Amazon - Website

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

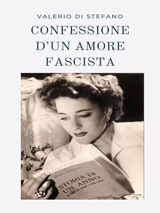

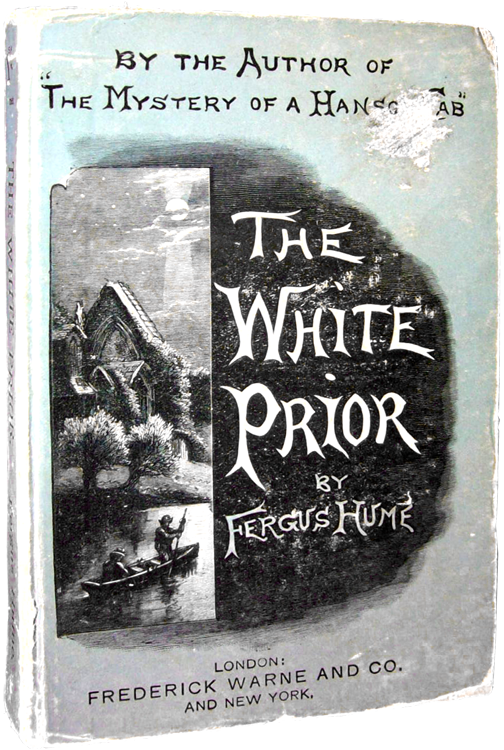

Title: The White Prior Author: Fergus Hume * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1800501h.html Language: English Date first posted: June 2018 Most recent update: June 2018 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Chapter 1. - The Tutor

Chapter 2. - First Impressions

Chapter 3. - Tresham’s Diary—Suspicion

Chapter 4. - The Pupils

Chapter 5. - Monkish Tales

Chapter 6. - Tresham’s Diary—A Midnight Episode

Chapter 7. - An Interesting Conversation

Chapter 8. - A Round of Pleasure

Chapter 9. - Exit Mr. Harley

Chapter 10. - Tresham’s Diary—The White Prior

Chapter 11. - A Terrible Discovery

Chapter 12. - Fate

Chapter 13. - Gilbert is Dismissed

Chapter 14. - Amateur Detectives

Chapter 15. - The Revelations of Miss Carr

Chapter 16. - Tresham’s Diary—The Lovers

Chapter 17. - Strange News

Chapter 18. - In the Crypt

Chapter 19. - The Truth

Chapter 20. - Tresham’s Diary—Wedding Bells

With the impatient egotism of six-and-twenty, Gilbert Tresham assumed that he was hardly treated in being relegated to a country life, shelved as it were, at the fighting age of intellectuality; and, but for the small matter of poverty, he would have remained by preference in London. A novel, a play, a volume of poems, a book of essays, on these rested his hopes of fortune and fame; but as all had been rejected by the publishers, his prudence, inherited from a Scotch mother, inclined him to fall back on his teaching capabilities. He lacked money, friends, and influence; so cautiously resolved to wait, until he had one of the three, at least, to aid his ambition. With characteristic promptitude, he acted on this resolution, and hence found himself in a second-class smoking carriage on his way to a tutorial appointment at Marlow. Foolhardiness is not valour, and Gilbert, who was difficult to please in the matter of literary form and style, acted wisely in declining Grub Street and its pot-boiling work.

This he knew, and was content to abide by his decision; yet, so hard was the battle of inclination against common-sense, that he could not suppress a sigh, as the train slid out of the bustling station; and later emerged from the canopy of smoke which overhangs London’s lights, into the fertile country.

To create characters for stage and novel was more tempting to one of his imaginative temperament than to instruct the intellect of a dull lad; and without looking forward with absolute repugnance to his task, Gilbert had but little relish for the employment to which he was condemned for want of money. The most masterful spirit cannot always control the rebellious flesh, and the young man had considerable difficulty in forcing himself to take a calm view of his situation.

He had opportunity to indulge his disgust without restraint, as the compartment was tenanted solely by himself; but in place of wasting time and strength in futile rage, be threw himself on the cushions and, lighting his pipe, abandoned himself to philosophical reflections. With the lucidity of a trained thinker, he reviewed his life so far, from what he remembered of his childish years, to his present position in the twenties. Between that and this had occurred the many events which made him the man he was.

Hitherto, to use a hackneyed image, his life had resembled a placidly flowing river pursuing its course over a smooth bed, through peaceful plains. If he had not known wealth, he had not felt the sting of poverty and from nursery to school, from school to college, from college to London, he had had a singularly uneventful career. To recur to the above-mentioned image, no shoals had impeded his course, no rocks had fretted the even flow of his waters, but on and on his days, like the stream, had glided unchecked, unvaried, undisturbed. But now the river of years was rounding a curve, and it was impossible to prognosticate in what tortuous windings it might flow.

Left an orphan at an early age, Tresham had been consigned to the care of a bookish uncle who was the rector of a Devonshire parish. His father, a captain in the army, had perished in one of the frontier wars of the Empire, and had shortly been followed to the other world by his attached wife. Kind friends dispatched the orphan of three years to the care of the Rev. Simon Tresham, his paternal uncle; and henceforth, to the age of seventeen, Gilbert had dwelt on the verge of Exmoor. His relative, a kindly old creature, albeit rather given to dry-as-dust pursuits, had taught the lad excellently well; and when he was entered at Exeter College there were few undergraduates possessed of sounder learning, or a wider range of subjects.

The sombre existence in that quiet rectory had somewhat shadowed the spirit of the lad, and he was grave beyond his years. Though no mean athlete, as was testified by his well-knit frame, he affected the library and class-room rather than the river and cricketfield; being resolved, as he early stated, to devote himself to literature. To this end he studied hard, and left Oxford with a brilliant record and an M.A. degree. Thence, with the approbation of his uncle, he repaired to London, and in a shabby Bloomsbury lodging sought to amplify his scholastic lore by a knowledge of city life.

Gifted with talent, and scholarship, and indomitable perseverance, he would doubtless have achieved those first difficult steps of Fame’s ladder; but that Fortune, as though regretting her former liberality, placed a hindrance in his path. Hardly had he been settled a year in London when his uncle died, and Gilbert hurried down to the Exmoor rectory to find himself a friendless pauper. What small income the Rev. Simon Tresham possessed died with him, and, with the exception of two hundred pounds, the young aspirant to letters was without funds. Nevertheless, such an amount seemed riches to one of his habits, and he re-entered the turmoil of London with every hope that he would be enabled to gain bread by his pen, before his capital vanished.

But as time was the most necessary of all things to complete the magic draught of Mephistopheles, so is time requisite to gain a name and fortune. The first unsteady steps in the literary profession are very slow, and require to be well planted in order to avoid a retrograde movement. A man may have the genius of Shakespere, the perseverance of a factory-begotten millionaire, and yet remain years in London without being able to thrust his head and shoulders above the thronging millions of the city. No doubt to such a one the chance comes, but Gilbert could not afford to wait for the propitious moment. With the strictest economy he was unable to make his money last for more than eighteen months, and with the utmost perseverance he failed to get a book published, or a play read. Many men would have fought their way onward with the strength of despair, but Tresham was sufficiently wise to see that such penury and hasty work would strangle his small measure of genius. He was not a great man, and at the best possessed only a bright and lively fancy which, polished by culture, might enable him to arrest the ear of the public. To speak honestly, he lacked power, and his literary ramblings were rather produced by artificial incubation than by material inspiration. His small creative germ was amplified and polished and tended until it grew into a bright flowering shrub, pretty enough to look at, but without the enduring qualities or grandeur of the oak. He worked slowly, and polished incessantly, so above all things required time to produce his works in a sufficiently dainty guise to attract attention. Hitherto, despite all efforts, his delicate wares had met with no appreciation, and when his money dwindled down to a score of pounds he found himself compelled either to renounce his ambition of moderate fame, or—sad alternative—to resign himself to the heart-breaking profession of a literary hack.

Then his maternal inheritance of prudence came to his aid, and he resolved to make use of his teaching capacities to gain bread. In the retirement of such a situation, he thought, he would be able to produce and send forth his fragile literary children, and at the same time be enabled to live comfortably and take time over his work. To this end he inserted an advertisement in several newspapers announcing his qualifications as a tutor, and after many disappointments was engaged by Mr. Vincent Harley of the Priory, Berkshire, to instruct his son and heir in the rudiments of the classics. The wage offered was small but certain, so Gilbert, not without regret, turned his back on literary London and took a second-class ticket for Marlow. From this brief review it will easily be seen that the comparison of his life to a river, smooth flowing and tranquil, is not lacking in point.

Having endowed a hero with but mediocre talents, eked out by indefatigable industry, and a vein of prudence, justice demands that his physical attributes should make amends for his mental deficiencies. But alas! Tresham was no Greek god of supernal beauty, and would be scorned by the frantic lady novelist, who draws her hero with the brain of Plato and the looks of Alcibiades. Again must Tresham sink to the level of the mediocrities, for he was simply a long-limbed, well-looking youth, with a kind face and an attractive manner. There are as many as good as he in England, for, despite the wailings of pessimists, our country produces as fine a crop of honourable stalwart lads as ever it did; and our little wars in savage lands show that English pluck and honour are as noticeable characteristics of our men of to-day as they ever were in the golden times of Elizabeth, and no higher character than this is necessary to any Englishman, much less to modest Gilbert Tresham. Once and for all in Amyas Leigh did Kingsley set forth the noble qualities of our islanders, and it were folly to add to or to take away aught from that grand type of our race.

It being thus stated that Tresham was a well-educated, athletic, and honourable English lad, there is nothing more to be said in his favour or against him. He lay on his back watching the yellow gaslight looming through clouds of smoke; and having grumbled a while, as is the fashion and privilege of our insular youth, shook himself free of regrets, and addressed himself to take an intelligent interest in his journey through the fertile lands of Berkshire.

It was a wet night, and the driving rain blurred the window-panes so that he could see nothing. Sometimes the lights of a village twinkled through the gloom as the train rattled past, but for the most part there was nothing but fields and hedgerows looming indistinctly on either side. Tresham found no interest in such monotony, and so betook himself to the re-reading of a letter from his friend Barstone, who had been mainly instrumental, along with the advertisement, in procuring him the appointment. The letter, among other things, hinted at the quality of the inmates he might expect to find in the Priory.

“Harley is a quiet old man,” said the letter, “rather whimsical and bookish. For weeks he will shut himself up in his library and see no one; then throw open his house, and invite the country-side. He is attended by an old valet called Jasper, with whom you should make friends, as he is all-powerful in the house—a dumb creature he is, savage and morose; and, evidently fearful of losing his influence over Harley, watches him as a cat does a mouse. He resembles a Turkish mute, misanthropic, silent, and evil. The housekeeper is a lady-like personage, whom I have only seen once, but is very melancholy, and looks like a mediaeval abbess of some especially strict convent. And talking about convents, Harley’s house, as you can guess by its name ‘The Priory,’ formerly had something to do with Catholicism. It is said to be haunted by the ghost of a guilty monk—though in what his guilt consists I don’t know. At all events, my dear Tresham, he strolls about the grounds at night, and if you are afraid of ghosts don’t go near the west wing. Your pupil is a pale-faced, delicate lad, who seems to me to have water on the brain; but you will no doubt find him easy enough to deal with. His sister Fay is—an angel.”

From this point the letter resolved itself into a series of ecstatic paragraphs about the said young lady, and Tresham had no difficulty in seeing that his friend Barstone was in love with her. The college career of that young man had been chequered by numerous episodes of a like nature. “And no doubt he will marry the girl,” thought he, returning the letter to his pocket. “It will be an excellent match, as Barstone’s acres lie contiguous to those of Harley’s. I wonder he doesn’t warn me against falling in love with Miss Harley. But there’s no fear of that, and even if there were, I should curb my passion, as she certainly would not look twice at a poor tutor.”

By this time the train had reached Bourne End, and Gilbert transferred himself and his baggage to the Marlow train. The progress of this latter was sufficiently slow, but he amused himself in speculating on the characters of the four people with whom he was to spend the next few years. The idea that the Priory was haunted appealed to the superstitious side of his nature, and he was quite determined on exploring the west wing. “Don’t nail his ear to the pump,” cried the old woman of the culprit, and it was immediately done. “Don’t go near the west wing,” wrote Barstone, and Gilbert forthwith determined to pay an early visit to the same.

At Marlow station he found a carriage awaiting him, and he was soon rolling over the bridge towards the Priory. On either side rose houses and hedgerows—these gave place to an avenue of trees—then between massive stone pillars the carriage passed into the grounds of his new home. As it stopped at the porch the door opened and a flood of yellow light poured forth; “a good omen,” quoth Gilbert, the superstitious “light in darkness.”

After his dreary journey Tresham was by no means sorry to find himself seated before a well-spread table in a comfortable room, and did full justice to the excellent meal provided by the hospitality of Mr. Harley. Owing to the lateness of the hour he hardly expected to see his employer that evening, and had already turned his thoughts towards the final pipe and subsequent retirement, when an elderly man abruptly entered the room. The new-comer, whom Tresham rightly guessed to be Jasper, was a lean, cadaverous creature, neatly arrayed in black broadcloth. His clean-shaven face was as impassive as that of the Sphinx, and his grey hair was plastered smoothly on his egg-shaped skull. Deferential as he was in manner, Tresham took an unreasoning dislike to his stealthy movements and sinuous obsequiousness; nor was this feeling of repulsion lessened when he remembered that the man was dumb.

Of this latter failing he had immediate proof, for Jasper held in his hands a packet of small cards. Selecting two of these he placed them before Tresham, who read on the first, “Mr. Harley,” and on the second, “The library.” Rightly interpreting this as a request that he should so seek his host in that room he was about to reply, but reflecting that Jasper was probably deaf as well as dumb, he took out his pencil to communicate by writing. To his surprise Jasper picked up the cards and touched his ears with a nod to intimate that he could hear.

“You are not deaf then?” asked Tresham, in some astonishment.

Jasper shook his head, and hastily produced another card on which was printed “An accident.”

“Poor fellow,” said Tresham involuntarily; but instead of being pleased by this mark of sympathy, Jasper looked angered, and again thrust before the tutor the card inscribed with his master’s name.

“Very well,” said the young man, smiling at the odd creature, “I will follow you at once.”

Jasper gave a nod of satisfaction and led the way down-stairs. These were of mahogany, dark and dreary in appearance, and but dimly lighted, so that following in the wake of his dumb guide, Tresham became aware of a sudden depression of spirits, as though something evil were in the air. Impulsively he touched Jasper’s arm, as they paused at the door of the library.

“Is this place haunted?” he asked anxiously.

The idea had only entered his head at that moment, and was but an idle caprice of the imagination which he hardly expected to be taken seriously.

Jasper stamped furiously, and his face assumed a sinister expression as he showed a card on which was written “Lies! Lies!! Lies!!!” Then producing another inscribed “Silence,” he ushered Tresham into the library before he had time to recover from the oddity of this behaviour. The chance remark had so raised the ire of this man that Tresham fancied he must have unconsciously hit the mark.

If the stairs were dimly illuminated amends was made in the library, which was one blaze of light. It seemed to Tresham’s bewildered eyes as though a thousand tapers flamed on all sides; but he soon saw that the actual number of these was trebled and quadrupled by skilfully-placed mirrors, which intervened between the well-filled book-shelves. Surrounded by vast sheets of looking-glass on all sides, the room seemed to extend indefinitely, and Tresham felt himself seized with vertigo when a glance upward revealed a ceiling wholly of mirrors. In the blaze of light, in the multiplicity of reflections, there was something monstrous and fantastical. Duplicated in every direction, he felt as though he were in a world of ghosts.

“Welcome to the Priory, Mr. Tresham,” said a voice behind him; “I trust you had a pleasant journey.”

“Thank you, yes; very pleasant,” stammered Gilbert, turning towards the speaker. “You must excuse me, Mr. Harley, but I feel somewhat dazed. These mirrors!”

“Yes, they are confusing to one not accustomed to them,” replied Harley smoothly. “Sit down here, Mr. Tresham, and let us talk. Later on I will introduce your pupil to you.”

The owner of the Priory was a slender, refined-looking man, attired in evening dress, with a precision which argued a scrupulous regard for appearance. A little below the middle height, he seemed but a frail creature, bloodless and weak. His narrow feet and delicate hands were almost feminine in size, and the latter especially, with long fingers and carefully-trimmed nails, struck Gilbert as unpleasantly like the claws of a bird. A perfectly white complexion, fair hair, and pale blue eyes completed his etiolated appearance; and the man looked like the last offshoot of an exhausted race, effete and worn out. A languor pervaded looks and movements which assimilated him to some pale flower secluded from the vivifying influence of sun and wind. In him his race had reached its end, for it seemed impossible that so sapless a twig of the family tree could put forth another shoot. Yet he had a son and a daughter; and Gilbert shuddered to think what weakness weakness had produced.

“Will you have a glass of wine, Mr. Tresham?” said Harley, pushing forward a decanter of port. “I don’t like drinking by myself, yet am obliged to do so owing to the absence of company and to my constitutional weakness; I am not strong, and wine makes blood.”

Gilbert silently acquiesced in this remark as he accepted the invitation, and looked curiously at the frail being, lying weak and exhausted in the depths of the arm-chair. A breath would have blown him away, yet despite his physical weakness he was sufficiently spirited, and talked brightly to his visitor.

“I hope you will like the Priory,” said he, languidly sipping his wine; “we are a quiet folk here, and I do not think you will have much trouble with Felix.”

“Is he backward, Mr. Harley?”

“Not in some things, but in others very much so. The fact is, the lad is stuffed with fiction and poetry—both bad for a delicate boy. I wish you to induct him into a course of profitable reading. Keep him at Latin and Greek, Mr. Tresham, for he is very backward in the classics. However, I give you full permission to act as you think best,” added Harley, with a faint smile, “for Sir Percy Barstone has given me a most brilliant report of your teaching capabilities.”

“Sir Percy is most kind, sir. It is true that I helped him to pass his examination, but beyond that I have no experience in teaching.”

“Nor has Felix of learning,” replied Harley amiably, “so you are both novices. Do you like this room, Mr. Tresham?”

“Honestly speaking, I can’t say that I do. The multiplicity of mirrors, and especially those on the roof, give me a sensation of vertigo.”

“Ah, you are not used to them,” replied Harley complacently. “I like those innumerable reflections because they make me feel as though many people were present. I hate solitude, and I cannot go into society on account of my wretched health, so I hit on this plan to provide myself with silent company. Sitting here with my wine before me I feel as though I were in a cafe on the Boulevards.”

“An odd idea, Mr. Harley.”

“Very odd,” assented Harley, with a sidelong glance at once inquisitive and defiant; “but there are many odd things about this house. Felix, for instance. Here he is! the ghost of what a boy should be! I wish he were stronger,” finished the father, with a sigh.

Towards Gilbert came a duplicate of his host, as bloodless, as white, as frail. The lad was arrayed in a black velvet suit with a lace collar, and looked not more than ten years of age. In his pinched features, Tresham could descry a likeness to the father, and the wan smile with which he greeted his new tutor was reflected at the moment in the pale lips of Mr. Harley. Tresham never beheld a more pitiful sight than these exhausted creatures, who were suffering for the sins of their race.

“This is Mr. Tresham, my boy,” said Harley, drawing his son towards him. “Shake hands with your tutor, Felix.”

The lad put out a thin hand and weakly pressed that extended to him by Gilbert. He was by no means shy, nor was he on the other hand forward: his listless nature seemed incapable of asserting itself either way. He simply greeted his tutor with languid indifference, and afterwards returned to the end of the library, where he buried himself in a big book. There was something painful in the lifelessness of so young a child.

“You must change all that,” said Harley, indicating his son’s occupation; “the lad is killing himself through his brains.”

“With your permission I shall not keep him too close to his books,” observed Gilbert, who had been reflecting on his mode of procedure. “The boy must stay in the open air. Can he swim, Mr. Harley—or row, or ride?”

“He can do none of these things,” replied Harley, with a mortified look. “I am sorry to say it, Mr. Tresham, but the lad is a coward.”

“I think that is a rather unfair judgment, Mr. Harley,” said Gilbert, after a pause; “the face is not that of a coward—it expresses indifference only. Let me guide him as I think fit, sir, and I promise you he will soon wipe away that reproach. He needs exercise and open air; so I will first harden the body and then improve the brain. Unless the first is healthy, it is useless to attempt anything with the lad.”

“Do what you think best, Mr. Tresham,” said Harley graciously, “and I have no doubt that you will be aided well in your endeavours by my daughter. She is the exact opposite of Felix, and is never indoors. I believe she is outside now, notwithstanding the rain.”

Further remark on the part of Mr. Harley was rendered impossible by the unexpected entry of the young lady in question. While Tresham and Harley had been talking she had rapped at one of the French windows at the further end of the library, and had been admitted by Felix. Now she bounded into the room, clad in a mackintosh shining with rain-drops, her face glowing with health, and her dark hair glittering with wet. As Tresham rose to his feet, he was positively startled by the contrast between this brilliant vitalized woman and the anaemic manhood of her father and brother.

“Don’t be so noisy, Fay,” said Harley, with a shudder, as though her sudden entry jarred on his nerves. “This is Mr. Tresham, the tutor of Felix. My daughter, Mr. Tresham.”

“How do you do, Mr. Tresham?” said Fay, in a gay and hearty voice. “I hope you are not shocked by my entering by the window. But I went down to the boat-shed to see about my dingy, and came in yonder as the nearest way.”

“It saves time, Miss Harley,” replied Gilbert, smiling, “and time is precious in this century.”

“Not with us,” retorted she promptly; “we are the idlest people in the Thames valley. You will find it difficult to make us work, Mr. Tresham.”

“Am I then to have you for a pupil?” said Tresham, seeing that Harley had retired to speak to Felix, and in nowise adverse to a merry word or so.

“If you care to. I have been to school, but I am terribly backward yet. Not much better than Felix, poor child. Come here, Felix,” she said, swooping down on her brother and catching him in her arms. “This is the gentleman who will make you a great man.”

“Don’t, Fay,” retorted the boy peevishly, “you wet my clothes. I don’t want to be a great man, but a poet.”

“Oh!” interposed Harley satirically, “then a poet, according to that definition, is not a great man.”

“I would rather be a general than a poet,” declared Fay, who was rolling up her loose hair in front of a mirror. “I wish I had been born a man.”

Privately, Gilbert thought she had more of the masculine element in her than had her father or brother; but of course he did not venture to express so bold an opinion. He was greatly attracted by the exuberant vitality of this girl, and wondered how the exhausted tree of the Harleys had borne so lusty a blossom. Her presence in the room was like a breath of salt sea air penetrating the sickly atmosphere of a hot-house; and her bright manner and merry voice quite dispelled the gloom which he had experienced since entering the library.

But he had little time for these reflections, for Fay, declaring that she had to be up early for a row on the river, bade them good-night, and swept out of the room like a whirlwind. With her departed all the feeling of reality, and Gilbert once more became conscious that the library was ghost-like and uncanny. Like the prince in Tennyson’s poem he felt as though he moved amid a world of ghosts.

“My daughter’s manner is rather trying to one’s nerves,” said Harley, in an apologetic tone, “but I wish Felix was more like her.”

“Oh, Felix will soon be as fond of the river as Miss Harley appears to be,” said Gilbert, taking the boy’s hand. “We are going to be excellent friends, are we not, Felix?”

“Oh yes,” replied the lad passively, and slipped away to his reading, whither he was followed by his tutor.

“Come, Felix,” said he laughingly, closing the book, “you are under my charge now, and as a first exercise of my authority I must ask you to go to bed at once. It is not good for little boys to stay up so late.”

“Very well, sir; good-night,” replied Felix, with the same indifference, and left the room in a weary manner, as though he were worn out.

“What do you think of him, Mr. Tresham?” asked Harley anxiously; “will you be able to make anything of him?”

“It is rather hard to say at present,” replied Gilbert dubiously. “I’ll try, and if I can make him like his sister I shall be more than satisfied. And now, Mr. Harley,” he added, holding out his hand, “if you will permit me I shall say good-night also, as I am weary with my journey.”

“Good-night, Mr. Tresham,” said Harley, with a languid shake. “I like you, and think we shall get on very well together.” After which intimation of good-will, Gilbert retired to think over his first experience in the Priory. It was an odd one, but subsequent events at the Priory proved of so strange a nature, that he no longer wondered at his curious reception by the curious inhabitants of this ghostly mansion.

June 1st.—I have now been over a fortnight here, and I am more perplexed than ever at the singularity of this household. The air is charged with mystery, which affects the mansion and its inmates; but what such mystery may be I have not the slightest chance of discovering. The domestic arrangements are well ordered and admirably carried out, the servants are attentive and deferential, and there is no lack of money to render life easy. Yet withal I do not like the idea of continuing under this roof, as the influence of the place is anything but healthy. I seem to be waiting for the happening of some event—what I know not—and the suspense is at once trying and tantalizing.

It is a beautiful old place: on three sides the grey walls of the house; on the fourth, the broad-breasted Thames; and within this quadrangle green lawns, ancient trees in the full glory of their summer foliage, and flower-beds brilliant with colour. My rooms are in the east wing, which stretches riverwards, and I look out of my windows at the west wing, which directly faces them. This latter is shut up, as the house is too large for its company; and with its curtainless windows and closed doors it presents a somewhat desolate air. Here local opinion holds that a ghost resides—the spectre of a mediaeval monk who makes things unpleasant by revisiting the scenes of his earthly life. Curious in such mystical matters, I have frequently watched the west wing at midnight; but I have been punished for such folly by seeing no sign of the phantom, and by catching a bad cold. Since my experience in that way I have left the haunted house severely alone. The White Prior—as the ghost is called—affects the disused chapel at the end of the west wing, verging on the river.

Admission is gained to the quadrangle through a covered archway slanting diagonally through the house on the west side. This leads to the park, and a winding drive down to the gates, which are usually kept closed, as though Mr. Harley expected a siege. In front of the west wing a fine line of oaks stretches to the river, and as they are now in full leaf, they mask, to some extent, the dreary desolation of the house behind. From the lawn steps lead down to the river; and across the stream stretch fertile fields, and still further rise wooded heights which close the view very pleasantly. On the left of the quadrangle there is a boat-house where the madcap, Miss Fay, keeps her dingy, and in this she is constantly on the river. A terrace runs along the main building facing the river, and is diversified with marble statues copied from Greek masterpieces. On the whole this country-house fulfils Tennyson’s words, as a house of ancient peace, for at all times, and under all lights, dawn and morn and twilight, it is one of the most beautiful places I have seen. A man could do worse than dream away his life in so tranquil a nook, but here the tranquillity is pictorial, for the restless feeling which pervades the whole house is inimical to poetic dreams and lazy days.

After which sufficiently vague picture of my surroundings, I must break off for the present, and retire to rest, for it is long past midnight. I have just looked out at the west wing, but see no sign of its saintly spectre....

June 12th.—Five people here puzzle me greatly, and as I wish to note them closely, it may be as well to set down their particular characteristics in detail.

Mr. Harley: He is a strange creature, as changeable as a weathercock, as whimsical as a woman. For days he will sit in that horrible room of the mirrors, and look at his thin figure indefinitely repeated on all sides; then changing from taciturnity to loquacity, he will emerge from his retirement to make himself agreeable. He is a well-read and largely-travelled man; so to an inexperienced youth like myself his company is decidedly pleasant. When in his good-humoured fits he invites me to join him at the dinner-table, and pours forth a mind stored with memories of foreign climes, of foreign courts, and numerous famous people. He has been everywhere, as appears from his intimate knowledge with the four quarters of the world; he has seen everything and every one: so he can amuse for hours without tiring his listener. Why so brilliant a man should shut himself up in seclusion puzzles me: he is fitted to shine in society, yet prefers the fantasy of his library, untenanted save by himself and his reflection in the mirrors. During his silent fits—as I call them—he is only attended by Jasper, though how he can endure the company of that sinister mute is more than I can understand.

Jasper is not a human being, but a creation of fiction who has in some unexplained way escaped from a novel into real life. He appears to have taken a dislike to me, and when I venture within the precincts of the library, he invariably produces a card inscribed “Go away”; as it would be folly to quarrel with the poor creature, I laugh and obey. His mode of making himself understood by means of the cards is decidedly original. Written by himself in a neat round-hand, every emergency is provided against by the remarks thereon. Sometimes he combines two or three cards, so as to form a sentence, but for the most part one suffices to explain his purpose. When Mr. Harley wants me at the table Jasper’s card of invitation is worded “Dinner,” whereat I nod, and he disappears. The other day he showed me a card on which was written, “Don’t watch the west wing,” from which I guessed that he knew of my midnight vigils. In answer to this I made some remark about the ghost; and was confronted with the word “Fool.” Since then he has left me alone, and I have no doubt that my superstition has lowered me in his good opinion. Felix: A more difficult task I never undertook than to instruct this lad. He is by no means dull, and on his favourite subject of poetry can talk volubly enough; but for the most part he is taciturn, and listless, and indifferent. The poor child is so anaemic that he appears to have no spirit, and I might as well try to vivify a lump of dough, as to induce him to take an interest in the doings suitable to his age. In pursuance of my idea regarding his health I take him out daily on the river and teach him rowing; also I instruct him to swim, and I have already asked Mr. Harley to get him a pony, so that he may become a good horseman. But the result is dispiriting, for he is indifferent to all things. He rows when I place the oars in his hands, he swims when I plunge him into the water, yet he does both with a pensive weariness which makes my heart ache. He is so thin, so bloodless, so weak that I cannot believe he will live long; but with this régime of open air and exercise I hope to rouse him to take a moderate pleasure in existence.

With his studies he gets on better, and is particularly fond of Greek. Arithmetic he abhors, but takes great pleasure in composition, and also in reading poetry. By means of his love for these things I hope to gradually win him over to the drier studies, but owing to his passive resistance, I fear that the attempt will take a long time. It is difficult to do anything with so flabby a creature.

Mrs. Archer: This is the housekeeper, who well bears out Barstone’s description. She is stern and pale, stately and reticent, the very type of a mediaeval abbess. We have exchanged a few words, but she usually goes about her duties in silence, and rarely comes near the room wherein I study with Felix. Twice or thrice I have noticed her looking at me in a curious manner, but when conscious of my notice she has always glided away. She does not like Mr. Harley, for when he was one day giving her directions in his usual finical style, her face assumed an expression of absolute repugnance, and she made her exit from the room as speedily as possible. Jasper does not like her, and greatly resents her approaching the library. Indeed, this strange mute seems to hate all save his master, for whom he manifests a dog-like devotion, which is complacently accepted by the egotistic being on whom he attends.

Fay: I have left this young lady to the last, because I wish to dwell long on her personality. Barstone is right; she is an angel, and merits all the eulogies with which he so plentifully besprinkled his letter. How she came to be the daughter of Harley I do not know, as neither in looks nor temperament does she resemble him in the least. He is a bookish, peevish invalid, who is afraid to let the breath of heaven blow on his frail body; while she is a lusty, buxom girl, who is stifled within doors, and escapes on all occasions into the open air. Just past the age of eighteen, she is singularly free from artificiality, and behaves towards me more like a comrade than anything else. We are excellent friends, and I am more attracted by her personality than I dare acknowledge even to myself. With no position, or money, or friends, how can I hope that she will look favourably at me? Yet her unworldliness inspires me with hope that she will choose as her heart dictates. But, alas! her heart is quite untouched, and she is as frank and friendly to me as though I were her brother. As for myself, even in the few weeks I have known her, I feel drawn to love her—pshaw, what folly! I should not set it down even here. The prize is not for me, but for Barstone, who, judging from his enthusiastic letter, is fathoms deep in love with this Diana of the Thames.

These five people are my constant associates, and one and all they keep me at arm’s length. With Fay I get on admirably, as she is the most human of the five. But the elfish Felix is as reserved as his father; and the dumb Jasper, the stern Mrs. Archer, view me with suspicion. What they think about me I do not know, but so anxious have I become, I am determined to find out. What they are to one another I wish to learn. Why does Harley shut himself up in his library? Why does Jasper watch him so incessantly? and why does Mrs. Archer hate her master? Only time can answer these three questions....

June 24th.—I have seen, if not the ghost, at least the light which is said to be carried by the spectre. Looking out on the moonlight sward at four o’clock in the morning, for Mr. Harley had kept me till late talking, I saw a light flitting from window to window of the dark range opposite. As the door of admission to that portion of the house is always locked, I knew it could not be the servants, and for the moment I actually believed that the radiance was supernatural. Suddenly it disappeared, and though I watched for some time, it did not appear again. I note this in my diary, and to-morrow I intend to make inquiries as to who was in the west wing so late.

By these extracts from Gilbert’s diary it can be easily seen how he was affected by his environment. There was no possibility of ennui while he remained at the Priory. His existence there, simple even to dullness, seemed to him to be but the prelude to some tragedy. The apparent placidity of successive days concealed a constant unrest, an indescribable menace; there was an uneasy feeling in the air, a sense of mystery, of danger, which strung up his nerves, and rendered him expectant of a bolt from the blue. In such wise does Fate prepare the stage for the enacting of her tragedies.

Yet despite this unhealthy frame of mind, which was alien to his temperament, he by no means neglected his duties. Indeed he found himself less averse to teaching than he expected, but this was due to the nature of his pupils. He had two, for Fay, notwithstanding some faint objections on the part of her father, insisted upon studying with Gilbert, on learning the lessons of her brother, and leading him to a comprehension thereof. Tresham was rather glad than otherwise, as Felix was a difficult child to manage, and only Fay, to whom he was deeply attached, could guide him in the right way. The lad inclined to poetry and day-dreams; so it needed all Gilbert’s tact to induce an abandonment of such unhealthy leanings. Had it not been for the sister’s aid he would have failed with the brother.

As it was, he gradually weaned the child from poems, and pictures, and abstract musings; he gave him easy tasks which, being rapidly mastered, stirred him to an ambition to conquer more difficult lessons. While teaching him Latin, Gilbert fired the boy’s imagination with the stirring tales of the Roman sway, and so led him on to study, in the hope that he might read these stories for himself. For mathematics Felix evinced a strong distaste, but when Fay gallantly took up the study of Euclid, and pored over algebra, Felix, dominated by so excellent an example, followed in her wake. His weaker mind was subjugated by the stronger will of his sister, and while it was Gilbert who placed Felix on the path of learning, it was Fay who induced him to progress thereon. Often and often did Tresham confess to himself that without this girl he would be able to do nothing with the boy.

One hopeful sign was the pleasure Felix now took in out-door sports. Tresham taught him to swim, and many a good plunge had they in the river while yet the dawn reddened the sky. Swimming led to rowing, and every afternoon Felix of his own free will would ask his tutor to take him out in Fay’s dingy. Sometimes Tresham would go out with her alone, and talk of many subjects as she laid her strong young arms to the oars. In lawn-tennis Miss Harley was an expert, and between her and Gilbert the little lad began to take pleasure in the game. This constant indulgence in out-door life led to the result anticipated by Tresham, for Felix, his body strengthened by exercise, no longer cared to creep in-doors to read a book, but much preferred being with his sister and tutor in the open air. So far had Gilbert succeeded with his unpromising subject.

Fay was greatly pleased with the tutor, and showed her liking by a constant wish to be in his society. In many ways she was very childlike, and talked so freely to the young tutor, that even had he had the will, he would not have dared to open his heart to her; she was in a state of primeval innocence, and he was unwilling to be the serpent to induce her to eat of the tree of knowledge. That he loved her was patent to himself; but she was quite unaware of his passion, and indeed, in her present state of mind, she would not have understood even had he told her of his feelings.

That two young people should be so constantly together without rousing the passion of love in the heart of one or the other was not to be expected. Fay was too unsophisticated to understand the danger, and indeed entirely escaped it, for she treated Gilbert with a frank friendship which at once pleased and annoyed the young man. He had fallen deeply in love with her, but he saw plainly enough that she had no understanding of the situation. To her he was but a pleasant companion; to him, she was the one woman in the world. Yet he was afraid to tell her the truth lest it should put an end to their companionship; but he made an effort to see if her heart was capable of understanding his passion, by introducing the subject of Barstone.

On the morning that he did so, Fay had finished a set of tennis with him, and they were now seated together under the shade of the oaks fronting the west wing. Felix was knocking the balls about in the hot sunshine, and seemed so alert and bright that his sister could not forbear commenting on his changed disposition.

“I am sure father ought to be greatly obliged to you, Mr. Tresham,” said she, fanning herself with her straw hat. “Felix is another being since you took him in hand.”

“I think he is,” replied Gilbert; “but I should have done little with him had you not assisted me.”

“I could do nothing before, at all events. It needed some one like you to wake him up; in fact, to wake us all up,” continued Fay, with a burst of confidence. “Oh, you can have no idea how dull life is here.”

“I don’t think it is, Miss Harley.”

“Oh, I don’t mean now; it is very jolly at present. But before you came I thought I should go melancholy mad. I was at school near London you know, and there I had plenty of companions, but when I was finished and came home a year ago I found things awfully slow: my father always shut up in the library, Felix buried in his poetry books, and that horrid old Jasper prowling about like a ghost.”

“But your neighbours?”

“Oh, they only call when my father comes out of his shell. Once in a while he behaves like a Christian and gives parties.”

“Is that what you call behaving like a Christian?” asked Gilbert, unable to suppress a smile.

Fay burst out laughing.

“I call it behaving like a sensible man,” she replied briskly. “Why should he live like a hermit? If he doesn’t care for society himself, he should at least remember that he has a daughter to marry.”

Gilbert looked down at the turf and abstractedly plucked a few blades of grass, as he answered in a low tone. Her careless remark troubled him more nearly than he cared to admit.

“Are you then anxious to be married, Miss Harley?”

“Oh, I suppose so,” was the careless answer. “All women should marry, shouldn’t they? I don’t want to stay here all my life.”

“You might find a worse place: this is very peaceful.”

“And very dull. I don’t like the Priory! Father is so gloomy, and infects everybody else with his misery. You are the first human being I have had to speak to since leaving school.”

Here was Gilbert’s opportunity, which he seized at once.

“Nonsense; you know my friend Barstone,” said he significantly.

“Oh, Percy Barstone? Yes, he lives yonder,” replied the girl, pointing across the river. “Sometimes he pays us a visit and talks rubbish.”

“What kind of rubbish?”

“Oh, about poetry and love, and the union of hearts. I believe he wants to marry me.”

“Well, you said it was women’s mission to marry,” muttered Gilbert ironically.

“Only to marry the man she loves,” retorted Miss Harley, with great dignity, “and I don’t love Mr. Barstone. If he wants to take a wife there’s Jemima Carr?”

“Who is Jemima Carr?”

“Oh, she’s a neighbour of ours. Manages her own farms, you know. Not pretty, and over thirty years of age. A clever ugly old maid she is, and I love her very—very much.”

“Ah! but you see, Mr. Barstone doesn’t. Evidently he loves you.”

“He may save himself the trouble. I wouldn’t marry him if he was made of gold. A silly thing who only talks of dogs and horses.”

“And of the union of hearts,” laughed Gilbert, relieved to find that he had no rival in his friend.

“Isn’t it nonsense?” said Fay, with supreme disdain. “I don’t understand half he says. But then I’m not in love. Have you ever been in love, Mr. Tresham?”

“Well, yes, I suppose so,” said Gilbert, still keeping his eyes on the ground, fearful lest they should betray him. “I’ve been in love at least a dozen times.”

“Oh, you wicked person! What does it feel like?”

“I can hardly explain.”

“Do you feel worn and anguished?” asked Fay, with great intensity. “Do you refuse your meals, and groan by night? Do you walk under her window and say your heart is broken?”

Notwithstanding his feelings, Gilbert could not help laughing at the picture of love drawn by this unsophisticated girl. Evidently Miss Harley had studied surreptitious novels at school, and was imbued with sentiment.

“No! I was never so bad as that,” he said, laughing. “I don’t think men make fools of themselves now-adays.”

“I don’t call it making a fool of oneself,” cried Miss Harley indignantly; “I think it is beautiful. How hard-hearted you are, Mr. Tresham—you would never die for a woman. Oh, how I wish some one would die for me!”

“You wouldn’t like that surely!”

“Yes, I would. If he pined for my love and I refused him, and he went to India, and died with his face to the foe, and my name on his lips. Beautiful!”

“Very!—for you; but rather hard on the man. But why not ask Barstone to die for you?”

“He wouldn’t!” admitted Fay, with great scorn; “he’s too fond of living. Now don’t laugh at me, Mr. Tresham, or I shall be angry.”

“I won’t laugh. You have my sincerest sympathy. But, see, here comes Felix. He looks tired out with play. Come, Felix, and sit down here,” added Gilbert quietly. “You must rest for a time. It is not wise for you to exhaust yourself.”

Without a word Felix, who was pale with weariness, slid down on the grass, and laid his head on Fay’s knee with a contented sigh.

“Are you tired, dear?” she said, smoothing his hair with gentle fingers.

“Very. Tell me a story, Fay.”

“I am not good at stories. Ask Mr. Tresham.”

“Tell me a story, Mr. Tresham,” said Felix, in an eager tone—“about the Romans, you know. The three who kept the bridge.”

“I don’t feel inclined to tell stories,” replied Gilbert, yawning. “Suppose Miss Fay gives us the history of ‘The Priory.’ ”

“Ah, you are thinking of the west wing.”

“Yes; I am anxious to hear the legend connected with it.”

Fay expressed her willingness to relate the tale, and was about to begin, when her father walked feebly across the lawn. He looked pale and ill, almost like a shadow in the bright sunshine, and seated himself on the seat by Fay without a word.

In the distance hovered Jasper, anxiously looking after his master. Had the dumb man known what would be the consequence of that interview, he would never have let Harley join the trio under the oaks. But no one knew the danger, no one saw the shadow in the bright sunshine. To all appearances the four were happy, but their conversation sowed the seeds of future danger, their careless words were pregnant with coming terrors. With characteristic irony, Fate brought them together to weave the web of their lives, and she must have laughed grimly at their fancied security. Only the dumb man was fearful of the future; but he had no power to stay the hand of Fate.

“I was just about to tell a story, papa,” said Fay, seeing that Mr. Harley made no attempt to explain his presence. “I hope you do not mind?”

“Mind, child,” replied her father, raising his eyebrows. “Why should I mind?”

“It is the Legend of the West Wing.”

“Oh, Mr. Tresham, would you kindly place that pillow at the back of my head? Don’t you think Felix had better go away?”

“Papa!” cried Felix, in a tearful voice, “don’t send me away. I want to hear the story.”

“It will make you dream; it is not a healthy story. What do you think, Mr. Tresham?”

“I hardly know, sir,” said Gilbert frankly. “Felix must hear the legend some time or another, so why not now? Besides, he is a brave boy, and doesn’t believe in ghosts.”

“He’ll believe in this one,” said Fay significantly, “in the ghost of the White Prior.”

“That sounds interesting,” observed Harley, leaning back and closing his eyes. “Go on, Fay; freeze the blood in our veins.”

“Oh, the story isn’t so ghostly as all that, papa. I dare say you know it.”

“Certainly I have heard some talk of such nonsense. But as I have never seen the ghost myself I don’t believe in it. Pure invention, my dear child. All these old houses have their spectre. It adds to their value in the nineteenth century.”

“The story, Fay! the story,” cried Felix, weary of his father’s speeches.

Harley shrugged his shoulders, and patted the boy’s shoulder in playful remonstrance at the interruption. Then he settled himself to hear the story, and signed to Fay that she should begin, an invitation at once responded to by that impatient young lady.

“In the reign of Henry VIII. this was a celebrated Priory,” she began, with due solemnity, “wealthy and holy. People came from far and near to worship in its chapel, when permitted to do so by the good monks.”

“Oh!” interjected Mr. Harley, “the discipline must have been very lax if the outside world was permitted to set foot in the monastic chapel.”

“It was only permitted on rare occasions,” responded Fay gravely. “No woman was allowed to enter the chapel, but sick men came to pray here that they might be cured of their ills. Their prayers were always answered, and so the Priory obtained a great reputation and gained much wealth. The chapel is in the west wing, with the chancel window overlooking the river.”

“Indeed,” said Gilbert, starting to his feet and looking at the range of windows. “I suppose you mean the lower end. It does not look like a chapel. The windows—”

“Were all removed,” interrupted Fay grandly. “This place was given to one of my ancestors by Henry VIII., and he being a zealous Protestant destroyed all the relics of popery. Half of the west wing consists of chambers and store-rooms, but the lower half is the chapel I speak of. Only the church window is left. We will go and see it shortly.”

“Indeed, you’ll do no such thing,” said Mr. Harley sharply. “I won’t have any one set foot in the west wing. It’s all dirt and cobwebs, and is better left alone. Go on with your story, Fay. I have not yet heard a word of the White Prior.”

The girl was rather discomfited by her father’s interruption, which seemed to astonish her considerably. As a rule Harley was silent and easy-going, so it was extraordinary that he should assert his authority so unexpectedly in so trifling a matter. Gilbert marvelled at the peremptory manner of the man, but discreetly refrained from interposing a remark. He was glad to notice that Felix, worn out by play and the heat, had fallen asleep, and so was likely to lose the gist of the story. It was not wise that a lad of so fanciful a temperament should hear such tales, and Gilbert had already regretted that he had not sent him away. Now his sleep answered the same purpose.

“The White Prior,” said Fay, when she recovered her composure, “lived in the reign of the seventh Henry. His name was Simon Inger, and he was far in advance of his age in the knowledge of medicine. So many cures were wrought in the chapel during his rule that the monks of a neighbouring convent spread the report that Prior Inger had dealings with the Evil One. I forgot to say that the monks belonged to the Dominican Order, and were white friars. Hence the nickname given to Inger of ‘The White Prior.’ He was given to wandering about the grounds at night, and to passing long hours in the chapel. Sometimes he went abroad and was seen gliding about the lanes like a ghost. He repaired to Marlow on occasions, and there attending to sick folk wrought his cures. For the rest he was a silent man, greatly given to penance. Under his sway the Priory grew famous, and the neighbouring monasteries became jealous. For this reason the story that Prior Inger had dealings with the Evil One was whispered abroad.”

“What a dreary creature,” yawned Harley; “a man without human feelings.”

“Oh, but indeed he was very human,” continued Fay eagerly; “before he entered Holy Orders he was a married man.”

“That is strange,” said Gilbert reflectively. “In those days it was not usual for married men to turn monks. What did his wife say?”

“She was dead, Mr. Tresham. In his young days the White Prior lived in London, and then gave himself up to study. He met with a noble lady and made her his wife, but she died two years after the marriage, leaving him twins, a boy and a girl.”

“Twins,” laughed Harley, “what a ridiculous story! Go on, my dear. This is becoming interesting.”

“Grieved at the loss of his wife, Inger gave up his possessions to a distant relative, on condition that he brought up the children. Then he retired to this monastery, where his brilliant talents soon made him Prior. On entering these walls he surrendered all interest in the world, and heard nothing of his children. They were dead to him, and he to them. Here he was known only as the White Prior, a clever man who was reported to have dealings with the Enemy of Mankind.”

“That was always the fate of cleverness in those days,” said Gilbert idly.

“Yes. For a long time Prior Inger did not take any notice of the scandal, but at last it became so great that there was talk of having him tried and burnt as a sorcerer. Filled with anger at this unjust persecution Inger determined to punish his enemies and to assert his innocence. He found that the brethren of a neighbouring monastery came here by night to spy out his doings. Up yonder,” said Fay, pointing to a high window in the centre of the west wing, “Prior Inger had his study, and there passed long nights in making experiments in medicine, and in studying learned books. One night while thus employed he saw a face at the window, and knew that he was being watched by his enemies from the other monastery, with a view to securing the proof of his guilt. Filled with rage he dashed open the window and precipitated the watching monk to the ground. Then he descended and tried to find him. But the monk had escaped, and only after a long search did Inger see him starting down to the river, there intending to swim across and regain his own monastery.”

“This is very exciting,” said Harley satirically; “quite in the style of Dumas. Well, did your Prior catch the spy?”

“Yes. He seized him as he was stepping into the water, as he was determined to take him prisoner and show up his enemies. The spy struggled, and Inger lost his temper. After a fearful fight, the Prior strangled the spy. Then he knelt down to look at the dead man’s face. It was his son.”

“His son,” exclaimed Tresham in surprise; “what a dramatic situation. But how came the son to spy on his father?”

“He did not know Prior Inger was his father,” explained Fay, delighted at the effect of the story. “It appeared that the relation who brought up the twins gave them his own name, and told them nothing about their parents. Both were quite ignorant that their father was the White Prior. When they grew up the boy, following in his father’s footsteps, was filled with religious zeal, and became a monk, in the monastery where the scandal about the White Prior was started. He, hearing that Inger was a sorcerer, determined to learn the truth and to expose him. Therefore he watched night after night for proofs till Inger caught and killed him.”

“How did the Prior recognize his son, after so many years?”

“By the likeness to his dead wife.”

“Humph! and by that time the wife must have been dead at least twenty or more years,” said Harley sceptically. “A very pretty story, but untrue.”

“Of course it is only legendary,” interposed Gilbert hastily, seeing that Fay was offended. “Well, Miss Harley, and what did Inger do when he recognized his son?”

“He was struck with horror at his crime, and flung himself into the river. His body was found the next day with that of his victim, and there was a great scandal over the matter. Eventually it died away, and the pair were buried, but the relationship between them never came to light, as the distant relation who had brought up the boy was dead. But Inger’s name was erased from the list of Priors for sorcery and murder, and it is on this account that his ghost is said to haunt the west wing. It flits about trying to find the books of the monastery, so as to once more inscribe his name in the list of Priors.”

“A silly ghost,” scoffed Harley. “Doesn’t it know that the monastery is a thing of the past? I gave your spectre credit for more sense.”

“What about the daughter?” asked Tresham, when Fay did not respond to her father’s jest.

“She married my ancestor Aylmer Harley, and it was on account of this marriage that she asked the King to give him this Priory where Inger had rooms.”

“Oh! then Dame Harley found out that Inger was her father.”

“Yes; long afterwards. Some papers were found which gave the whole story of the birth, and knowing the tragedy here, all things were made clear. But the White Prior still continues to haunt the west wing.”

“West rubbish!” said Harley angrily.

“It is not rubbish, papa,” said Fay obstinately. “You can see the light he carries flitting from room to room at midnight.”

“I saw that myself,” cried Gilbert, with a start; “but of course it was one of the servants.”

“Very likely,” said Harley negligently, “though I have forbidden the servants to go near the west wing. I don’t wish to encourage superstition. Of course there is no ghost.”

“Papa,” said Fay solemnly, “I have seen it.”

Harley started out of his chair in angry astonishment.

“You, child! Don’t be foolish!”

“I did see it, papa. Last year when you went abroad I came out here late at night as I could not sleep, and I saw the White Prior enter the door of the chapel.”

“I tell you it’s nonsense,” cried Harley, in an excited tone. “That door hasn’t been open for years and years; it is nailed up. You dreamed it, child.”

“I don’t think so.”

“Then it must have been an hallucination. Don’t repeat this nonsense to any one, Fay. I am glad Felix did not hear your story. It would frighten the poor child into hysterics. I forbid you to go near the west wing, or to say a word about the White Prior.”

By this time Harley had completely lost his temper, and was so agitated that he trembled with rage and could hardly form his words. Noticing his behaviour Jasper ran across the lawn and took his master by the arm. The touch seemed to calm Harley, for he recovered his composure in some part, and submitted to be led back to the house by the attentive valet. He paused, however, to give Fay a last warning.

“If you say a word more about the White Prior,” said he sternly, “you shall leave the house.”

June 30th.—In looking over my diary, I find that I have noted my intention of asking who was in the west wing at midnight on the 24th inst. I did inquire, but I learned nothing. The servants denied that any one of them had been there, saying that by Mr. Harley’s orders the west wing was locked up, and they were forbidden to enter it. I found that the belief in the ghost of the White Prior was universal both in the Priory and the neighbourhood, so I expect no one will care to enter the disused chapel after dark. Superstition is a surer preventive of any curiosity on their part about the west wing than Mr. Harley’s orders. It is extraordinary how the servants believed in the ghost. The nineteenth century has not done much for them in the way of enlightenment.

To-day I heard the legend of “The White Prior” from the lips of Fay, and was much interested therein, both on account of the story and the story-teller. She certainly related it in a very dramatic manner; too much so for her father’s self-control, for he spoke angrily to her when it was finished. Why he should lose his temper over such a trifle I cannot imagine; the more so as he is sceptical of the supernatural and laughs the legend to scorn. It may be that he does not wish the Priory to become notorious as a haunted house; but if this is his objection he is too late in making it by over a hundred years. The legend is common property in the neighbourhood, and has been told by the old wives on winter evenings for generations. I have no doubt that the tale loses nothing by re-telling, and that every new narrator adds if possible to the gloom and horror of the legend. It is decidedly dramatic, and full of weird fascination. With such material to my hand it would be an oversight on my part not to make use of it for a story. But this I shall not do till I leave the Priory, as Mr. Harley might object to my giving such a ghostly tradition to the world.

I cannot help thinking that there is something more than the legend of the White Prior which makes him so firm in his refusal to throw open the west wing. If it is only the ghost, why does he not pull the building down? It is never inhabited, it is falling to ruin, it is no use to anybody, and though its destruction would destroy the symmetry of the quadrangle, yet were I in Mr. Harley’s place I should decidedly raze it to the ground. In no other way will he rid his house of the horror. I suggested as much to him at dinner, but he frowned on the proposal, and gave me politely to understand that the idea was disagreeable to him. Even Jasper, who waited at table, seemed angered at my proposing so daring a thing.

I don’t like Jasper, and on his part I feel certain that he has taken a violent dislike to me. My midnight vigils have become known to him, and he greatly resents my curiosity. In my bedroom yesterday I found a second card inscribed “Don’t watch the west wing,” and when I spoke to Mr. Harley about pulling it down Jasper shook his head angrily and nearly upset a sauce-boat over my clothes. Whatever the mystery connected with the west wing may be, he is as nearly concerned in it as his master, and objects to any mention of that part of the house. Needless to say, these objections only rouse my curiosity the more, and I am determined on some future occasion to visit the chapel, and to go through the narrow little chambers where Fay tells me the monks slept in the old days.

Fay! Every time I write that dear name my hand trembles. I have known her scarcely eight weeks, yet already I am fathoms deep in love. Had any one prophesied my fall, I should have laughed in his face; but the passion has nevertheless come to me. I am in love with an Undine, inasmuch as she has no soul and cannot comprehend my feelings. It is true that she talks of marriage, and of broken hearts and silly vows, but all this is but the folly of girlhood. She is as innocent of true knowledge as a child. And indeed, despite her eighteen years, she is only a child. When love enters her heart then will she change to woman; but the transformation is yet far off. She is friendly with me, she likes to be in my company, but beyond that, nothing more. Love-making is Greek to her, so, fearful of frightening her, I keep my soul out of my eyes. It is a hard task but necessary, and some day she may grow to love me. Of one thing I am certain, I have no rival.

July 10th.—Felix is progressing very well with his studies, and is much healthier, thanks to open-air exercise, than he ever was before. By pursuing my present course I hope to make him reasonably stronger—but, alas! the poor child is so sickly and worn out that I fear he will not live long. His body is weak, his brain is too active, and I have to be very judicious in my teaching. Did I let him, he would pore over books all day, and sometimes it is difficult to induce him to leave the house. In this he resembles his father, who remains shut up in his room of mirrors all day—and only occasionally emerges for a gentle stroll on the arm of Jasper. It was a sin for such a man to marry and beget children. I have heard nothing of the late Mrs. Harley, but she must have been a splendid specimen of womanhood, for I feel sure that Fay takes after her. I can hardly believe that Harley, frail and peevish, is her father. Concerning the paternity of Felix there is no doubt. He is like his father in every respect, as weak, as sickly, and as irritable. The poor child is subject to somnambulism, for hearing a step in the corridor last night I went out and found Felix walking down-stairs. At once I took him back to his bed, and since then I have locked the door every night, so that he may not indulge in these midnight peregrinations. I am glad he did not hear the legend of the White Prior, for his brain is too excitable as it is, and a severe fright might unhinge what little mind he has. Felix is a standing example of the curse of heredity.

July 20th.—At last I have succeeded in exploring the west wing without the knowledge of any one. To find the ghost of the White Prior I resolved to make the attempt; at midnight I carried out my resolve, and—I am as wise as I was before. The mystery is deepened instead of being cleared up, and I am more suspicious of Jasper than ever.

To go back to the beginning of my adventure. I first examined the west wing from the outside, in order to see how I could effect an entry without being seen by that watchful mute. Within, all doors leading from the main building to the west wing are built up save one; and that is carefully locked, the key being in Mr. Harley’s possession. Clearly there was no chance of getting in there, so I strolled down under the oaks and examined the walls. Two ranges of small windows come half-way down to the river, and give light to the numerous chambers or cells formerly occupied by the monks. Thence eight large windows, extending almost from roof to ground, illuminate the disused chapel. The pointed shape and the delicate stonework of these were destroyed by Aylmer Harley the iconoclast, and some are filled with common glass set in rough leaden frames, while others are boarded up so as to exclude the light altogether from the interior. Unless I tore down the boards or broke the glass, there was no hope of getting inside, and as doing so meant discovery by Jasper, and consequently by Mr. Harley, I dismissed the idea. True there is a door, but it is nailed up, and impossible to move. Evidently all precautions had been taken to shut up the west wing. I wonder why? That is the reason I explored it.

On the river a mighty window overlooks the water, the sole remnant of the ecclesiastical glory of the chapel. Three fluted columns spring upwards into lance-shape forms, and above, the stonework is twisted and turned this way and that into a mass of delicate tracery more like lacework than carved stone. The upper part is filled with painted glass, so also is a goodly portion between the lower columns; but on the right—looking from the river—the whole of the lower central pane is broken, and as it is sufficiently screened from the stream by a mighty oak, no attempt has been made to mend it. Jealous as the Harleys are of their mystery, they never dream for a moment that any one would espy this weak point in their armour, or, urged by curiosity, would take advantage of it. They are wrong, for, waiting until midnight, I made my entry by the broken pane.

I found time to go to Marlow and purchase a bull’s-eye lantern, so I could shut off the light at a moment’s notice. Wrapped in my overcoat, and carrying the lantern strapped round my waist, I waited until the stable clock struck twelve; then deeming that all was safe I crept down-stairs, let myself out by one of the drawing-room windows, and so gained the shelter of the oak walk. I must admit that I felt guilty and intrusive, for I had no right to penetrate the secrets of my employer. But so singular is his behaviour about the west wing, and so heavy is the mystery which hangs over it, that I cannot forbear satisfying my curiosity. Nine men out of ten would do the same in my place.

All was dark, and I had no difficulty in getting to the tree which hid the broken window. Up it I scrambled, and swung myself on to the stonework. Then I turned on the light and saw that I could easily drop on to the floor of the church. The next moment I stood within, and waited with bated breath for a moment or so, to assure myself that all was well. Not a sound could I hear, and standing there in the black gloom of the church, I faltered for a moment in my purpose. Who knows what horrible things I might meet with in that darkness, into what pits I might fall, or what dangers I might encounter? I own that I felt afraid for at least two minutes.

At this moment the moon emerged from behind a cloud, and poured in her light through the windows on the left. The great blank spaces of glass, only boarded up at the lower end, admitted the light freely, and I caught a glimpse of the interior of the building. Two ranges of pillars went down either side from the chancel, and vanished in the darkness of the roof. The floor of the church was of marble, and broad steps descended to the body of the chapel. At the back of me, under the window, the high altar, stripped of all adornments, yet remained, and in the near wall I could see the niches wherein the priests sat during the service of the church. The whole place was bare and black in appearance.

Taking all this in at a glance, I moved down the church, throwing my light before me. At the end I came on a broad flight of steps which led up to a wide door. This stood open, and I passed into a dark corridor lighted dimly from the roof by skylights. At the end of this again, the staircase branched to right and left, leading to the upper cells, while on either side I could see the lower ones, small rooms, lighted each by its window. Ascending the stairs, I found a door at the top against the dividing wall, and had no doubt that it led to the main body of the mansion. So far I knew the whole construction of the west wing.

The cells were all unfurnished, at least those were into which I looked, so seeing nothing to attract my attention I returned to the chapel. Just as I got down on to the main floor, I heard the creaking of a door, and at once shutting off my light I slipped behind a pillar to watch. To my surprise the door opening on to the quadrangle, which Harley said was nailed up, was pushed wide open, and a man entered with a bundle on his shoulder. Closing the door again, he moved into the principal aisle of the church, and set down his bundle in full moonlight. It was Jasper, the dumb man. Dumb! I heard him speak!

Producing a candle he lighted it carefully, muttering to himself the while. Hidden in the darkness of the pillar I was safe from observation, and heard him speak.

“Aye, aye,” he muttered, again hoisting the bundle on to his shoulders. “This is the tenth time. If it wasn’t for old Jasper there would be murder done. But she sha’n’t die if I can help it. Aye, that she sha’n’t.”

Thus talking to himself he advanced towards the steps, and disappeared into the corridor, where I saw his light twinkling like a star in the darkness. As for myself I had heard quite enough, and resolved to remove myself from so dangerous a neighbourhood. Fortunately there was no necessity to get out through the window, for he had not locked the door. In a moment I had slipped outside and drawn it to, then walking quickly up to the terrace under the shadow of the trees I gained the drawing-room window, and so re-entered my chamber. Once there I sat down to consider what I had discovered. The shock of finding that Jasper was feigning dumbness was terrible. What could be the reason of his behaviour? What was he doing in the church with a bundle? Why did he talk about murder, and refer to a woman in connection therewith? These were the questions that I asked myself, but in no way could I answer them. The vague mystery that overhung the west wing had suddenly assumed a tangible shape. There was some terrible deed about to be done. I wondered if Harley knew of Jasper’s movements; if he was aware that the man could talk. I could not say. I was helpless to further solve the mystery, and learn what it all meant.

The word murder used by Jasper struck a chill into my being, and I felt afraid as to who was to be murdered. Jasper mentioned a woman. What woman? I cannot answer these questions, so I must stop. Time alone will enable me to find out the truth. Is it to be found in the past history of the Harley family? Who can tell?

“Well, Tresham,” said Sir Percy Barstone, when he was comfortably seated in an arm-chair, “what do you think of your new employment?”

They were chatting in Gilbert’s sitting-room, and the clock had just struck eleven. Barstone had arrived at his country-house on the previous day, and, anxious to know how Tresham liked the appointment which he had been instrumental in procuring for him, had called at the Priory that afternoon. Perhaps a desire to see Fay had also something to do with the visit.

Harley, with whom the young man was a great favourite on account of his cheerful disposition, insisted that he should stay to dinner, so after apologizing for his clothes, Barstone accepted the invitation. All that evening he basked in the sunshine of Fay’s smiles, and when reluctantly taken to the library by Harley, he sadly bade her good-night. He would much rather have stayed in the drawing-room listening to the girl’s merry chatter, than have hearkened to Harley’s prosing about first editions and black-letter folios, but could not refuse to obey his host, and so left paradise. Luckily Harley was irritable and weary, so he did not detain either his guest or the tutor long in his sanctum; thus it was they found themselves seated up-stairs for a final chat before parting for the night.

Felix, in accordance with Gilbert’s wise rule, had retired to bed at nine o’clock, and Fay had followed his example: therefore, Harley having dismissed him, Barstone became dependent upon Gilbert for company. He was not sorry, as there were many things he wished to ask his friend, prominent among which was the question above set forth. As a matter of fact, Barstone was rather jealous of Tresham’s good looks, lest they should make an impression on Fay. He wanted the young lady for himself, and began to question the wisdom of introducing a handsome and clever man to her notice. All of which showed that he had not yet realized that Fay was still a child, and ignorant of many things.

“How do you like your appointment, Tresham?” he said for the second time, seeing that his friend did not answer.

“I am just thinking,” replied Gilbert, sedately drawing at his pipe.

“You are just thinking,” echoed Barstone, running his fingers through his light hair. “Good gracious, man, does it require thinking? You are in a delightful old country-house, living with a sybarite who gives good dinners. You have plenty of time for your writing, and see a pretty girl every hour of the day. What more do—”

“That’s just it,” interrupted Gilbert, laughing. “The pretty girl is my trouble. I don’t want to be a traitor to you, Barstone, as I saw from your letter that your affections were set on Miss Harley. But I—”

“Say no more. You’re in love with her.”

“I’m afraid so. I can’t help myself. It came so suddenly, so strongly.”