Amazon - Website

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: There and Back: The Story of an Australian Soldier 1915-35 Author: Rowland Edward Lording, writing as A. Tiveychoc * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1600501h.html Language: English Date first posted: March 2016 Most recent update: March 2016 This eBook was produced by: Colin Choat Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

With Forewords by

L A. ROBB, C.M.G., State President, R.S.S.I.L.A., N.S.W.

and

"AN UNKNOWN SOLDIER"

Published in 1935 by

Returned Sailors And Soldiers'

Imperial League Of Australia

New South Wales Branch

Go to Table of Contents

TO

MRS O. E. H. B.

ONE OF THOSE GLORIOUSLY UNSELFISH AND LOVING WOMEN OF THE WAR

WHO

BROUGHT A RAY OF SUNSHINE, THE LIGHT OF HOPE, UNTO THOSE

WAR-SHATTERED

MINDS GROPING IN THE DARKNESS OF MENTAL TORTURE AND PHYSICAL

PAIN

The author gratefully acknowledges the

encouragement and help he

has received from many Digger friends in the writing of this book

and,

in particular, it is his privilege to specially recognize the

services

of Mr A. W. Bazley of the A.I.F. historian's staff, Mr Frank

Dunne

of "Smith's Weekly," Major Ken Prior, managing director,

"Bulletin"

Newspaper Co. Ltd., and Mr T. L. Waugh of the "Northern Daily

Leader."

I could hope that those who have not known war will be privileged to read this really sincere and unvarnished autobiography of a young soldier who, like very many of his boyhood fellows, was cruelly shattered, in war. Something very much more than a plain simple tale this; something more than a wartime autobiography. It breathes a spirit, a faith, and an idealism that used to be—and still is.

A war story, to sadden and to inspire, by one blasted and wrecked in that disaster which was Fromelles in 1916; by one whose optimism has survived uncomprehended tortures since the tide of battle left him stranded, a pathetic fragment of humanity, on the forbidding shores of post-war. A man who is still the light-hearted, fearless boy that used to be, looking back, glad and proud, while not ignoring the tragedy and the futilities, that he was there.

It is a story that, in parts, might perhaps have been written by any one of the 316,000 members of the Australian Imperial Force who felt that their duty called overseas in 1914-18, could their pens trace the inspiration—convert the inner thought. Here is real atmosphere, so elusive always, and difficult to capture and imprison on the printed page—the atmosphere which only the soldier knew and none other can ever create.

The spirit that was of the famous battalions permeates this book and there is stark reality, humour, and incident that take the memory back down the dimming avenue of the past to vivid, wild, joyous, bitter, tragic years, the axis upon which the thoughts and lives of all ex-service men turn.

Here is also an epic of indomitable courage in the after-war, and of a happy spirit, invincible in torture and suffering that cannot even be imagined by those whose bodies have not been torn and hacked in the ghastliness of war and brought again and again to the operating tables, and who have not waged grim war with the leering, luring, drug fiends.

A soldier's soul is here bared.

L. A. Ross.

Sydney,

17 September, 1935.

Greatly I appreciate having been asked to pen this foreword to There And Back, a story which, I am confident, is crowned already with that most difficult distinction, great usefulness. Some outstanding quality must justify any narrative, but, it seems to me, in this one all such qualities are so inextricably mixed that it is impossible to select confidently the impression that stirs one most, for the humorous precocity of the author's initial attempt to enlist is quite overshadowed by an awed comprehension of the lurid dangers into which he was rushing headlong, and the glowing eagerness of his youthful ambition is somehow made pitifully poignant by the cruel price of suffering he was made to pay.

But valour, endurance, and intelligence are the qualities that shine most conspicuously and all unconsciously in these pages, and these things must be an inspiration to every youth who gets this book in his hands. No better trial for manhood could ever be devised than a twelvemonth of service with a wartime battalion of Australian infantry, and the manner in which "Ted" stood this testing, while still only a boy, should strike an inspiring note in the heart of every young man.

Living recklessly, the dangers he faced were tenfold, but the only way a youth can win the admiring confidence of mature men is illuminated here with a clarity unmistakable. The one brief period of strutting and aping at the vices of older men is the clear background against which his sober determination to excel and prosper shows best, and any experienced soldier will instantly descry in him those particular qualities of conduct that were so highly esteemed by Australian fighting troops.

Self-reliance, confidence, and alert service brought him preferment shrewdly bestowed, and ready humour and efficiency retained it.

Any word-monger's easy flowing fancy can capture on dexterous pen the fictitious poses of an ideal hero, but few men can aptly express their own sufferings. The very intensity of this author's agony seeps unknowingly into his words and they sear the heart. Understanding of the awful price in suffering the war made some men pay, should awake anew a watchfulness that the things they held for us are not despised; and a brief comparison of the grim facts in this story with the settled security of our common lives to-day should win an instantaneous sympathy for the author's tale.

While its merits should win a ready praise, it is the humour that flashes in patches of brightness that brings an indescribable stamp of conviction to this narrative, and it builds up a certitude that the writer has told his message in the most fitting way as

The happy warrior...

Whose high endeavours are an inward light

That makes the path before him always bright.

And the characters that live with him also are all striking types recognizable anywhere to-day among returned soldiers, and their story moves with a swinging rhythm, a provocative march-time lilt, that must captivate all veterans of the old A.I.F., as, out from the strange confusion of early camp days, the narrative gathers gradually increasing cohesion and momentum in passing over the seas and crossing Egyptian sands, until, like a curving, rushing wave, it bursts at last with a surging shock on those German breastworks at Fromelles.

Ah, what a tragedy was there, when all Australia felt the crushing weight of war's blundering futility. What a realization it was that war was waged by incompetent men as it always is, for war is a peculiarly incompetent activity. So we must now remember it not as a glory, not as a defeat, but as a cruel punishment for the crime of insufficient understanding of the problem of war. We know now that our strong hand methods have failed, the weapons we used destroyed more than we gained, but this we did, we proved that the problem of war is a moral one, that it is a rotten thing based on rottenness, yet a just scourge from which the world is not yet worthy to be free.

"AN UNKNOWN SOLDIER."

Much water has passed under the bridge since you came on a hurried visit from Tamworth to see me at Randwick Hospital in August, 1932. Though I do not recollect much of what happened, or nearly happened, during the final six weeks of my half-year sojourn there, I do remember your arrival at my bedside as the jolly old Canon concluded his few last words.

Just what he said to help me over the divide I cannot recall, but I am mindful of your suggestion that I should write a book. Maybe you said that in an heroic endeavour to persuade me, during what seemed to you and others to be my last hour, that my life had been worth something to others; or perhaps you thought that, if I did by any chance recover, a little writing to remind myself of the "wickedly" past would keep me quiet for a while.

Well, I tricked the undertaker once again and proceeded to have a fling ere the family returned from Blighty in the ensuing October. After eighteen months of grass-widowership, the process of getting back to domestic paths and taking up the reins to guide the children (still three, in case you are presumptuous) caused me to forget my troubles and recent associations.

My son and heir, aged six, having during his trip abroad witnessed the trooping of the colour, the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, and a military tattoo, informed me, that he, too, was going to be a soldier. Perceiving with mixed feelings of pride and regret that he was made of the same stuff as his father, and being unable to answer his many questions offhand without prejudicing his youthful mind one way or the other, I remembered your suggestion and resolved to put my experiences on paper.

Here's the manuscript. I am afraid it will offend some people with literary and ethical tastes (the war and its aftermath were a bit coarse in parts), and the credibility of others will at times be somewhat taxed. However, it mirrors myself, as I was and felt, and others as I saw them at the time. It is "dinkum;" and that is why in the narrative I have changed my name, and have also referred to others simply by their Christian names or nicknames in case they, like myself, do not like too much of the limelight of truth. There is another good reason why I have used the name "Ted." It is my second Christian name (Edward)—I was called after my father. Then again I gave it to my eldest son, so being well and truly worn, like myself, it is rather appropriate. Furthermore, it gives the Dad a place in the history of his chip—a doubtful compliment to a most tolerant, forbearing, and sporting father—but a tribute nevertheless. To Mother and Father, their fathers and forefathers, I owe everything for the healthy constitution that has pulled me through, and if I, a chip off such a block, am a bit splintered, well it's of my own making.

In writing this story I have lived much of my life over again—the pain, the humility, the bad, all have their place, if only to give one a better appreciation of the pleasure, the pride and the good. In the passing of the kindly mellowing years one remembers less and less the pain, yet how easy it is to recall the pleasures that we had. Some of the old diversions are recalled with feelings of some discontent, Fritz and the surgeons having left me my conscience.

I was not in the battle of the Wazir, or at Anzac, or in the Somme mud, or on leave in Blighty. Mine was a very small part, and it must be multiplied many millions of times before one can form any conception of the four years of war in which I saw but nine days in action. My purpose, however, has been to draw a picture of the war and its aftermath as I saw it, lived it, hated it, and loved it at the time. And, in case another war should ever darken the world's horizon, the following pages may do something to enlighten readers with regard to war.

A. TIVEYCHOC.

1935

A Contemporary review

of the book

01. CHILDHOOD: ABOUT TURN

02. STANDING EASY

03. MARKING TIME

04. THE HEADS AND THE BOYS

05. A SHIP SAILS

06. SYDNEY TO SUEZ

07. TOURING AT SIX BOB A DAY

08. BOYS OF THE SUEZ CANAL

09. TEL-EL-KEBIR

10. GRAINS OF SAND

11. EGYPT TO FRANCE

12. IN BILLETS

13. BOIS-GRENIER-FLEURBAIX

14. FROMELLES

15. BOULOGNE

16. BLIGHTY

17. TOUCH AND GO

18. TROOPS IN TRANSIT

19. COMING HOME

20. HOME AND HOSPITAL

21. WINGIES AND PEGGIES

22. DOPE

23. CARRYING ON

Comes of British stock—Seeks adventure in a sewer—Learns scripture and deportment—Receives a black eye—Plays truant—Wins a prize—Goes to work—Forgets love and tries to join the army.

(June 1899—June 1915)

Edward Rowland, born of Australian parents at Sydney on the 20th of June 1899, was working in his father's factory when war was declared in 1914. His grandfather of the one side and great-grandfather of the other, descended from British seamen (thought to be pirates) and English countryfolk respectively, had been among the first pioneers to settle in Victoria, where they and their descendants engaged in mining, horticultural, and commercial pursuits. It is therefore not surprising that "Ted," coming from such stock, was of sturdy physique, and was endowed with the spirit of adventure and patriotism.

Ted's brief childhood was sufficiently varied to equip him with at least the fundamental requirements of life. Setting out on an adventure at the age of four, he was some hours later discovered in an open sewer, minus his clothes. Later, after running the gauntlet of pneumonia, scarlet fever, and chicken pox, he was placed at a private school where scripture and deportment were the principal subjects on the curriculum. With his natural instincts somewhat subdued by this environment he entered upon a public school education, and within a week was initiated into the art of taking knocks—the first resulting in a black eye.

Following on a lengthy truancy from school during which he built a hut in a mangrove swamp and sailed the shark-infested waters of the Parramatta River in a home-made canvas boat, the boy achieved the not unexpected distinction of coming last in the school examination. A conference of father and schoolmaster thereupon resolved that, as chastisement had proved of no avail, they would try other methods. So Ted received a bicycle from his father and was appointed monitor to his master, and he responded by coming third at the subsequent examination in token of which he received the school's prize for progress—Robinson Crusoe.

Perhaps the adventures of Crusoe or his own satisfaction in considering that he had proved his ability, or perhaps both, gave Ted sufficient excuse for relaxation, but, whatever the cause, the remainder of his school-days were marked by sporting rather than scholastic achievements. He is probably remembered by his school-mates as captain of the footer team and runner-up in the swimming championship, but most of all for his chronic state of black eyes and occasional victories in fistic combat. As a chorister he led the church choir boys in everything but singing, and it must have been a great relief to the verger when Ted's voice broke, and he retired from that confraternity.

Much against his parents' wishes, he left school at the age of fourteen and was put to work in his father's business, where he remained—though, after the novelty had worn off, much against his inclination—for the next two years, up to the time of his enlistment in the Australian Imperial Force.

When the exigencies of compulsory military training allowed, he would tour the country on his bicycle in the holidays, carrying his provisions and sleeping out. On one such trip, which occupied three days, he covered 339 miles in a round trip from Sydney, touching at Burragorang, Wombeyan Caves, Goulburn, Moss Vale, Kangaroo Valley, and Nowra. This was no mean feat for a boy of but fourteen summers, who already had to his credit the saving of two lives from drowning.

If, during June or July of 1914, Ted heard anything of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, it is probable that he promptly forgot it, for at that time his thoughts were mainly centred on a pretty girl who worked in a neighbouring factory. In exchange for penny-dreadfuls and an occasional bunch of violets he was allowed to accompany her as far as, but no farther than, her railway destination, and, as his weekly supply of pocket money was limited, it must be assumed that he booked more than one fare to the then equivalent of "Kitchener."

After the declaration of war his premature springtime fancies turned to thoughts of adventure. Newspapers and military text-books supplanted the penny-dreadfuls, while the scent of violets at least temporarily evaporated. Orators and the sight of so many khaki-clad figures fired his youthful imagination, but his first visit to Victoria Barracks, a suit of overalls covering his short pants, resulted merely in Ted's offer of enlistment being "received" by the sentry at the main gates. It was not until after Christmas of 1914, when he first got into long trousers that he succeeded in even gaining an entry to the Barracks. Taking his place in line with that morning's batch of volunteers he was confronted by a sergeant-major, who did not appear satisfied with the youth's answers concerning his age.

"Know anything about soldiering?" asked the S.M.

"Yes sir," came the ready reply.

"About turn! Quick march! Double!"

Receiving no further command, as he headed for the gate, Ted took the "office."

Though hurt in his pride and feeling wholly dejected, he nevertheless found some consolation in believing that those who predicted the early termination of hostilities might be wrong, and that the war would last more than another six months. So, with the idea of qualifying for the light horse, he saved sufficient money to hire a horse for a week-end, but after the first day's riding found it more comfortable to stand than sit. Next experimenting with a bugle, he had almost perfected the "Cook-house Door" when the patriotic patience of the neighbours petered out, and in silence he sounded "Retreat."

By the time when the news of the landing at Gallipoli arrived, Ted's frequent calls at the Barracks had led to a distant sparring acquaintance between him and the sergeant-major. But, except for his new-found interest in compulsory military training and the recent attainment of the rank of signal-corporal in the Senior Cadets, and three evenings of each week—when he was supposed to be at night school—in the company of a Boer War veteran turned night watchman, the time dragged wearily on to June.

A 16th birthday present—A successful cough—A tail of a shirt—A Liverpool Marmalade—A camp concert and a night without pyjamas.

(June—July 1915)

Sunday, 20 June 1915, was Ted's sixteenth birthday. His parents, fearful lest he should run away from home and join up under an assumed name in another State, compromised by giving their consent to his enlistment conditional upon his entering the signalling corps. It was their fond belief that the training for this unit would take at least twelve months, by which time the war might be over; and it is just possible also that they considered that army discipline might bring the boy's spirit under control.

With the ink hardly dry on this document—his most cherished birthday present—Ted again confronted his friend the sergeant-major.

"What! You bloody well here again?"

"Yes, have a look at this," said Ted, producing his parents' consent.

"What's your age?"

"Eighteen, sir."

"Stand easy."

Which he did with the utmost satisfaction in having, at last, settled his differences with the jolly old sergeant-major.

The rest was easy, being not at all unfamiliar to one who had received "inside" information from many who had been through the preliminaries. Particulars as to full name, date and place of birth, colour of eyes, hair and complexion, weight, and height, were duly recorded, and parental consent noted by a clerk in the recruiting office; and Ted, having expanded his chest, shown feet, said ninety-nine and coughed successfully, was ordered to report at the barracks on Monday, 19 July, ready for camp.

Though elated with this initial success he was conscious of yet a few more difficulties to be overcome. For example, he was a trainee under the compulsory service act, and the issue of a summons as the result of his absence from future parades would of course lead to the discovery of his enlistment in the A.I.F. under the prescribed age. But this was "fixed up" after a friendly talk with his Area Officer, to whom he gave an undertaking to attend as many parades as possible prior to embarking for service overseas.

Then there was the question of his military shirt. Compulsory trainees over eighteen years of age were in the militia and had on their shirts shoulder straps, which were not included on those of the senior cadets. So if Ted's cadet shirt was to be worn to camp it became necessary to make the required addition. A friend apprenticed in tailoring adjusted this matter by making shoulder straps out of material cut from the tail of the garment.

Monday, 19 July 1915, was ushered in with rain. This might have been taken as a bad omen—as events turned out, on the very first anniversary of his signing on for "three years or the duration," Fritz and fate in the Battle of Fromelles extended this period for life. But this was not a day to sit in the shadows of coming events. Rising from his bed after a sleepless night, Ted hurriedly bathed and, dressing in his slightly remodelled cadet uniform, sat down to the family breakfast. What with the incessant questioning of his younger brothers and sisters, the thoughtful silence of Mother and Dad, and his own pent-up feelings, it was with the greatest difficulty that he contrived to be outwardly calm and inwardly fed.

Breakfast over, the youth strapped up his valise and, with a lump—or was it breakfast—in his throat, grinned and said good-bye. Hearing but not remembering the words of parting, seeing without looking back, feeling kiss and handshake still with him, he set forth on the long adventure. On the train he chewed rather than smoked a cigarette, and, after a fit of coughing, received lengthy abuse from an old lady who threatened him with her gamp for being in a non-smoker. Blushing freely he came back to earth, and by the time the train reached Sydney was thinking of the day ahead.

On arrival at Victoria Barracks Ted sought out his old friend the sergeant-major, but if he expected a welcome home he was disappointed, for that gentleman merely ordered him to "wait." Wait! Why, the S.M. knew that Ted had already experienced eleven months of waiting, but perhaps after all, he used the word by way of recognition.

As the recruits arrived they gathered in groups and, the muster being a particularly large one, it seemed that all walks of life were represented. Ted attached himself to the group attired mostly in various cuts of khaki, and was agreeably surprised to find an old school chum, "Dab," some two years his senior. This group listened attentively for a while to the experiences of a New Guinea veteran, and was in the midst of a round of smutty yarns, when without the ceremony of a bugle call the order was given to "Fall in!"

Stepping out and re-forming lines in order of the roll-call effectively split up the groups, and, after numbering, the form-fours shuffle brought Ted in between a seaman and a chap with a bowler hat. As the column marched out of the barracks and Ted passed the sergeant-major, he could not resist a final word.

"So long, Major!"

"So long my boy, good luck!"

The recruits, receiving an occasional cheer as they swung along the road, were conscious of their motley appearance, and it was not until tramping through Surry Hills, when someone produced a mouth-organ, that they found their spirits. Some singing, some laughing, and others cursing the march, they arrived at Central Station and heartily cheered the engine for its whistle of cock-a-doodle-do. Entrained, the starting whistle was the signal for another wild outburst of cheering, which was repeated at each of the first few stations through which the train passed, and then the company settled down. Ted, who had taken a part, though not a leading one, in the cheering, accepted a dainty sandwich from his companion of the bowler hat and, after a gulp from another's bottle of beer, did the honours with cigarettes.

Detraining at Liverpool and crossing the river bridge they entered camp and were greeted by some thousands of their predecessors, who lined the lane-way between the huts and loudly jeered "Marmalades! "—signifying initiation to a camp where marmalade constituted the staple food.

The ceremony of attestation—taking the oath of allegiance, with the Bible grasped in the right hand—reminded Ted of the seriousness of his undertaking, but still uppermost in his mind was the fear of his age being found out. The rest of the afternoon was spent in getting established. Divided into squads they were marched to the quartermaster's store, where each was issued with blankets, dungarees, white hat, boots, socks, flannel shirts, tin plate, knife, fork and spoon. On returning there was a wild scramble for empty palliasses and straw, which had been dumped in the middle of the hut. Though some succeeded in getting palliasses and others had equal success with the straw, Ted, in spite of a good deal of rough handling, was one of the few who got both.

At the final parade of the day, after the orderlies for the morrow had been detailed it was intimated that although no leave would be granted that night, the troops were free to wander within the limits of the camp until 9.30, when they must be in the hut to answer roll call. At 10 o'clock, lights were to be put out. The parade was then dismissed, though not before several unsuccessful attempts had been made to carry out the order.

The evening meal—bread and marmalade, with a pannikin of sweet, black tea—being hurriedly taken, Ted and Dab set out on a tour of inspection. After viewing a cook-house and inspecting the guard, they had a look at the river and discussed it as an avenue for taking French leave, bought some cigarettes and lollies at the canteen and then finished up at the Y.M.C.A. tent where an impromptu concert was in progress. A song about a little grey home in the west was followed by a cornet solo; a humorous recitation was then given a good hearing, but a well-rendered classic on the piano was soon counted out and the concert resolved itself into chorus singing.

Less than the full number put in an appearance at roll-call, but as a reply—in some cases more than one—was received to each name called, it was let go at that. Except for some good-natured chaffing of those who produced pyjamas (Ted left his in his valise), there was comparative quiet for the half-hour preceding "lights out," all being more or less engaged in making preparations for turning in. This, however, was but the lull before the storm.

The scene that followed lights out began with an organized raid, some twenty toughs grabbing the ends of palliasses and pulling them from under their owners, who at first dealt out blows at random and then joined in the raid themselves. It was no time before the whole hut was in a state of turmoil, and more than one suffered as the light-fingered took advantage of the darkness. When a lull occurred in the yelling, shouting, and swearing, the hut sergeant threatened to bring in the guard, but he was promptly told what he could do. He thereupon retired, and the mob sorted itself out and subsided.

Taking stock with the aid of matches, Ted found that, apart from having fallen into the filthy mess of someone's vomit, he had not come out of the raid badly. He had managed to secure a well-filled palliasse in lieu of his own, and had lost only his issue knife, which he determined to replace in the morning.

Indelicate remarks—mostly crude, though occasionally witty—now bandied back and forth, were signals for renewed laughter and rebukes, which, though subdued, were sufficiently effective to keep all hands awake. It was well after one o'clock before peace and quiet, except for a few coughs and snores, reigned in the hut. Reviewing the events of the day, Ted's mind at first dwelt in shame on some of the unpleasant episodes and his minor parts in them, but it was not long ere his thoughts wandered back to the haven of home and in its blessing he found sleep.

Physical jerks and china dogs—A brief command—A returning leave train—Assuming manhood—A sergeant's medicine and duty—Beer and breath lollies—A father's advice—A trip to Melbourne and back to the 30th Battalion.

(July—August 1915)

Awakening with reveille and hurriedly dressing to the skirl of Scotch pipers whose job it was to rouse the camp, Ted was one of the few ready to fall in for physical jerks parade. When at last the late-comers had fallen into line and the sergeant had abused all and sundry, he went into further fits of abuse as he endeavoured to put them through numbering, separating odd from even numbers, and opening ranks. Being sufficiently familiar with the exercises—bending backward, forward and to the sides, bending arms and legs and turning head left and right—Ted had time to concentrate on and marvel at the instructor's versatility. He was picked out and ordered to the front as a good example, but was sent back to the ranks on bursting into laughter when the sergeant suddenly exploded: "Gawd a'Mighty, yer as stiff and slow as a lot of china dogs."

All signs of stiffness however, vanished when the squad was dismissed and the orderlies arrived with breakfast. Had all hands been trained in athletics they could not have been more active in their rush on the dixies.

Ted's khaki shirt, on account of the piece missing from the tail, already had earned him the name of "Freezer;" but it was also apparently responsible for his being detailed to take charge of a squad. And had he adhered to text-book regulations instead of trying to emulate the pomposity of the sergeant who conducted the physical culture parade, he probably would have been made a corporal. At first the members of his squad were bewildered and then indignant at having a kid in charge of them, but resentment turned to amusement and culminated in a wild outburst of laughter, when he stood them at ease and addressed them in the regular sergeant-major style thus:

"Once upon a time when I was a little boy I had a box of wooden soldiers. I loved my wooden soldiers and became more and more attached to them as time went on. Then came a day when we moved away and the wooden soldiers were lost. I cried and cried; and my mother said, 'Never mind, my boy, your soldiers will all come back some day'—and now by cripes they have."

Unknown to Ted, the sergeant was standing behind him as he related this story. After joining in the laughter, the N.C.O. made use of a hefty boot and so it was that Ted, much to his satisfaction yet physical discomfort, was relieved of his short-lived command.

To those with previous experience of military training the elementary stages of drill were most uninteresting, but Ted's sense of humour saved him and he found much amusement in seeing and hearing the awkward recruits being put through their paces.

That night he was given leave. Not waiting for tea he hurried off to the station, his valise containing pyjamas and other articles as did not become a private soldier. Feeling about a foot taller on arrival home, he did justice to his dinner, told Mother and Dad all about the nice chaps he knew in camp, and said that the sergeant was a little bit "rough" but was going to get him into the signallers; and after supper, when he had convinced Mother that it was against orders to wear pyjamas in camp, invited the family to visit him the following Sunday. Then, with a bag of home-made cakes under his arm and head full of advice, he hurried off for the train.

The returning leave train with its mixed freight of humans caused Ted, when trying to sleep that night, to ponder on the strange ways of men. The great majority in that train were of course decent fellows, and they attracted little notice; as usual, it was those in various stages of drunkenness—sleeping, laughing, cursing, crying, vomiting, fighting or arguing—or with immoral women, who gave the superficial observer a disjointed and wrong perspective of life.

Like most others and particularly the younger men, Ted soon acquired the habit of evincing a coarseness of manner, which, though at times causing him to feel inwardly ashamed, served him as a means to outwardly establish and demonstrate his manhood. Adapting himself to all phases of this new life, two weeks' training hardened him to soldiering. He growled with the others about the food, complained with them about the drill, and helped to plan revenge on the sergeant for not allowing regulation rests on the route marches.

Some few miles out on a march one day the sergeant, who for about a mile, had shown signs of discomfort, called a halt. It transpired that someone had put caustic soda in his boots, and so, after placing Ted in charge, he returned to camp. When he disappeared from sight, the troops, without waiting for an order, ambled down to the river with Ted bringing up the rear, and there enjoyed a quiet hour before returning to camp. Whether or not the medical officer diagnosed the sergeant's complaint is not known, but the events of the next day seemed to indicate that he had ordered m. (medicine)—in the shape of a number nine pill—and d. (duty), which, much to the discomfort of the troops, the sergeant carried out with callousness and determination.

After a fortnight's training—during which there flew around many wild rumours known as "latrine wirelesses," and later "furphies," (Furphy being the name of the sanitary contractor at Broadmeadows Camp, Victoria)—the destiny of Ted's "mob" was determined, through its being classified as "C" Company, 30th Battalion. Leaving their palliasses and the much disliked sergeant behind, they now took up residence in a bell-tent encampment farther along the river bank. To be posted to an original unit was the ambition of most recruits; and, although living in tents meant still more congestion and discomfort, it was regarded, at least by Ted, as being more soldier-like. That night he was detailed for the guard, and was looking forward to the experience; but, happening to be the only one to fall-in in a khaki rig-out—the others were still obliged to wear the blue dungarees that had been issued to them at the outset—he was accordingly dismissed from the parade.

A few days later Ted was selected, with others, to attend a signalling school in Melbourne. Much to the envy of those staying behind, they were marched to the Quartermaster's Store and issued with uniforms, numerals, badges and kit-bags. This occurred on a Saturday afternoon, and they were to leave for the south on the following day.

Ted hurried home, dressed in full uniform and carrying his kit-bag. As he walked from his home-station he was very proud of himself and felt that everyone was looking at him, as indeed they were, though probably thinking more of his youthful than his soldierly appearance. Of course he simply had to call and have a pint at the hotel where a week ago he had been refused a drink for being under age. Then, after visiting a few shopkeepers for the sole purpose of answering their anticipated questions as to when he was going away, he bought some breath-lollies and arrived home.

What might possibly have been his last day at home—for the latest "furphy" had it that they would embark from Melbourne—was by no means a happy experience. His brothers and sisters were quiet and Mother and Dad were most serious. Ted had a feeling that they might alter their minds and not allow him to go away. While at odd moments' they did give thought to taking such action, their patriotism and feeling of pride in their son would not allow them to go back on their word.

The silence of father and son sitting side by side looking into the glowing coals of the evening fire was at last broken when the former, overcoming his restraint, warned his son of the many pitfalls of life and particularly those of a sexual nature. When the time came for him to return to camp, Ted assured his family that, although he would be back from Melbourne in a few weeks, he would write to them often; and he made the parting as brief as possible.

That night it was a most thoughtful lad who, after making a hole in the ground for his hip, and placing a waterproof sheet under him, rolled up in his blankets and tried in vain to sleep.

Next day the lad's father visited him in camp and they talked of anything and everything except the subjects of the previous evening, which made Ted feel glad. He introduced Dad to his pals and they all gave good reports. One of the company—the father of an old school chum of Ted, and now affectionately called "Dad" by all the boys—gave an undertaking that he would keep an eye on the lad. This offer was resented by Ted, but much appreciated by his father.

There was a big crowd to see them off from the Central Station at Sydney that night. After the train started, Ted found little chance of thinking or looking back, for a company of Queenslanders, already past the farewell stage, kicked up Hell's own row and caused trouble all the way to Melbourne.

On arrival in Melbourne they marched over Prince's Bridge to the signalling school in the Domain. Obtaining leave, Ted visited his uncle at Moonee Ponds, and returned to camp to find the rain coming through the flyless square tent and his cream blankets covered with mud. That night he wrote home a letter in which he said that he was well and was having a good time; but refrained from mentioning how one of the Queenslanders climbed through a window and scrambled along to another compartment, while the train was going, or of the smashing of windows and window bars on the Victorian train, though he did say something of a fight at Seymour.

It turned out that there had been some mistake in sending them to Melbourne, so, like the Grand Old Duke of York's men who marched up the hill and then marched down again, they arrived back in Sydney after spending only one night in Melbourne. Looking very weary and showing signs of a merry night's journey, they were marched to Victoria Barracks, given lunch at a cheap eating-house in Paddington, and returned to Liverpool, to be posted to headquarters signallers, 30th Battalion.

Once a man always a man—Finding's keepings—A letter home—The battalion moves—Its colonel, his batman and others—A march through Sydney—A fair question—Sundry signallers—A crime and a visit to Hell—Barney and Mrs I-ti—A skating civvie and a bandy batman.

(August—November 1915)

Ted soon found his cadet-gained knowledge of signalling to be very elementary, yet his experience in Morse and semaphore "flag-wagging" was a good foundation for the more advanced training.

He liked the sham stunts in which three signallers would be sent out to man each visual signalling station. Sent out one day with Jim J. in charge, and another signaller who, like Jim, was ever ready to make way for youth when there was work to be done, Ted had had about two hours' continuous flag-wagging when he received the welcome message "emma-emma-esses" (M.M.S.)—meaning, "men may smoke." Ted was about to light up when Jim said, "Did that message say anything about boys may smoke."

"No—why?"

"Well, put your fag out."

Jim was promptly told to go to hell, but, being a good fellow and always too tired to exert himself, just rolled over and went to sleep.

An expert telegraphist, Jim considered that his effort towards winning the war would be confined to his skilled calling, so, except for taking part in route marches and in the general routine, he was never known to work. He would come back merry from leave and call out, "I've had two flounders, four bob each, and now I am going to assert my prerogative. If there's a man amongst you let him announce himself." One night someone did, but Jim only put out his hand and said, "Well I'm (hic) glad to meet you; once a man (hic) always a man (hic)—'ave a drink."

It was about this time that Alan L. ("Rubberneck") joined up with the signallers. Detailed to Ted's tent, he could not understand why all but one, Vic C., slept on one side of the tent. "This'll do me," he said as he dumped his gear down alongside Vic, but, having been kept awake all night with Vic's snoring, he woke up to the idea. Vic was the grand champion of snorers, and even a half-open box of matches lighted on his nose failed to cure him.

Tom H., the corporal signaller, was also an occupant of this tent. He took great pride in his hair and was most careful of his personal appearance and effects. One Sunday, after leaving camp with a lady friend whom he was taking to Sydney, he returned hurriedly from Liverpool station looking the picture of misery. During his absence Ted had found a pound note in the lines and, saying "finding's keepings," had promptly visited the canteen and also paid a deposit on his photograph. He was enjoying a good feed when he was surprised to see Tom come back.

"What's up, Tom, had a row?"

"No, I've lost a quid."

"Struth! Tom, that's bad luck. Have a piece of cake?"

Bronchitis and meningitis were very prevalent at the camp at this time, and Ted contracted the former complaint. The sergeant, going on week-end leave, allowed Ted to sleep on his stretcher in the store tent, and it was from there that Ted wrote home the following letter:

DEAR MOTHER AND DAD,

I am unable to come home this week-end as I have a bit of a cold.

It is nothing much, so don't worry. I am sleeping in the sergeant's

real bed in the store tent and will be well enough to go on parade

to-morrow.

My bed faces the tent opening and I can see all the funerals that

go along the road from the hospital. The band plays the "Dead

March" with the drums muffled in black and the soldiers march with

reversed arms. They go by very slowly and the music makes me feel

as though I am in the funeral—I don't mean in the box. I

suppose in time we will get used to such sights.

Toc R., the O.C.'s batman, went on leave to the country, and I am

supposed to take his place. I don't like the idea of being a

servant and cleaning boots, but suppose I'll have to do as I am

told. You should have seen Toc going on leave. He had infantry

breeches, light horse leggings and spurs he called 'ooks, a

coloured artillery sig.'s badge and two stripes on his arm, signal

corps badges on his shoulders, crossed flags in front of his cap, a

white naval lanyard sticking out of his pocket and rolled overcoat

across his chest, carrying a basket hold-all, signalling flags,

riding' whip and umbrella, and leading Tiny, our dog mascot, on a

piece of rope that kept getting tangled around his bandy legs. Toc

has flat feet, and Jack F. says he is built for trench warfare.

I have had my photo taken and will send you one with this letter. I

will try and get leave on Thursday night and will come home to

dinner, and I would like you to make some sausage-rolls for me to

bring back to camp.

It is feared that Ted took good care to be a failure as a batman. The light duties of this office, cleaning boots, polishing leather and metal, making the bed, bringing shaving water, cleaning up and folding up were more or less welcomed as a period of convalescence, but both he and the O.C. rejoiced when Toc came back to camp complete but for his umbrella.

During the month of September the battalion was transferred from Liverpool to the Royal Agricultural Showground in Sydney. The change was greatly appreciated by all ranks, for it brought the city within easy distance of the camp. The made roads and grassy training areas of the adjacent Moore Park were a decided change after the sticky, oozing mud or thickly flying dust of Liverpool. By this time, as a result of the training, and the issue of uniforms and equipment, and of horses for the senior officers, the mob had been converted into something approaching the appearance and standard of an infantry battalion.

The 30th had for its colonel a tall and, but for a moustache, most unwarlike-looking man with a highly pitched voice, who sported a shrill pea-whistle. He lived with his bulldog in the show-ground glass-house, and had for a batman an Englishman named Silvertail. This man's name, when called by the colonel, was music in itself. It was "Silvertail, Silvertail, how many more times am I to tell you not to wrap my pyjamas in a wet towel?" Also "Silvertail, I like my toast done a nice golden brown;" and, later, in France, "Silvertail, there's a beastie on my singlet, take it away from me, Silvertail, take it away!" But for all that, as the real test of soldiering later proved, the colonel was a great soldier; and it is doubtful if there was ever a more efficient batman than his Silvertail.

Next in command was Major H., a thick-set, dinkum-looking major with a florid complexion and suitable deep voice for giving military commands, as well as expressive colour to his Aussie vocabulary. He differed from the C.O. in every audible and apparent respect, even to the shade of his khaki and the leather polish he used. Later he was given command of another battalion.

With the leaders' contrasting qualities of ruggedness and blandness more or less serving to compensate each other, the H.Q. of the battalion also had an adjutant, one Captain S. A regular soldier, senior in age and military experience, he gave balance to the command and sympathetic understanding to those commanded. Affectionately known as "Tod," his pecuniary lavishness recouped more than one digger's loss at two-up, and at other times provided the wherewithal for sight-seeing and various kinds of recreation in Cairo and other pleasure resorts.

The battalion was divided into four companies, which in turn were divided into four platoons each of four sections. Each company and platoon had its O.C., and each O.C. had his peculiarities and eccentricities. For instance, there was Major B. of A Company, a crack rifle-shot, and known as "Cock Robin" for the one and only song he gave at each battalion concert. Though at one time he had a company of Queenslanders who proved as impossible for him to manage as did their two mascot monkeys, his command now for the most part comprised Victorian naval men from Williamstown. This change of personnel he welcomed, but he found some difficulty in converting them from naval to military practice. On one occasion Sergeant Tosch reported as to so many being "aboard sir," the number "ashore sir," and the names of those "adrift sir"—which, interpreted with the retention of but one "sir," turned out to be a report on the number in camp, on leave, and absent without leave (A.W.L.).

In accordance with "establishments," the battalion absorbed transport, machine-gun, and signalling sections, as well as a band which, under the leadership of Sergeant Les W., had by this time gained the reputation of being the best of its kind in Australia. The 30th was thus as complete and evenly balanced as its brief history and available equipment would permit.

The battalion's 1st Reinforcements joined the unit at the showground. "Come on, brighten up and sing a song," said their O.C. (Lieutenant Mac) when they were straggling along on a march. The boys accordingly struck up "We'll Hang Old Macfarlane on the Sour Apple Tree"—and that was the last time he called on them to sing.

To celebrate and demonstrate its advent, the battalion, wearing the latest type of equipment, made of green leather, and with its accoutrements highly polished, marched through the streets of Sydney. With the signal section leading, we fall into step with Ted and share with him the countless thrills that travel up and down his straight and youthful spine to the accompaniment of inspiring martial music from the band.

By the time the marching column reached King Street Ted felt as though he were walking on air. As it wheeled into George Street, the sight of a girl falling from one of the top windows of a store through the awning to the pavement below momentarily prompted him to break from the ranks and run to her assistance. But though he felt that as a participant in the march he was in some way responsible for the accident, he carried on, and was brought back to his bearings when an acquaintance on the sidewalk in Martin Place advised him that he was the only one in step.

Stanley E., the youthful lieutenant in charge of the signallers, was pinched in countenance and full of military theory; but, despite his swanky little ways and schoolmaster attitude, was a likeable chap. Instead of calling the members of his section boys and treating them as men, he addressed them as men and tried to manage them as school children. Military training and school teaching were to him synonymous terms, and Sam C., a Cambridge University graduate, took much delight in subjecting his newly found tutor to humiliating ridicule.

Stanley took great pains to instil into his men that they were the eyes and ears of the battalion, and, impressing upon them the necessity of being observant in all things, he invited questions on their observations. At one such question time Sam sought some information.

"Sir," he said, "for some time I have been giving my utmost concentration to a question not only of wide interest, but, might I say, of vital importance to the battalion in regard to the holding together of its command. With all the intelligence and power of observation that I, like my fellow signallers, have acquired from your teachings, sir, I regret to say that my research in the subject has, owing to my humble status as a private, been restricted, and I am unable to proceed to a definite determination of the final phase. And now, sir, I respectfully seek your aid and enlightenment, since you, as a commissioned officer of His Majesty the King, and commanding officer of this intelligence wing of our unit, are more favourably privileged to observe the finer points of the subject, which to my mind is the mainstay of the battalion command. Could you tell me, sir, if it is B.D. or D.V. corsets the Colonel wears?"

When the laughter subsided Sam came in for severe reprimand and, when the class was dismissed, he was given twenty alphabets to send by Morse flag. Ted received similar punishment for being the most outstanding with his laughter.

Sam, who liked to demonstrate his superior learning, wore underneath the collar of his tunic a stiff white collar, the feeling of which probably served to keep him from sinking into the uncouth habits of a soldier. But at times he would get a little bit rough and argumentative under the influence of higher class drinks, which he was careful to talk of for fear one might presume he had been partaking of common beer.

The signal section—excluding its sergeant and Toc R., the O.C.'s batman—comprised twenty-three men. With three signallers of the 1st Reinforcements, they were billeted in what had been a furniture showroom, which was like a home away from home, though without palliasses the floor was something of a disadvantage. The front opened on to a veranda where a trestle table served for taking meals, as well as for buzzer practice and card games. It was not until the night before leaving these premises that the erstwhile tenants discovered that gas was still connected to a meter in the room, and, when the main pipe was lit, the resultant five-foot flame served as a farewell beacon.

B., otherwise "Perlmutter," whose Yiddish cobber, Albert G., was called "Potash," slept on a locker in one corner of the bare room. One night, after they had returned from leave partly under the influence and given an acrobatic display in the nude among the rafters, Perlmutter sat fair in a bucket of water which had been purposely placed on his locker.

Rex, Reg, and Peter were the reinforcement signallers, and, as such, were looked upon by the originals as being below their standard. This view had no real foundation, for the length of service of these three was equal to that of the others, except Jack F. and Tom H., who had seen "active" service in New Guinea. (Those two, by the way, were wont to tell of the special service medal that was going to be struck for that campaign.) It is doubtful, however, if the reinforcement signallers ever felt any inferiority in their position. They were morally, socially, and generally in accord with each other, and, being so admirably suited, had no occasion to consider this other "secondary" status. The foundation of their friendship was, despite some difference in religious creeds, based on their code of moral ethics. That they did not adopt an attitude of aloofness, but joined in the collective amusements of the section was an influence for their good as well as for that of the others. It tended to broaden their outlook while at the same time rounding off the rough corners of others, for, if army life taught anything, it taught tolerance of the ways of men.

Other signaller friendships were for the most part based on some mutual characteristic or interest, yet the friendship of Eric W. and Bill M. was at first hard to understand. The former was a parson's son whose main interests lay in the direction of eating, sketching and photography, while of Bill it was said that he was writing a correspondence language course for bullock drivers; but each soon became an apt pupil of the other and they were almost inseparable.

Jim J. and Eric S., apart from being telegraphists by profession, were also united in their ideas of recreation, and in the art of elbow-bending they were about equal. Vic W. and Vic C., with names if nothing else in common, were also members of the "bar," as were Potash and Perlmutter and, later, Eric W. and Bill M. Alan L. (of furphy fame) was intelligence officer of the froth-blowers' circle, while Barney K., an ex-lightweight champion of the navy, was chief chucker-out and music maker.

Intellectual superiority and its finer tastes for both humour and edibles brought Sam C. and Dud C. to a state of perfect friendship, towards which Tom H. was ambitiously attracted and admitted on account of his somewhat polished mode of speech. On their returning to camp one evening Ted invited them to join him in his supper of fish and chips and beer, and was severely crushed by Sam's reply—"Fish and chips! Why we have just dined at Paris House!"

C.C. being the code letters for the word "cipher" in the signalling service, it was but natural that C.C.S. would be nicknamed accordingly. Cipher was of an inventive turn of mind, and at the time of his enlistment was in the midst of inventing some patent kind of headlight that would automatically project round corners. Jack G., an "umteenth" marine engineer, whose neat appearance was his outstanding social qualification, proved a suitable mate for Cipher. There was in the section another Jack G. who, having been a senior clerk to Stan (the O.C.) in a shipping office, apparently felt he had to keep up the dignity of his late position by playing a lone hand.

Other members of the section included Ron C., a close friend of the reinforcement signallers, yet even more adaptable than they were to the social requirements of soldiering. He shared with Ted the distinction of having a tunic embellished with officers' embossed oxidized metal buttons, and was the owner of a safety razor which Ted, receiving it as a parting gift, had exchanged with him for ready cash. Then there was Reg H., whose twin brother was on Gallipoli. Reg was another of the signallers' saints, and, when provoked in excited argument, as was frequently the case, because he was a good "bite," the only wickedness he was ever known to utter was "Ah, me tit!" Bob T., according to the nautical experiences he was ever ready to relate, was evidently born at sea, where he must have lived for about eighty years to have travelled so far and wide. Jim S. found pleasure in everything but shaving, though he had a kit of six or more razors with which to attack his wire-like growth; he was, without exception, the most obliging and unselfish one of the crowd. Wal C. was unequalled for his dryness of humour and his running capabilities, a most happy combination which was to serve him well in France. What Mac M., a ginger-headed Scotchman, lacked in humour he made up for in honesty; some ten years after the war, he went to no end of trouble to locate one of his Digger creditors with whom he insisted on settling a ten-bob debt. In 1915, however, Ted was in Mac's black books for having helped himself to the latter's gold-tipped cigarettes.

Ted had so far made no particular friend in the section, being evidently satisfied to be one of the company and on good terms with them all. His youth no doubt excluded his being welcomed into the froth-blowing circle of the hard heads; and, as the company of the wise heads would have cramped his style and made his youth more apparent to himself, if not others, he—well, just carried on.

One morning Ted was carrying on at the top of his voice, abusing all and sundry, when Major H. came in hearing, and promptly crimed him for using bad language. Ted was sorely tried all that day, and, though he came in for a good deal of chaffing from his cobbers, refrained from repeating anything of his morning address. Some told him that he would be given No. 1 field punishment and lose at least twenty-one days' pay, others that he would be "shot at dawn." He found that night to be a very long one. The hard boards on which he continually turned in trying to get to sleep were harder than ever before, and when at last he did go off, it was only to dream of even worse punishment than had been predicted by his mates. After he had faced the firing squad and received its issue of lead, his subconscious mind—taking a different course from that of most dreams—went travelling on through hell, where the devil took the form of the major who was gladly assisted in his tortures by all the signallers, and to make matters worse, he had been struck dumb. After ages and ages of continuous torture and just when he felt that he was about to die again, he heard the sound of Gabriel's trumpet, and awakening in a cold sweat, he found voice to curse the long drawn out blast of Lofty B.'s trombone in the adjoining shed.

Before the time arrived for orderly room parade, Ted paid an unofficial call on the major, who was then dressing and had evidently enjoyed a better night's rest than the lad, for, after receiving an apology and advising him to refrain from using such terms of "endearment," he withdrew the crime sheet. Ted, feeling that officers were not such inhuman creatures as he had previously imagined them to be, thereupon enjoyed a good breakfast and took added interest in the work of the day.

That night he and other signallers went to the Union Jack Club at Petersham. The club was run by a number of patriotic young girls, whose sole object was to entertain anything filling a khaki or naval uniform, and to send white feathers to those males who preferred civilian dress. They gave freely of lemonade, cakes, sweets, and kisses, and otherwise entertained with music, dancing, and games. In return, they were entertained by the troops, of whom Barney K. was their favourite with his sailor ditties, particularly the one that went "I-tiddle-i-ti, one for Mrs I-ti, slap her in the other eye," and so on. Barney, sitting on the floor among a bevy of pretty girls joining him in song, laughed and joked and sang with the same assurance that he had employed all the way out in the tram when not otherwise engaged in argument with the conductor over the troops' refusal to pay fares. "Book it up to Kitchener," he would say, and would then go on with "Farmer Brown, 'e 'ad a little farm, down on the E.I.O."

The roller skating rink at the Showground, opening as it did on to the street and into the ground, provided a good avenue for those taking and returning from French leave. It also afforded plenty of opportunity to those who liked this form of thrilling recreation, and furnished a handy, though in some cases last, meeting-place with members of the opposite sex. A flash civilian, expert in the art of skating, took much delight in upsetting the equilibrium of the troops not so skilled as himself. Ted suffered several falls in this fashion, and waited three successive nights before squaring the account, almost breaking the civvie's neck. Barney's challenge to a duel with or without skates was not accepted by the civvie, nor was the floor of the rink afterwards graced by his presence.

At this time the daily routine of the signallers commenced with physical training, a break for toilet, breakfast, and dressing for parade. Afterwards they would assemble with the rest of the battalion on the ground at the rear of the skating rink, where Major H.'s deep bass would bring the parade to order and he would hand it over to the colonel, who with the aid of his pea-whistle made himself promptly understood, despite his highly pitched voice which gave much amusement to the troops. The battalion would then get under way in its daily march to the foot of Mount Rennie, led by the band playing its regimental march.

At Mount Rennie the battalion split up for either company or platoon drill, while the band returned to camp to practise and the signallers got on with their visual training, which sometimes took the form of all-day stunts and resulted in their being spread out over the landscape as far as the sand-hills of Botany. They also had Morse buzzer practice and theory training, as well as instruction in infantry manoeuvres and rifle drill.

One day when both the O.C. and the sergeant were away, Toc R. led the signallers at the head of the battalion, as he was the proud possessor of two stripes to which, by the way, he was not entitled. Toc the batman had not previously been on a parade with the 30th, and, had not the colonel been immediately behind the signallers when Toc performed a fancy evolution with his signalling flag as he wheeled into the street, the boys would have all burst into laughter. Toc's left wheel resembled a tramwayman on point duty eurhythmically posing as Mercury in search of somewhere to go, and no doubt he was glad when his bandy legs and flat feet eventually got him there.

When the battalion made arrangements to stage a military tattoo, the signallers, because they were supposed to know something about telephone wires, were given the job of erecting electric-light poles in the show-ring, and for some years after the war these stood as the only visible monument to their existence as a unit.

Final leave—A village party—The last night—Embarkation—Cheers, shrieks and streamers—The Governor-General's furphy—The Heads and a first cigar.

(November 1915)

So congenial was the Showground camp, the spring weather, and conditions of training interspersed with liberal leave, that the two months preceding embarkation passed quickly, and during the last few weeks of that period the troops went on final leave in relays.

Ted, now a sun-tanned youth of five-feet-six and weighing ten stone two, was in perfect condition, and in his khaki uniform looked ready for the feast of Mars. His final leave was spent at home, visiting and being visited by friends and relations the majority of whom bored him stiff with their patronage and well-meant words of advice. They all said how brave he was and how well he looked; some asked him to kill a Turk for them, but most wanted the life of some sausage-eating, barbarous German. All said much the same things concerning his welfare welfare and safe return to Australia, and asked him to write often and tell them about the war. Then a final "Good luck," "God speed," or "Goodbye," along with a shake of the hand or a pat on the back or a kiss.

Ted and his old school pal, Dab, were given a send-off by some of the village boys and girls. Apart from the red, white, and blue decorations, a bunch of Allies' flags with the Union Jack placed upside down, and the uniform of the guests of honour—who remained seated to their toast while the company sang "Australia Will be There"—it was the usual merry party of youth as in peace-time. Of course Ted and Dab received much attention from the girls, who were ever ready to kiss and be kissed; but, as this happened to be Ted's debut, he was rather shy. and did not warm up to the idea until it was time to go.

He walked home with a buxom bunch of sweetness who, in that hour of her hero worship, wanted more than the one kiss he gave her over the garden gate, but Ted, like Ginger Mick—or was it the Sentimental Bloke?—knew not what the 'ell to do with his two hands. Yes, he agreed they should write to each other, and he promised to keep her miniature photograph, which, by the way, was resting in a silver match-box that kept company throughout the war with the identification disk hanging against his chest from a piece of string tied around his neck. On the way to his own home under the stars of a cloudless sky, Ted meditated on the beauty of her countenance and the warmth and brightness of her being, and, imagining the sweetness of her presence still with him, decided he was in love.

Mother and Dad, waiting up for his return, may have guessed something of his feelings from the flush that penetrated his tan, but any serious thoughts they may have entertained were quickly relieved by the hearty manner in which he disposed of the dainty supper Mother had prepared. He told them about the party, and was saying something of the girl he had taken home, when Dad came to his rescue and saved further explanation with the reminder that it was long past time for bed.

His almost worn-out bicycle he handed over to the elder of his two young brothers, but he put away other souvenirs of his youth, such as his first suit of long-'uns, and his one and only school prize (the inscription on the fly-leaf of which he glanced at with a grin). The family having promised to visit him in camp on the evening before embarkation, this made his leaving home more easy, but more than once he looked back and wondered if he would ever see the place again.

On the Sunday preceding departure Ted attended the battalion church parade at St Andrew's Cathedral. Next day the unit was paraded to hear the C.O.'s address to his officers and men, but beyond the words "King and Country," "traditions," "duty," and "victory," Ted heard little of that stirring speech, for he could see his people on the "outer" waiting to say good-bye.

Mere words cannot adequately portray the emotional and touching scenes of that evening, when over a thousand of Australia's manhood parted, many for ever, from those they loved. Some walked With the maidens they adored, no doubt whispering sweet vows of eternal love. Some parted from mothers who held and pressed them to their hearts again and again, and said nothing. Others parted from wives sobbing in awful fear, some of them accompanied by children yet too young to understand the tears. That rough old diamond Barney butted in everywhere with his cheery laughter and happy songs, and, as Ted and his mother broke their long embrace, Barney called, "Good-bye, keep smiling, Mum!"

Ted's father was waiting at the gate of the camp when, at 4.45 a.m. on Tuesday, the 9th of November 1915, the battalion swung out on what for many was to be their last march on Aussie soil. Many members of the tramway volunteers, between whom and the 30th there had been some unfriendly feeling, also gathered at the gate in various stages of undress, many of them in bare feet, and they cheered the departing troops in unison. One chap with a voice reminiscent of a barracker's voice on the hill of the Sydney Cricket Ground, was heard to ask that they leave him a few Turkish tarts in the harem, and someone else advised suitable though unmentionable treatment for the Kaiser.

When the battalion was marching at ease, Ted's dad, with one of Ted's kit-bags under his arm, took the opportunity of having a few last words with some of the signallers, and Ted would have been greatly agitated had he known that Dad had confided his son's age and a few other things to the O.C. As the column neared No. I wharf at Woolloomooloo Bay, Dad again took his place alongside Ted, and, as he hurriedly handed over the kit-bag, the youth saw, through his own dim eyes, a tear on the strong yet smiling face of Dad, and received, without any self-conscious feeling, the emotional kiss of parting before he passed through those now historic gates to the troopship.

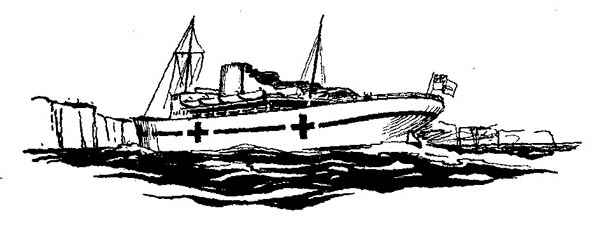

After officials had checked up the embarkation roll and found all present and correct, they ordered the disappointed section of reserve men to return to camp, as there were no deserters' places for them to fill. Then the troops filed up the gangway and boarded the troopship A. 72. Breakfast of porridge and sausages was waiting on the mess-tables as the signallers took up quarters underneath the for'ard well-deck.

They were in the midst of doing justice to the meal when Lieutenant Mac (O.C., 1st Reinforcements) discovered they had taken the position allotted his men. As he stood there frowning like fury, and with arms folded, Sam loudly asked Tom if he had ever seen the famous picture of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, and as Tom turned round to view the picture, Lieutenant Mac, red with indignation, said to Sam: "Are you trying to be funny at my expense?"

"Oh no, sir, I was merely referring to something of an historic character," replied Sam.

"Because, if you are," continued Mac, "you'll find that I can be much funnier at your expense." And, to the titter of subdued laughter, he took himself off.

With breakfast disposed of, the signallers moved across to what was the corresponding position on the right, or as Barney called it, starboard side of the ship, and after being issued with hammocks and rough, cream-coloured blankets, which they stowed in bins, they were allowed to go on deck.

When at 8.30 the public, after two hours' enforced waiting, surged on to the wharf, a great cheer went up from two thousand khaki-clad figures who, swarming from mast-heads, rigging, and railings, almost blotted out from sight the superstructure of the ship. For the whole fifteen minutes preceding departure it was just one long cheer, above which could be occasionally heard loud and piercing shrieks of women, until finally the blast of the siren announced that the ship was getting under way and the fussy little tugs took charge of her. There was now a break in the cheering as the band played "Auld Lang Syne." Thousands of multi-coloured streamers, at first brightly waving, then slightly tugging, grew taut and finally snapped to hang forlornly in the hands of those who, now speechless, would for ever remember that day.

When the vessel pulled into mid-stream, the ferries greeted it with shrill whistles of cock-adoodle-do. After the Governor-General had given an inspiring address to the "gentlemen of the light horse and men of the infantry," in which he dramatically mentioned they were going on special service to a new front, Alan Rubberneck got busy with his furphy wireless and gave it out that the Dardanelles had been forced and they were bound to back up the Russian "steam roller" via the Black Sea. A rumour from the aft latrine then had it that Mesopotamia was to be their destination; and at dinner-time there was much argument, which was only rivalled in importance by a discussion on the merits of the menu.

Having waved to the fleet of launches grown dim in the distance, and finally cheered the last cock-adoodle-do of a Manly ferry, the ship passed through the Heads at three in the afternoon. At last the long drawn out farewell had come to an end, and Ted, with sickly grin and believing no one to be looking, dropped his first but only half-smoked cigar over the side.

First thoughts—From hammock to officers' mess—Housie, banker and crown and anchor—A church parade—A dark horse and a fair cow—A concert and crossing the line—Maggots and weevils—Suez.

(9 November—11 December 1915)

Most Diggers sailed with a diary, few wrote them up. Ted's is reproduced here.

H.M.A.T. "Beltana" (A.72). At Sea, Nov. 9th 1915.—It has just gone 5 p.m., and according to the joker in the crow's nest, gazing out to sea and not taking the least notice of the chaps feeding the fishes—all's well. What with the excitement of the day, that damned cigar I'd saved for the occasion, and the sight of pickles on the mess-table for tea, it is little wonder I'm not feeling too good myself. Anyhow, I'm not the only one, and for that matter I guess the folk at home are feeling a bit off their tucker too. My thoughts up to now are mostly about what others are thinking, and I am worried about the sadness of Mother and Dad at home. I feel sorry that I have caused them so much trouble, but I am relieved to be at last on the way, for I know now that they will not call me back. Barney has just informed me he and I are mess orderlies for to-morrow, and, as the thought of it makes me feel like showing visible signs of seasickness, I'm going up on deck.

Thursday, Nov. 11th.—It is 8 p.m. and here we are again. Some of the boys are playing banker at one end of the mess-table, and a game of housie-housie is in progress on the hatch. As mess orderly yesterday, I managed to dish up the boys' tucker and keep mine down. It is rougher now, but I'm feeling better, so don't suppose I'll be seasick after all. The daily routine, according to orders, is to be: Reveille 6 a.m., physical jerks, 6.45 to 7.30, breakfast 7.45, parade 9.30 to 11.45 (with half an hour smoko), dinner at noon, parade again 2 to 4 (with a quarter of an hour smoko), tea at 4.30, and lights out at 9.15; no afternoon duties on Saturday, and only physical drill and church parade on Sunday. Counting church parade, because it is compulsory or optional to peeling spuds, the actual working hours on this voyage will total twenty per week with pay at the rate of two shillings per hour; and as food, if you can eat it, is chucked in, a soldier's life at sea in terms of ?.s.d. is not too bad. Of course between parades there's always some fatigue duty to be done.

The hammocks, much more comfortable than bare boards, are strung up over the mess-tables in formation, so that you have the heads of two and feet of two other of your neighbours meeting on either side about your middle. The lights go out, the latecomers scramble in and are cursed for their bumps, someone sings a song and is told to shut his bloody mouth, a smutty yarn brings wild laughter while the wowsers go crook, and then, gently swaying to the motion of the ship, we fall asleep. As the troops are packed like sardines above the line of port-holes, the air becomes thick with the smell of smoke and bodies; awakening with reveille, we hurry to the deck and wait in long lines taking deep breaths of the fresh salt air, as we push those in front and curse the slowness of the early birds, who seem to have taken up permanent residence in the improvised and much too small wash-houses and latrines.

After stowing hammocks and blankets, we eat some canteen biscuits, and then a bout of boxing gives interest to the physical jerks parade. Sitting on forms at the bare board mess-tables, we await the orderlies, who come very carefully down the steep companion-way, carrying porridge, stew or sausages, and dippers of vile-tasting tea. We laugh as one of the orderlies, holding a dish of stew with both hands, falls ace over head from half-way down the steps, and we add insults to his injuries. Had it contained sausages we could have picked them up, but Tiny, our mongrel mascot, is already licking up the mess, and for us it only means waiting a little longer, for, as lots are suffering from seasickness, the galley has a surplus supply of food. Some; more finnicky than others, just pick here and there at the food, while a few, loudly complaining of the tucker, scoff it down their uncouth necks at a rate that is only checked by their belching after long gulps of the stinking tea.

The morning parade of the signallers if one is not detailed for duty on the bridge, is taken on the boat-deck. The usual flag-wagging and buzzer practice with the same old lectures will, no doubt, be dished up to us time and time again. We have to speed up the sending and reading of Morse to about thirty words per minute on the buzzer, and as Jim and Joe can do about forty they are marking time. Sometimes they talk to each other in Morse, and, judging by their amusement and the few words I pick up, "indulge in personalities," as Sam would say.

Each of the three courses of the midday meal tastes about the same, but perhaps that is because the soup spoons and the fork of the second course have to be used for the sweet. To-day's sweet consisted of plum duff, which was promptly labelled "guttapercha-pud," and, as (according to my dictionary) gutta-percha is a reddish-brown horn-like substance of inspissated juice of a certain tree, I reckon it's a good name. If the ship gets torpedoed when the men are carrying a belly full of this tack, they'll sink like stones.

This afternoon we had some instruction about the mercantile international code. In between parades most of the boys play card games and housie-housie, the latter being the only money game allowed. The most enjoyable part of the day, however, if you don't think of the good things they are eating, is the evening officers' mess when the band plays selections. I have just returned from the boat-deck, where, being alone, I feasted on the music, and, in the fading light of the setting sun, let my mind wander back to the old folk at home. Somehow I like the lonely feeling that comes over me at sunset, but I must not mention this in my letters or they'll think I'm homesick, which at this time of day, I truly am.