancient gods.

No one could have conceived of a more lofty ambition, nor seen the task to his hand on a wider scale, and no one could have devoted himself to his work with greater single-mindedness, with a more profound wisdom.

Such men as Frederic are always accused of personal ambition; this is but the croaking of frogs in the marsh that follows the flight of the bird across the sky, the spiteful jealousy of the little souls that remain in the mud because they have no wings to fly.

It is not possible for a man of supreme intellect in a position of supreme power to feel the cringing humility of the mediocre mind with but little authority, or to doubt and depreciate himself as if he were a cloistered philosopher or an emasculate monk; such a man as Frederic Hohenstaufen faced even his God on equal terms, and if he saw the world like a jewel of silver and lapis lazuli hung at his belt for his adornment, he saw it in no spirit of petty arrogance, but with an ironic appreciation of his own supremacy in a crude, violent, ignorant age.

With deliberate abnegation of his own desires, he flashed through the dark forests, the heavy towns, the wide meadows of Germany, with his train of troubadours and dancers and scholars and glittering knights, a sparkling pageant under these cold skies, among this uncivilized, turbulent people, whose laws, customs and possessions were alike one rude confusion.

The fair, smiling Emperor held his Diet in city after city, travelled from castle to castle, received submission after submission from towns and feudal barons, administered swift justice, granted charters for the revival of trade and agriculture, threw the protection of his power over the weak, and hurled the wrath of his power against the oppressor; he was a despot whose will might never be questioned, but the reviving prosperity of the country, the gratitude of those he had protected and those he had enriched, the deep impression made by his personal charm and beauty and the bright splendour of his mind caused a universal admiration and applause to sound not only through the Empire but through the world.

Encouraged by these awestruck praises, Frederic proceeded to confirm the House of Hohenstaufen in Imperial power; he sent for his wife and little son, Henry, from Sicily, and, at the Diet of Frankfort in 1220, used all his influence to persuade the Electors to choose the latter, already Duke of Suabia and Ruler of Burgundy, as future King of Germany.

Frederic, by thus associating his son with him in the government and by securing to him the succession of the Empire, had achieved a personal triumph and openly flouted the Pope, whose main object was to prevent the aggrandizement of the Emperor and the Hohenstaufen.

This glittering success cost Frederic but little, so great was his prestige and popularity; he certainly gave his obedient Princes charters which were the first sanction of the disruption of the Empire, but this, like his former concessions, was but a confirmation of privileges long enjoyed and which it would have been dangerous if not impossible to rescind.

Frederic, besides this affront to the Papal authority, had further irritated Rome by his reluctance to fulfil the oath taken at his coronation in Aix-la-Chapelle; and this would have doubtless led to an open breach with Rome had not the fiery Innocent III died and been succeeded by a mild spirit, Honorius III, whose feeble protests were received by Frederic with courteous indifference, and specious excuses not untinged by irony.

The Emperor, having restored order and roused loyalty in Germany, soothed the Pope and secured a reversion of his dignities to his son, turned his attention to his Italian possessions, and in August, 1220, crossed the Alps again and descended into Lombardy at the head of a sumptuous cavalcade of Teutonic knights, such gorgeous and massive potentates as the Duke of Bavaria, the Margrave of Hohenburg, the Count Palatine, and the Archbishops of Mainz and Ravenna added to the imposing display of pomp and power that glorified Frederic Hohenstaufen, now at twenty-six years of age the foremost man in the world, and enjoying a popularity which was probably beyond that ever accorded to any other prince and which he had won by his own personal qualities, his justice, his affability, his prudence, his lively grace and dazzling accomplishments, his tolerant patronage of all types of intelligence and effort, his wide view of all questions of the moment.

While he had been consolidating his power in Germany, the great towns of North Italy had fallen into strife, the Guelfs revenging themselves on the Church that had protected the Ghibellines by seizing her property and expelling her prelates; Frederic glanced aside from this implacable confusion and proceeded to Rome, where he was splendidly crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in the gorgeous Basilica of St. Peter with all the pomp with which the Church dignified her most important ceremonies.

The blond and elegant Emperor, simply arrayed in spotless white amid a company resplendent with every device of worldly pageantry, received from the Holy Father the beautiful insignia of his stupendous office, the Cross, the Lance, the Sceptre, the Golden Apple, all symbols of various aspects of the power with which the Vicar of Christ invested his lieutenant.

Frederic did not receive these supreme honours without having to make some return for them; he paid homage to the Pope, he held his stirrup while he mounted for the procession through the city where the Emperor rode behind the Pontiff, he abased himself to kiss the jewelled slipper of Honorius, and, most important of all, he took the Cross from the hands of Cardinal Ugolino and repeated his vow of six years ago to lead a Crusade against the Infidel—adding on this occasion the promise to sail the following August.

Goodwill was now complete behind the two heads of Christendom, and Frederic, by no means dazzled by the glitter of the gem-encrusted Imperial diadem now added to his treasure chests, proceeded to engage in several weeks of laborious business; he issued many edicts to various cities, made many appointments, and sent out many manifestos to various provinces of his scattered realms; many of these were certainly concessions to Papal authority and measures of precautions against his enemies, the Guelfs, but with them were associated schemes of betterment for the general populace, protection for farmers, travellers and traders, and provisions against the robber and the rogue.

There is no reason whatever to doubt the sincerity of the Emperor in these decrees, or to suspect that they were merely the price of preferment received; it was natural for him to associate Christianity with law, order and progress, and to regard the Papal authority as the main support and hope of the future peace and enlightenment he had himself so much at heart, and the stern laws he promulgated against heretics must have seemed to him necessary curbs on the rebellious and the lawless. But a cloud was soon to arise between Emperor and Pope.

Frederic proceeded to his beloved Sicily and found there confusion likely in a Kingdom left too long without a King; in restoring his authority and punishing the refractory he showed a sterner haughtiness than he had yet disclosed, and among those whom he deprived of ill-gotten honours or dubiously gained estates were several priests and churches.

The immediate remonstrance of Honorius was received impatiently by Frederic, who declared, without a trace of the submission that he had shown in Rome, "that I would rather lay down my Crown than lessen my authority." He repudiated the compact between his helpless mother and the unscrupulous Innocent III and proceeded to exert the ancient privileges of the Sicilian Kings.

With sharp justice and a cold and implacable severity he put down his rebellious subjects, then led a force against the Saracens still lodged in the Western mountains of the Island, signally defeated them, hanged their leader, and transported twenty thousand of their finest fighting men to Apulia, where he ejected the Christians from Lucera and established the Moslems in their place, allowing them to use the Cathedral as a Mosque: these Saracens were to serve as a colony of warriors for the defence of the Empire.

This action revealed to the Papal power the manner of man they had to deal with; for this superb piece of bold statesmanship whereby rebels were turned into loyal soldiers (of the finest type of fighting men) was conceived and executed with a haughty defiance of Church, tradition and public opinion hitherto unknown.

The character of Frederic had developed since his first coronation; his expanding genius was no longer to be curbed by convention, nor hampered by the fears, doubts and restrictions that control small minds; in the growing maturity of his powers he became intolerant of all restraints, impatient of any superior authority, he revealed that he was fierce, bold, cruel and superb as a beast of prey beneath his smiling amiability, his gracious charm, his ready tact, and as self-assured and indomitable as one must be who looks abroad and sees no equal. No one, since the Church had been established in Europe, had flung such an affront in her face as Frederic had now done in this Saracen colony, established at the expense of Christians.

A superstitious age was profoundly shocked, and even the mild Honorius was moved to an indignant protest.

Frederic replied with that ironic contempt for an opponent which is generally accounted as duplicity; he said that, Moslems being of no account in comparison with Christians, it was better that they should be employed in the dangerous occupation of War.

Honorius must have noted the fallacy of this answer and the arrogance that prompted it, he must have realized the immense power this Moslem army, not amenable to the usual threat of excommunication, gave to the Emperor, and the menace to Papal prestige that such an action and such an excuse concealed; but he gave way, out of the weariness of old age and the timidity of a gentle nature, and renewed his plaintive efforts to induce the Emperor to undertake the crusade to which he had twice pledged himself with all solemnity.

The crusades were, in every way, to the advantage of the Popes; not only were they excellent demonstrations of the might, loyalty and religious zeal of the Christian Princes, not only did they provoke outbursts of hysterical enthusiasm for the Church, but they exhausted those resources which might have been turned against the Papacy, and involved the Kings and warriors of Europe in warfares with the Infidel and with each other that allowed them no leisure to question Papal supremacy, or to resist Papal encroachments.

But Frederic had no mind to weaken himself in this way, no animus against the Saracens, and no vivid enthusiasm for Christianity; he visualized an Empire united under a rule of tolerance where all sects, races and creeds might work together for a common splendour of progress.

No doubt his first oath was sincere, if the second was forced, but it was the oath of a boy of twenty given at a moment of unparalleled success, and, as Frederic developed, the Crusades must have appeared to him as fantastic and boyish adventures unfitted for a man of genius. He did not love fighting and hardship as warriors like Richard Coeur de Lion had loved them, exploits of personal bravery had no attraction for him, though he was absolutely fearless; he was too subtle, too fine for crude and aimless exploits.

Like Robert the Bruce after Bannockburn, he looked abroad on his own realms and saw that much needed doing there before any fanciful expeditions in the East could be undertaken; but, unlike the Scottish King, he relinquished the fulfilment of his oath without any passionate regret or any deep remorse.

He, however, sent an almost constant supply of soldiers to the East, and sumptuously entertained in his profane Sicilian Court all warriors of the Cross and pious pilgrims journeying to and from Jerusalem.

In the year 1222 he ordered a fleet of forty galleys to the support of the Christians under King John of Jerusalem, who had just made the notable conquest of Damietta.

Unfortunately for the Emperor, his galleys arrived only in time to see the city retaken by the Infidel and to learn that the triumphant Sultan had imposed a truce of eight years upon King John, softening this by a gracious present of a portion of the true Cross.

The whole of Europe was darkened by the shadow of this humiliation, and the gentle Honorius was inspired to threaten Frederic with excommunication if he did not undertake in person the task of reviving the prestige of Christendom.

Frederic was, however, little moved, he continued to occupy himself with his own affairs, and, at two meetings held with the Pope, at Veroli and Fiorentino, he induced the aged Pontiff to agree to further delays.

On these occasions Frederic met John, Crusader King of Jerusalem, and betrothed himself to this old warrior's daughter Yolande, the Spanish Empress having died the previous year; Yolande was heiress to the crown of Jerusalem, so Frederic had now a personal interest in the prospect of a crusade.

This, however, seemed no nearer than before; not only Frederic but Europe listened coldly to the Papal expostulations and exhortations; neither England, France, Italy nor Germany could be roused to the old reckless excitement, and Cardinal Ugolino, who had handed the Cross to Frederic when he took his second oath, endeavoured in vain to rouse Lombardy to enthusiasm.

The Pope was not to be easily thwarted in a matter so nearly touching his own interests, and he pestered Frederic until the Emperor agreed to sail in August, 1227, and to maintain a thousand knights in Palestine for two years; the Pope asked, this time, for a guarantee for the fulfilment of this oath, and Frederic agreed to pay, in instalments, 100,000 ounces of gold to the King and Patriarch of Jerusalem; not only was he to forfeit this if he failed to go to the East, but he was also to be instantly excommunicated.

It is probable that Frederic would not have agreed to these hard terms had he not now been married to Yolande, heiress of Jerusalem, which caused him to look on the crusades from another angle, that of his own glory.

While the Pope thought he had bound the Emperor to his service, the Emperor was resolving to use this expedition to gain yet another Kingdom for himself and perhaps indulging the daring dream of adding the Empire of the East to the Empire of the West.

His first move in this direction was to deprive his father-in-law of his kingly rank, which the doughty Crusader only held in virtue of his marriage with the Queen of Jerusalem, and which legally reverted to Frederic; John de Brienne was furious at this treatment but was unable to resist, and the Emperor now added to his mighty honours that mystical unsubstantial title, King of Jerusalem.

Frederic, having now quieted both his Germanic and his Italian possessions, disposed of the internal menace of the Saracens in Sicily, reduced the pretensions of the Church in his native country, and, with bold, pitiless hands, crushed his enemies and restored a fair measure of prosperity and tranquillity to these portions of his scattered dominions, and decided seriously to prepare for an expedition to the East.

He went North, at Cremona summoned a Diet and called on the Italian chivalry to meet him with the object of preparing for the long discussed Crusade.

At the same time he summoned the boy Henry, his son, who was maintaining the Imperial authority beyond the Alps, to bring the German knights to assist in the Holy Expedition.

Lombardy was, however, entirely Guelf in sympathy and replied to the Hohenstaufen commands with insults and menaces; Milan revived the Lombard League which had been first formed against Barbarossa, Verona barred the way to King Henry so that he was forced to return to Germany, and all the great cities, Piacenza, Verona, Brescia, Faenza, Mantua, combined to ruin the purpose of the Diet of Cremona and to force Frederic, who was unaccompanied by an army, to retire South.

The Ban of the Empire and the Ban of the Pope were hurled alike at rebellious Lombardy, but with poor results; the utmost threats could only induce the haughty and powerful cities to assist the Ghibelline Emperor to the extent of four hundred knights.

In the March of the year (1227) triat Frederic was pledged to start for the East, Honorius III died, and the fierce and enthusiastic Cardinal Ugolino was elected in his place under the name of Gregory IX.

The struggle between Pope and Emperor, which had been so intermittent and courteous between Frederic and Honorius, now began in good earnest between Frederic and Gregory.

The tolerant Emperor had always admired the vast erudition, the rigid asceticism, the brilliant eloquence of Cardinal Ugolino, but Cardinal Ugolino had always detested the worldly, voluptuous and liberal Emperor, and his first act of Papal authority showed the leaping out of a long held spite against Frederic.

As he could say nothing on the question of the Crusade for which Frederic was preparing with all speed, the grim old man of eighty, soured by rigid monastic discipline, and without any of the softer human passions or the more lovable human failings, administered a sharp rebuke as to the private life of the young, splendid and virile Emperor.

Frederic received this reprimand about his "earthly lusts" with an indifference that appeared submission, his ironic smile gave the measure of his appreciation of the gloomy and ferocious old ascetic, and he continued his preparations for the long deferred Crusade which Gregory was already viewing with a hostile eye.

This Crusade was disastrous from the first, none of the monarchs of Europe offered any assistance whatever, and even Frederic's immediate vassals were reluctant; the Duke of Austria refused his support, and the Landgrave of Thuringia had to be heavily bribed; in truth, the expedition was unpopular with every one save the priests.

By August, however, the Germans were embarking at Brindisi for Acre in a heat so violent that the armour was melted on the knights' backs and brows; the Northerners, unused to such a torrid climate, succumbed by hundreds to fatigue and fever in the Southern port.

When Frederic arrived at Brindisi, he was himself ill; his delicate but vigorous body, his superb health had given way under unexampled strain and vexation; the journey under the blazing skies, over the dry roads of an Italian summer, the continual vexations, irritations and disappointments of his enterprise, had brought him to the verge of collapse; his doctors advised him to abandon the expedition till the autumn.

But Frederic decided to persist in his resolution, not from any desire to placate the new Pope, but because he was not easily to be turned aside from anything he had undertaken.

The Christian hosts were ravaged by sickness, several of the leaders were too stricken to leave Brindisi, but Frederic sailed. After a few days at sea he became so seriously ill that his galley was forced to return to Italy; the forty thousand Christians who had already reached Acre returned when they heard that the Emperor was not coming, and the long promised Crusade came to a disastrous conclusion.

Frederic, slowly recovering from his nervous fever at Naples, sent formal explanations of his failure to the Pope; but Gregory, against reason, prudence or justice, at once excommunicated the Emperor, with all the terrors of Book, Candle and Bell, and with all the zest of one who seizes a coveted opportunity to injure an enemy.

Gregory's ferocious action, followed as it was by a furious diatribe against Frederic, full of bitter invective and misrepresentation, addressed to the clergy, made an immediate and deadly breach between Empire and Papacy and brought into the conflict between these two powers the hideous element of personal hatred and jealousy.

If it must be admitted that the pretensions of the earlier Popes had much justification in the services the Church had rendered to civilization, then struggling from tribal to national status, in being a central authority and a powerful control, it cannot be conceded that Gregory in treating a man like Frederic as an enemy, and in endeavouring to crush a Prince so splendid, so popular and so enlightened, showed the least spark of statesmanship or foresightedness, of prudence or caution; his actions appear indeed to have been inspired by a jealous spite, a petty censoriousness and by that half-crazed arrogance too often characteristic of the occupants of the Chair of St. Peter and which seems to show that the claim of Divine Authority is too apt to turn the brain of a mortal man.

Frederic was probably expecting the eternal curses of the Pope and received them with his ironic and indifferent smile; he ordered the clergy in his dominions to ignore the excommunication (a command they obeyed) and answered the abusive manifesto of the Pope by another which he dispatched to all the monarchs of Europe.

In the letter he sent to the feeble son of the dastard John, Henry III of England, he made a dauntless and superb attack on the Power of Rome which showed him to be as bold as he was clear-sighted:

"Such is the way of Rome; under words as smooth as oil and honey lies the rapacious blood-sucker; the Church of Rome is like a leech...the whole world pays tribute to the avarice of Rome...the primitive Church, founded on poverty and simplicity, brought forth numberless Saints; she rested on no foundation but that laid down by Our Lord Jesus Christ; Rome is now rolling in Wealth...Remember that when your neighbour's wall is on fire, your own property is at stake."

Frederic followed this vigorous appeal to the rulers of Europe by prompt action against Gregory. He summoned the most powerful families of Rome to his Court, bought their estates from them at their own price, and returned them as fiefs; he was already so popular in his enemy's stronghold that the people broke into St. Peter's when Gregory was celebrating Mass, and showed themselves such warm Ghibellines that the Pope was compelled to flee to Perugia.

From this retreat the terrible old man hurled further fulminations at the Emperor, forbidding him to undertake the Crusade while under the curse of the Church, but Frederic continued his preparations and sailed from Otranto on 29th June, 1228, with a train of only a hundred knights, for his treasury was nearly empty and the Crusade as unpopular as ever in Europe.

In the spring of that year his girl Empress, Yolande, had died, leaving a son, Conrad, and Frederic considered himself heir to her crown of Jerusalem.

In September he arrived in Acre, leaving the world amazed at the courage with which he ignored the excommunication, affronted the Christian Church, and denied the infallibility of the Pope.

A large and motley force of Christians were assembled at Acre to welcome him, the Templars and Hospitallers, the Teutonic Order, founded by his grandfather, Barbarossa, and a fair number of Lombards, Germans, French and English.

Gregory, however, by furious spite blinded to the common good, sent two Minorite friars into the Emperor's Camp with the threat of excommunication against all those who dared to follow the Eagles; this split Frederic's forces in half, the Templars, Hospitallers and many others refusing to follow one cursed by the Church; his tact and popularity, however, brought these round to a reluctant submission, and the Teutonic knights, under the famous Hermann von Salza, remained unwaveringly loyal.

Frederic marched to Jaffa with this disunited force, and there displayed his genius by one of those actions with which he continually amazed, shocked and awed Europe.

He had long been on friendly terms with the leader of the Saracens, Sultan Kamel, and from Acre had sent him lavish offerings, a compliment returned by the gift of a camel and an elephant; emissaries went to and from the camps of these two philosophical Princes, exchanging mathematical problems and philosophical disquisitions; to the further scandal of the outraged fanatics who murmured in his train, Frederic received from Kamel a bevy of Eastern dancing girls who amused his brief leisure with their soft voices and languorous poses.

Feeling ran so high against Frederic that the Templars actually apprised the Sultan of a solitary expedition the Emperor proposed to take, to bathe in the waters of the Jordan, with the suggestion that this would be an excellent opportunity for the assassination of the excommunicated Crusader.

The Sultan, however, sent the traitors' letters to Frederic, who at the same time had intercepted one from the Pope to Kamel, urging the latter to have no dealings with the Emperor.

Thus hampered, weakened, affronted and threatened on every side, not able to count on the loyalty of any but his Teutonic knights, and at the end of his money, Frederic was obliged to lower the first demands he had made on behalf of Christendom and to accept the best terms he could wring from an opponent fully conscious of his difficulties.

That these terms were as good as they were was a high tribute to the genius of the harassed Emperor; by the nine articles of the Ten Years' Truce he signed, February, 1229, he obtained more than any Crusader had obtained since 1099 when Jerusalem was first captured; the Holy City was now returned to Christendom, and most of the articles were concessions from the Sultan to the Emperor.

This bloodless success of the sixth Crusade was entirely owing to the genius of Frederic; single-handed and in face of most exasperating difficulties he had achieved, by sheer force of character and intellect, more solid advantages for Christians than the flamboyant exploits of generations of Kings had been able to accomplish.

It is obvious that had he been supported by the Pope his success would have been overwhelming; such as it was it remained an amazing proof of his high qualities of statesmanship and the charm of his subtle personality which had a peculiar fascination for the Oriental mind; for the first time the Moslem met a cultured and tolerant Christian and also for the last, for though Louis IX was a courteous saint he was also a fanatic.

This treaty, so greatly to the advantage of the Syrian Christians, was received by the Papacy with a howl of fury, and Gerold the Patriarch of Jerusalem, the Papal Legate, was instructed to thwart and oppose Frederic in every way possible, while a Papal army marched into Apulia under Frederic's father-in-law, John de Brienne, and the Banner of the Keys was raised as a rallying point for all the malcontents of the Empire.

Frederic heard this news without surprise, nor did it send him hot haste home; he probably saw that a Christian Kingdom in Syria was a chimerical vision, and that the days of the Crusades were over, as indeed they proved to be, for, despite the impetuous piety of Louis IX, these wasteful invasions of the East only dragged on for another half century.

But Frederic wished to be crowned in Jerusalem, his own Kingdom, and hither he repaired, the fanatic Gerold at his heels, repeating the Ban on every available occasion and finally laying the Holy City itself under an Interdict during the accursed Emperor's presence there.

The superb Frederic, however, crowned himself with his own hands in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, surrounded by his loyal Teutonic knights, and during his short stay in Jerusalem showed himself not only tolerant but favourable towards the Saracens; he forbade a Christian priest to enter the Mosque of Omar, he ordered the Muezzin, silenced out of deference to him, to sound again, and when he saw the gratings over the windows of the Holy Chapel he remarked, with his serene irony:

"Ye may keep out the birds, but how shall ye keep out the swine?"

He proceeded, immediately after his last coronation, to Acre, where his conduct gave further cause for scandal to the faithful Papists; while he was amusing himself with Eastern culture and Eastern luxuries, he kept the odious Gerold prisoner in his own house, filled the churches with German archers, and caused rabid friars who had insulted him to be flogged.

Then, denouncing the mean and short-sighted treachery of Gerold and the Templars, the Emperor, still preserving his disdainful patience, dismissed the Crusaders and sailed from Acre, followed by the curses of the priests whose Faith he had come to uphold and whose Founder's Tomb he had restored to Christian care.

With the arrival of Frederic in Brindisi in June, 1230, the rebellion seething in his Kingdoms collapsed, town after town fell to his victorious onslaughts, and by end of the next month the confounded Pope, who had but few sympathizers in his own country and none in Europe, was compelled to sue for peace.

A treaty was signed at San Germano, a meeting took place at Agnani, the excommunicated Crusader was, perforce, received into the reluctant bosom of the chastised Church, and the bitter old Pope retired to brood over his supreme humiliation, while the victorious Emperor took up the task for which he was so eminently fitted, the peaceful governance of a great nation.

Frederic, in his thirty-fifth year, four times crowned, was at the climax of his magnificence, the triumphant ruler over wider dominions than any man was ever to unite under one standard again until the age of arbitrary rulers was long past; he governed in reality that vast realm which the latter Emperors, those shadowy Hapsburg Caesars, governed in pretence, and was in truth the Emperor of the West, a dignity claimed for centuries to come, but never effectively enforced nor mightily maintained.

Never again was the throne of Carolus Magnus to be occupied by one who filled it with such spacious dignity, never again was the confused heritage of the Caesars to be held together by a man of such superb genius and such grandeur of character.

Frederic remains not an Emperor, but the Emperor, the only Prince of a long succession of Princes who was able even slightly to justify the supreme arrogance of the claim of universal dominion.

The gloomy landscapes, dark cities, sombre skies and rude inhabitants of the North Frederic had never loved, and he now held his gorgeous Court in Sicily or Apulia among those soft scenes and in that delicious climate in which he had passed his youth.

While he remodelled the tangled confusion of the legal system of Southern Italy with the insight and vigour of a Justinian, founded the University of Naples, put down the heretic and the evil-doer with cold severity, encouraged learning, the arts and commerce with prodigal generosity, permitted a wide tolerance to the profession of all creeds, Frederic's genius found personal expression in the cultivation of science, poetry and architecture, in the formation of a society sparkling with a brighter lustre of culture than Europe was to see till the Renaissance, in the active delights of the chase and hawking, in the voluptuous delights of sumptuous relaxations of feasts and entertainments with his poets, his dancers, his acrobats and magicians.

There was no subject open to human knowledge or occurring to human curiosity that the mighty mind of the Emperor did not invade; no living man could compete with him in learning, his accomplishments, like his character, were beyond the comprehension if not the wonder of his times.

In philosophy, mathematics, languages, medicine and natural science, Frederic could confound the learned men even of the learned East, he was a soft and fluent poet, a speaker and writer of forcible eloquence, a great builder both of dark forts and airy villas.

Exquisite palaces of marble and alabaster, mosaic and sculpture adorned, rose above the flowers and groves of Sicily and Apulia, grimmer castles were erected in the disloyal North; Frederic's influence began to change the whole aspect of the age, to bring about a revival of law and order, of learning and the arts, of trade and prosperity, of ease and luxury, hitherto unguessed at by his contemporaries.

As he was "Lord of the Earth" so his Court was one of the marvels of the Earth and became the nucleus of progress and the seat of all achievements of intellect and all the allurements of beauty and grace. With his astrologers he peered into other worlds, with his troubadours, conjurors and wits he relished this world, with scholars he discussed the past and with magicians the future; galloping over the delicious plains of Apulia with his blindfolded hunting cheetahs riding beside him or with his bright glittering Emperor's hawk, the Golden Eagle, on his delicate wrist, from one hunting lodge to another (palaces of delicate pleasure, all of them), seated on his pearl-strewn throne in the Imperial purple, receiving embassies or guests with noble courtesy, wandering through his exotic menagerie where Eastern slaves tended animals monstrous and fantastic to the Western eye, the figure of Frederic was ever surrounded by a blaze of admiration even greater than his material glories.

His mighty power now seemed secure, and the Sicilian Caesar, in the prime of life with two sons to succeed him, might with confidence believe that he had reared an Empire as permanent as magnificent and one that would continue to increase in prosperity and enlightenment under the Hohenstaufen Dynasty. His spacious statesmanship had laid secure foundations for such a future; all his measures were prudent, wise, far seeing; he only made one mistake; he underestimated the influence and the hatred of that old, old man in Rome; he believed that he had broken the monstrous tyranny of the Popes which had become not the rule of Christ, but the rule of Lucifer; his own lofty and liberal mind failed to gauge the strength of the hold of crude and stupid superstitions on the rude peoples of the moment; surrounded by all that was enlightened and tolerant, imbibing the placid philosophies of the East, with a wide knowledge of the various creeds that have in turn dominated mankind, Frederic, in the free soft airs of Apulia, in all the brilliant freedom of his Court, could not estimate the evil power possessed by the Pope he had subdued but not conciliated, nor the black menace that lay in Gregory's brooding silence.

From his point of view the Pontiff had cause enough for a sense of bitter outrage; not only had the Emperor's new code summarily disposed of many clerical privileges and pretensions, not only had theology been replaced by the liberal sciences in the Curriculum of the University of Naples, but Frederic's whole existence was an example of what was, in Gregory's eyes, paganism or atheism.

Frederic was, in fact, using all his genius, his charm, his immense popularity and influence, in the support of free thought and the intellectual investigation of those manifold problems that the Church had regarded as her own exclusive province or banned as black magic; Gregory was not wrong, as latter ages were to show, in fearing that such a liberal mind as that of the great Emperor was fatal to the pretensions of the Papacy.

Nor did Frederic disguise his attitude; not only did he bestow his favours impartially on those of all creeds, but he openly made ironic comments on the dogma of the Christian Church.

Passing through a field of ripening corn he asked, with his satirical smile:

"How many gods will be made of that? How long will that mummery last?"

And he had been heard to argue that if the founders of religions, such as Jesus and Mahomet, were not impostors, their followers made them appear so; these tales and worse were brought to Gregory.

The Emperor's dearest friend and most trusted counsellor, Pietro da Vinea, was of like mind, and those others whose advice he sometimes sought, and to whose debates he earnestly listened, were of that wisdom that is shackled by no formulae nor creeds.

Frederic had built model farms, planted corn and vines on waste places, sent merchant ships to Egypt and Syria, instructed his people in peaceful arts, shown them an example of culture and elegance, protected and encouraged them on the long road from chaos to prosperity—but what was all this in the eyes of Gregory IX?

Frederic had founded no churches, raised no monasteries, poured no wealth into the lap of Mother Church, there was no bigoted priest among his counsellors, he paid but a light ironic lip service to the Christianity of which he was the secular head.

Nor was his private life modelled on the Christian ideal; on the score of licentiousness the Church could have had but little to say, since this was the favourite vice of her own clergy, and, if Gregory was himself an ascetic, this was due more to a frozen nature, a gloomy disposition and extreme old age, than any rigid standard of morals among the priesthood, and, had Frederic been a dutiful son of the Church, he might, like many a Christian monarch before and after him, have indulged unreproved, nay even approved, in any illicit or scandalous intrigue that pleased him; but his morals received some of the wrath aroused by his atheism.

Frederic was not vicious; he was far too fastidious, too cultured, too intellectual to find any attraction in coarse indulgences of the senses; though such a sumptuous provider of feasts himself, he was sparing in his food and most temperate in his drink, nor did his festivals and banquets ever degenerate into orgies and displays of mere licence and profligacy; had such been the case he could not have retained his immense hold on the minds of men, nor his own vast intellectual supremacy.

He kept a harem at Lucera, his Saracen city, guarded by black eunuchs, where dwelt jealously secluded Eastern and Western beauties, and since the death of his second Empress, he had installed in her place a Milanese lady, Bianca da Lancia, who, strictly enclosed in Oriental privacy and grandeur, might be regarded as his Sultana; there was neither vice nor immorality in this; Frederic was merely following a different and, it may be added, a more elegant custom than that employed by Western potentates whose crude amours were often coarse enough.

Nor was there any mischief in, nor rising out of, this Oriental system about which there was neither hypocrisy nor concealment. Frederic never interfered with the wives or daughters or mistresses of his subjects (such a common cause of disorder and tragedy in mediaeval Europe), nor did he bring his name into the odium and disgrace of any scandalous or devastating passion; he preserved always the strength and dignity of a man never influenced by women, though he set the example of an exceeding courtesy towards them, and many of his laws were in their favour.

For the rest it may be doubted whether feminine seductions occupied more of Frederic's attention than that of any other Prince of Southern temperament, Eastern training and unlimited opportunity for selfindulgence, and the exaggerated tales of his extreme licentiousness which have been so dwelt on really prove nothing but the distorted spite of his enemies.

Frederic saw no reason why he should follow the Christian ideal that Christians themselves found far too difficult to achieve, and, in choosing the customs of the East, could hardly suppose he was affronting the purity of a Church whose corruptions were so manifest and whose licence was so universal.

Frederic must have heard the denunciations of the clergy against his charming odalisques with more than his usual amused irony; the man who had abolished serfdom and been the first monarch to summon the third estate to his councils must have laughed indeed at the fierce importance given to his private relaxations which were adorned by all that was lovely and delicate.

It is said that St. Francis of Assisi visited the languorous Sicilian Court of Frederic; a strange meeting this, between the man who was the literal follower of Jesus of Nazareth and the man who opposed the monstrous worldly power usurped in that Gentle Name.

They must have gazed at each other with a deep curiosity, the dirty, sickly, ragged monk, the perfumed, exquisite and voluptuous Emperor, made delightful with every worldly device, charming with every grace of mind and body.

It is interesting to wonder if the omnipotent Prince saw in his wretched guest that mystic and holy light that was to make the name of Francis of Assisi reverenced by multitudes when that of Frederic Hohenstaufen would be forgotten save by the learned.

It is certain that he listened with courtesy to the sweet doctrines of the Mendicant monk, which were as in advance of the times as his own wide tolerance, and which were not so different from those he was familiar with from the withered lips of Eastern anchorites.

Renunciation, Abnegation, Poverty and Self-sacrifice, these virtues were impossible to the rich character, the active powerful mind of the Emperor, but he could respect their pale glory; there is little doubt but that the cult of St. Francis would have flourished unchecked in the Empire this tolerant King hoped to establish; and Frederic, watching the mean figure of the miserable monk, whose haggard face was transfigured by Divine tenderness, cross his alabaster halls and descend his gilded steps, pass his scarlet-clad Ethiopians and disappear under the plumy trees of his delicious gardens, must have felt as another ruler felt when faced with another such figure—"What is truth?"

The first hint of the dark doom that was to overwhelm for ever the brilliant promise of the Hohenstaufen Empire came from within Frederic's own family; his son Henry, installed as regent ruler of Germany, joined the Lombard League, in a rebellion against the Imperial authority which the Emperor had little difficulty in crushing; the feeble, ungrateful and profligate Henry, once pardoned in vain, was at last shut away a prisoner in one of the Apulian castles.

When this disorder was effectually repressed, Frederic, then in Germany, married for the third time, Isabella, sister of Henry III of England; the beautiful Angevin Princess delighted the fine taste of Frederic, but there were those who considered the marriage beneath him, England being, technically, a mere fief of the Empire.

Frederic followed the gorgeous ceremonial of his marriage by a resplendent Diet at Mainz, where even the son of the Guelf Emperor, Otto of Brunswick, a cousin of the Empress, swore submission to the Hohenstaufen.

This Diet was the most impressive manifestation of his glory Frederic had yet made; never again was any emperor to appear in such a dazzle of pomp, with such a blazing reputation, as the acknowledged head of so many nations.

This glittering display of armed might and farreaching power also contained the germ of that struggle which was to bring all the grandeur of the Hohenstaufen to the bloody dust.

Frederic resolved to chastise the miscreant and disloyal Duke of Austria and to punish the sullen disaffection of the great cities of Northern Italy.

At first the punitive expedition that Frederic led against the Guelf was of a flashing success that further increased his almost incredible fame and power; the great battle of Cortenuova was a carnage of his enemies; he rode like a Caesar indeed into Cremona, followed by his monstrous elephant dragging the Carroccio, the cherished symbol of Milan, on which the captured podesta was bound like a slave.

At Lodi he gathered together vassals and allies from all corners of the earth; there were reinforcements from Sultan Kamel, from Vataces, Emperor of the East, from France, Spain and Henry of England, whose sister the Empress was now the mother of Frederic's third son, the second Henry.

All the coffers of the world seemed open to pour their treasures at the feet of Frederic, all the men-atarms of East and West were eager to do homage to the lord of the world and to serve under the conquering eagles, there was no limit to Frederic's glory and might. Nor any limit to his revenge.

Milan sued for peace in vain, uselessly made the most humiliating concessions; Frederic was not to be deprived of his glut of vengeance against this ancient gadfly of his House; he had shown himself clement and just in peace, but in war terrible with the cold, ferocious cruelty of the Hohenstaufen; Eccelin da Romano, a man spoken of, even in those fierce days, as an incarnation of the Devil, was his trusted lieutenant, and he never checked the atrocities of his Saracen soldiers nor restrained the savagery of his Eastern allies.

Horror and darkness reigned in Lombardy, in Milan Cathedral the derided Crucifix was hung upside down by a people driven to a lust of despair.

The coming of the terrific Emperor with his hideous negroes, his grotesque beasts, his Eastern Magi, his troops of jewel-hung wantons, his escorts of blood drenched warriors had been like the opening of Hell's mouth belching forth demons on to the lovely plains of Lombardy.

The figure of Frederic Hohenstaufen himself, implacable, charming, superb, with his amazing learning, his Oriental customs, his still cruelty, his swift movements from town to town, his known atheism, seemed to the excited minds of the despairing rebels that of Lucifer, the fallen angel, more potent for evil than God was potent for good.

And many saw, in the elegant knight clad in the light armour, with the imposing Imperial Crown encircling the peacock plumed helmet that rested on the reddish hair, in the shaven face with the small nose and full lips, in the pale bright ironic eyes, the dreadful personification of Antichrist.

Five desperate cities still held out against the Imperial wrath; Frederic had made the first definite their own concessions nor the clemency of the Hohenstaufen, proceeded to defend herself with that fury of desperation that is so often successful.

Frederic and all his dreadful panoply of war was unable to take Brescia; after two months of bloody struggle he was obliged to raise the siege.

A conqueror's first check is dangerous to his fame; Lombardy saw that the Emperor was not invincible and redoubled her frantic and ferocious resistance; and, while the Guelfs were rallying in this brief breathing space, Frederic made another error, even more fatal to himself than that of his injudicious vengeance against the Lombards.

He married his natural son, the beautiful Enzio of the long gold locks, to Adelasia, widow of the King of Sardinia, and haughtily claimed the island, then a Papal fief, as lost territory of the Empire.

This was a definite challenge to the Pope, one that Gregory was quick to seize and that Frederic would have been wise not to make. The long contained, bitter hate of the old man in Rome had at last found occasion to break forth in hissing rage.

There is something gigantic and grand in the wrath with which the aged Pontiff, then nearly a hundred years old, met the arrogance of the loathed Prince, and once again hurled anathema against his mighty rival for universal power.

On Palm Sunday, 1239, Frederic Hohenstaufen was again excommunicated with all the dramatic ritual of the outraged Church.

The Emperor, holding sumptuous Court at Pavia, received the news with sardonic indifference; Europe was distracted by the various cartels and manifestos issued first by the Pope and then by the Emperor, in which each stated his case with glowing eloquence and selections from the lurid denunciations of the Apocalypse; Frederic's main accusation against Gregory was that of avarice; that of Gregory against Frederic, atheism.

In this warfare of polemics Frederic might have been considered the victor; the Princes of Europe were not to be roused against him. Louis IX declared himself his partisan, and England, when further squeezed to provide funds for the Papal coffers, declared roundly, "the greedy avarice of Rome has exhausted the English Church." Germany was wholeheartedly for Frederic, the Archbishop of Salzburg plainly named Gregory Antichrist and it seemed that the fulminations of the Pope would rebound against himself.

Doubtless at that moment it seemed to Frederic that he would be able to achieve the mighty purpose unfolded in his final proclamation to his Princes:

"I am no enemy of the priesthood; I honour the humblest priest, as a father, if he will keep out of secular affairs. The Pope cries out that I would root out Christianity with force and by the sword. Folly!—as if the Kingdom of God could be rooted out by force and the sword; it is by evil lusts, by avarice and rapacity, that it is weakened, polluted, corrupted...I will give back to the sheep their shepherd, to the people their bishop, to the world its spiritual father. I will tear the mask from the face of this wolfish tyrant, and force him to lay aside worldly affairs and earthly pomp and treat in the Holy footsteps of Christ."

The mighty old Pope was an adversary worthy of Frederic; he declared a Holy War against the Emperor and gave the Guelf faction in Lombardy the immense stimulus of his support; the enemies of the Hohenstaufens were permitted to consider themselves as Crusaders and to wear the Cross on their arms; Papal Legates everywhere animated the rebels, and Frederic's next campaign against Milan proved abortive; he could not take the great city that shortly before had offered in vain to burn her banners at his feet.

His son Enzio had, however, made a victorious progress in the March, and Frederic, turning towards the Papal dominions, entered the open gates of city after city which pulled down the standard of the Keys to raise that of the Eagles.

In the very streets of crowded Rome the volatile people shouted for Frederic the conqueror, and the Pope was in danger of being sacrificed on his own altars.

But the indomitable old man saved himself and his cause by an action of flamboyant courage; unarmed, in full glitter of holy vestments, surrounded by the sweet faces of little acolytes and the shrunken visages of ancient priests, Gregory IX tottered forth from the Laterano and proceeded on foot through the narrow streets of Rome close packed with a hostile populace yelling for Frederic Hohenstaufen the bright and mighty Caesar, the smiling and superb conqueror.

Before him were borne aloft the most sacred relics of the Holy City, the heads of St. Peter and St. Paul and a fragment of the True Cross.

The feeble old man staked everything on this magnificent gesture and won.

Rome, in a revulsion of feeling, was soon cringing at his feet, and Frederic lost all chance of a welcome in the Holy City.

A desultory warfare, confused and bitter, marked by treachery, cruelty and rapine on either side, now dragged on; Frederic showed a noble clemency to the heroic little garrison of Faenza and Benevento which stands out among the atrocious episodes of this ghastly struggle as worthy of record: Frederic was not often merciful.

In the midst of this unnatural war between the two heads of Christendom, Europe shuddered to hear that a million and a half ferocious Tartars were hurling themselves into Hungary, sweeping the Magyars before them; Gregory did not hesitate to accuse Frederic of inviting the Pagan hordes to devastate Europe.

The Emperor scorned a reply to this crazy malice and sent his sons, Enzio and Conrad, against the "opposing Devils" as he called them, and issued one of his grandiose summons "to every noble and renowned country lying under the Star of the West" to help defeat the barbarians whom "Satan himself has lured hither to die before the Victorious Eagles of Imperial Europe."

The response to his eloquent appeal was poor, and it was left to the chivalry of Germany to turn back the tide of Tartar invasion into the unknown regions of Asia whence they came.

Meanwhile the inexorable Pope, defeated on every hand, summoned a General Council of the Christian hierarchy with the avowed object of deposing Frederic.

The Emperor not only refused to submit to such a tribunal, but his allies, the Pisans, captured the Genoese fleet that was bearing the bulk of the Prelates to the Conclave; these priests, by Enzio's orders, were chained and cast into miserable prisons where, in wretchedness and disease, they had dismal leisure to repent their folly in obeying the Papal mandate.

Frederic now advanced on Rome and captured the town of Monteforte; this last loss was too much for even the iron-hearted Pope, still breathing fury against his enemy, his implacable spirit left his exhausted body in the hot summer of 1242; he had been dauntless to the last and shown a blaze of courage that would have been wholly admirable if it had not been inspired by a blaze of hate.

"He is dead," said Frederic serenely, "through whom Peace was banished from the Earth and Discord prospered."

But he had left heirs.