Amazon - Website

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

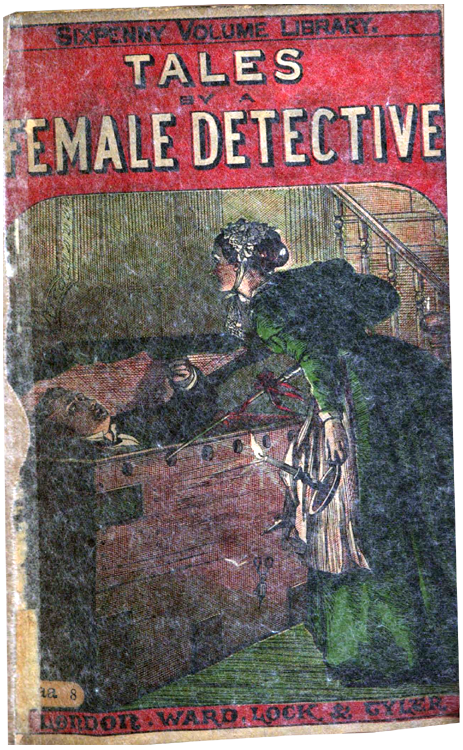

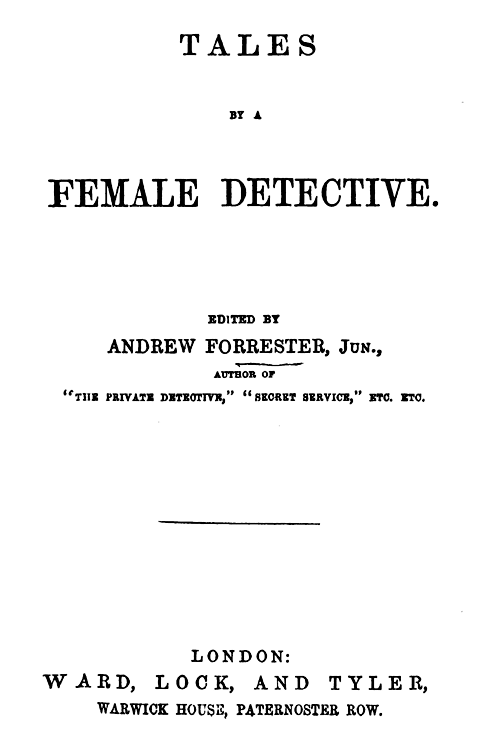

Title: Tales by a Female Detective Author: Andrew Forrester, Jun. * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1901181h.html Language: English Date first posted: November 2019 Most recent update: November 2019 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

The Unraveled Mystery

The Unknown Weapon

We, meaning thereby society, are frequently in the habit of looking at a successful man, and while surveying him, think how fortunate he has found life, how chances have opened up to him, and how lucky he has been in drawing so many prizes.

We do not, or we will not, see the blanks which he may have also drawn. We look at his success, thinking of our own want of victories, shut our eyes to his failures, and envy his good fortune instead of emulating his industry. For my part I believe that no position or success comes without that personal hard work which is the medium of genius. I never will believe in luck.

When this habit of looking at success and shutting our eyes to failure is exercised in reference, not to a single individual, but to a body, the danger of coming to a wrong conclusion is very much increased.

This argument is very potent in its application to the work of the detective. Because there are many capital cases on record in which the detective has been the mainspring, people generally come to the conclusion that the detective force is made up of individuals of more than the average power of intellect and sagacity.

Just as the successful man in any profession says nothing about his failures, and allows his successes to speak for themselves, so the detective force experiences no desire to publish its failures, while in reference to successes detectives are always ready to supply the reporter with the very latest particulars.

In fact, the public see the right side only of the police embroidery, and have no idea what a complication of mistakes and broken threads there are on the wrong.

Nay, indeed, the public in their admiration of the public successes of the detective force very generously forget their public failures, which in many instances are atrocious.

To what cause this amiability can be attributed it is perhaps impossible to say, but there is a great probability that it arises from the fact that the public have generally looked upon the body as a great public safeguard—an association great at preventing crime.

Be this as it may, it is certain that the detective force is certainly as far from perfect as any ordinary legal organization in England.

But the reader may ask why I commit myself to this statement, damaging as it is to my profession.

My answer is this, that in my recent days such a parliamentary inquiry (of a very brief nature, it must be conceded) has been made into the uses and customs of the detective force, as must have led the public to believe that this power is really a formidable one, as it affects not only the criminal world but society in general.

It had appeared as though the English detectives were in the habit of prying into private life, and as though no citizen were free from a system of spydom, which if it existed would be intolerable, but which has an existence only in imagination.

It is a great pity that the minister who replied to the inquiry should have so faintly shown that the complaint was faint, if not altogether groundless.

I do not suppose the public will believe me with any great amount of faith, and simply because I am an interested party; yet I venture to assert that the detective forces as a body are weak; that they fail in the majority of the cases brought under their supervision; and finally, that frequently their most successful cases have been brought to perfection, not by their own unaided endeavours so much as by the use of facts, frequently stated anonymously, and to which they make no reference in finally giving their evidence. This evidence starts from the statement, “from information I received.” Those few words frequently enclose the secret which led to all the after operations which the detective deploys in description, and without which secret his evidence would never have been given at all.

The public, especially that public who have experienced any pressure of the continental system of police, and who shudder at the remembrance of the institution, need have no fear that such a state of things municipal can ever exist in England. It could not be attempted as the force is organized, and it could not meet with success were the constitution of the detective system invigorated, and in its reformed character pressed upon English society, for it would be detected at once as unconstitutional, and resented accordingly.

With these remarks I will to the statement I have to make concerning my part, that of a female detective, in the attempt to elucidate a criminal mystery which has never been cleared up, which from the mode in which it was dealt with, ran little chance of being discovered, and which will now never be explained.

The simple facts of the case, and necessary to be known, are these:—

One morning, a Thames boatman found a carpet-bag resting on the abutment of an arch of one of the Thames bridges. This treasure-trove being opened, was found to contain fragments of a human body—no head.

The matter was put into the hands of the police, an inquiry was made, and nothing came of it.

This result was very natural.

There was little or no intellect exercised in relation to the case. Facts were collected, but the deductions that might have been drawn from them were not made, simply because the right men were not set to work to—to sort them, if I may be allowed that expression.

The elucidation, as offered by me at the time, and which was in no way acted upon, was due—I confess it at first starting—not to myself, but to a gentleman who put me in possession of the means of submitting my ultimate theory of the case to the proper authorities.

I was seated one night, studying a simple case enough, but which called for some plotting, when a gentleman applied to see me, with whom I was quite willing to have an interview, though I did not even remotely recognise the name on the card which was sent in to me.

As of course I am not permitted to publish his name, and as a false one would be useless, I will call him Y—.

He told me, in a few clear, curt words, very much like those of a detective high in office, and who has attained his position by his own will, that he knew I was a detective, and wanted to consult with me.

“Oh, very well, if I am a detective, you can consult with me. You have only yourself to please.”

He then at once said that he had a theory of the Bridge mystery, as he called it and as I will call it, and that he wanted this theory brought under the consideration of the people at Scotland Yard.

So far I was cautious, asking him to speak.

He did so, and I may say at once that at the end of a minute I threw off the reserve I had maintained and became frank and outspoken with my visitor.

I will not here reproduce his words, because if I did so I should afterwards have to go through them in order to interpolate my own additions, corrections, or excisions.

It is perhaps sufficient to say that his entire theory was based upon grounds relating to his profession as a medical man. Therefore, whenever a statement is made in the following narrative which smacks of the surgery, the reader may fairly lay its origin to Y—; while, on the other hand, the generality of the conclusions drawn from these facts are due to myself.

I shall therefore put the conversations we had at various times in the shape of a perfected history of the whole of them, with the final additions and suggestions in their proper places, though they may have occurred at the very commencement of the argument.

As our statement stood, as it was submitted to the authorities, so now it is laid before the public, official form and unnecessary details alone being excised.

1. The mutilated fragments did not when placed together form anything like an entire body, and the head was wanting.

The first fact which struck the medical man was this, that the dissection had been effected, if not with learning, at least with knowledge. The severances were not jagged, and apparently the joints of the body had not been guessed at. The knife had been used with some knowledge of anatomy.

The inference to be drawn from these facts was this, that whoever the murderer or homicide might be, either he or an accessory, either at or after the fact, was inferentially an educated man, from the simple discovery that there was evidence he knew something of a profession (surgery) which presupposes education.

Now, it is an ordinary rule, in cases of murder where there are two or more criminals, that these are of a class.

That is to say, you rarely find educated men (I am referring here more generally to England) combine with uneducated men in committing crime. It stands evident that criminals in combination presupposes companionship. This assertion accepted, or allowed to stand for the sake of argument, it then has to be considered that all companionship generally maintains the one condition of equality. This generality has gained for itself a proverb, a sure evidence of most widely-extended observation, which runs—“Birds of a feather flock together.”

Very well. Now, where do we stand in reference to the Bridge case, while accepting or allowing the above suppositions?

We arrive at this conclusion:—

That the state of the mutilated fragments leads to the belief that men of some education were the murderers.

2. The state of the tissue of the flesh of the mutitilated fragments showed that the murder had been committed by the use of the knife.

This conclusion was very easily arrived at.

There is no need to inform the public that the blood circulates through the whole system of veins and arteries in about three minutes, or that nothing will prevent blood from coagulating almost immediately it has left the veins. To talk of streams of blood is to speak absurdly.

If, therefore, an artery is cut, and the heart continues to beat for a couple of minutes after the wound is made, the blood will be almost pumped out of the body, and the flesh, after death, will in appearance bear that relation to ordinary flesh that veal does to ordinary beef—a similar process of bleeding having been gone through with the calf, that of exhausting the body of its blood.

What was the conclusion to be drawn from the fact that the fragments showed by their condition that the murdered man had been destroyed by the use of the knife?

The true conclusion stood thus—that he was murdered by foreigners.

For if we examine a hundred consecutive murders and homicides, committed in England by English people, we shall find that the percentage of deaths from the use of the knife is so small as barely to call for observation. Strangling, beating, poisoning (in a minor degree)—these are the modes of murder adopted in England.

The conclusion, then, may stand that the murder was committed by foreigners.

I am aware that against both the conclusions at which I have arrived it might be urged that educated and uneducated men have been engaged in the same crime; and secondly, that murders by the knife are perpetrated in England.

But in all cases of mystery, if they are to be solved at all, it is by accepting probabilities as certainties, so far as acting upon them is concerned.

3. There was further evidence than supposition to show that the remains were those of a foreigner.

This evidence is divided into a couple of branches. The first depends upon the evidence of the pelves, or hip bones, which formed a portion of the fragments; the second upon the evidence of the skin of the fragments.

First—

It may be remarked by any one of experience that there is this distinctive difference between foreigners and Englishmen, and one which may be seen in the Soho district any day—that while the hips of foreigners are wider than those of Englishmen, foreign shoulders are not so broad as English; hence it results that while foreigners, by reason of the contrast, look generally wider at the hips than shoulders, Englishmen, for the greater part, look wider at the shoulders than the hips.

This distinction can best be observed in contrasting French and English, or German and English soldiery. Here you find it so extremely evident as not to admit discussion.

Now, was there any evidence in the fragments to which this comparative international argument could apply?

Yes.

The medical gentleman who examined the fragments deposed that they belonged to a slightly-built man. Then followed this remarkable statement, that the hip bones, or pelves, were extremely large.

The second branch of this evidence, relating to the skin, may now be set out.

The report went on to say that the skin was covered with long, strong, straight black hairs.

Now it is very remarkable that the skin should exhibit those appearances which are usually associated with strength, while the report distinctly sets out that the fragments belonged to a slightly-built man.

It strikes the most ordinary thinker at once that his experience tells him that slight, weakly made men are generally distinguishable for weak and thin hair. Most men at once recognise the force of the poetical description of Samson’s strength lying in his hair.

There is, then, surely something contradictory in the slight build, and the long, strong black hair, if we judge from our ordinary experience. But if we carry our experience beyond the ordinary, if we go into a French or Italian eating-house in the Soho district, it will be found that scarcely a man is to be found who is destitute of strong hair, for the most part black, upon the face. It need not be added that hair thickly growing on the face is presumptive proof that the entire skin possesses that faculty, the palms of the hands and soles of the feet excepted.*

*It should be here again pointed out that it is to the doctor that these physiological remarks are to be attributed.

Now follows another intricate piece of evidence. The hairs are stated to be long, black, and strong—that is to say, black, thick, and without any curl in them.

Any man who, by an hospital experience, has seen many English human beings, will agree with me that the body hair here in England is rarely black, rarely long, and generally with a tendency to curl.

Now, go to the French and Italian cafés already referred to, and it will be found that the beards you shall see are black, very strong, and the hairs individually straight.

The third conclusion stands thus:

That the bones and skin of the fragments point to their having formed a portion of a foreigner rather than an Englishman.

Evidence of the Fragments. The evidence of the fragments, therefore, goes problematically to prove that the murdered man was an educated foreigner, stabbed to death by one or more educated foreigners.

Now, what evidence can be offered which can support this theory?

Much.

In the first place, the complaints of the French Government to England, and the results of those complaints, very evidently show that London is the resting-place of many determined foreigners. In fact, it is a matter beyond all question, that London has at all times been that sanctuary for refugees from which they could not be torn.

Hence London has always been the centre of foreign exiled disaffection.

Then if it can be shown that foreign exiled disaffection is given to assassination, it stands good that we have here in London foreigners who are ready to assassinate.

Experience shows that this tendency to assassinate on the part of foreign malcontents is a common understanding amongst them. There is no need to refer to the attempts upon the life of the Emperor of the French, upon the life of the father of the late King of Naples—there is no need to point out that in the former cases the would-be assassins have lived in London, and have generally set out from London. All required is, to talk of tyranny with the next twenty foreigners you may meet, good, bad, and indifferent. It will be found that the ordinary theory in reference to a tyrant is, not that he shall be overthrown by the will of the people, but by the act of assassination.

This theory is the natural result, possibly, of that absence of power in the people which we English possess. We take credit to ourselves for abhorring assassination in reference to tyrants; but it should never be forgotten that here we have no need of assassination—the mere will of the people (when it is exerted) being quite enough to carry away all opposition.

Once admit assassination as a valuable aid in destroying tyranny, and you recognise by inference its general value as a medium of justice and relief.

Now apply the argument to the treachery of a member of a secret society, and you will comprehend the suggestion that the murdered man was a member of a secret political society, who was either false, or supposed to be false, to the secret society to which he belonged.

The question now arises—are there foreign secret societies established in London?

Have they an existence abroad? Unquestionably. Even here in open England there are a dozen secret societies of a fellowship-like character—Masons, and Foresters, and Odd Fellows, &c. &c.

And if foreigners have secret societies abroad, in spite of the police, why not here, where they have perfect liberty to form as many secret societies as they like?

Where has the money come from which has rigged out various penniless men, and sent them on the Continent to assassinate this or that potentate?

The inference is good that the money is found by secret societarians. Where else could it come from? Exiles personally are not rich; but if twenty economical professors save two pounds a-piece in six months, there is forty pounds to be applied to a purpose.

Is there any solid evidence beyond that of the fragments to suggest that the murdered man was a foreigner? There is.

In the first place, the state of those fragments showed that death had been recent—say, within two days.

Now, was any man missing during those two days who was in any way suggestively identifiable with the dead man?

If so, no application was made to the police.

Now, if the dead man were an Englishman, and all who knew him were not implicated in his death (a most unlikely supposition), it seems pretty evident that the discovery of the murder following so swiftly on the fact, some clue to the mystery must have been gained.

Granted the supposed Englishman had no relations in London (for it must be accepted as certain that the murder was committed in town, it being hardly within the bounds of possibility to suppose that the remains were brought into London to hide)—granted he had no friends, he must have had either servants, landlady, or employers. If any of these had existed, how certain it is that the publicity of the crime would have been followed by some inquiries by some of these people.

Not one was made.

Not any evidence was offered to the police that could for a moment be looked upon as valuable, although it is not perhaps going too far to say that every soul in London who could comprehend the affair had heard of and talked it over within twenty-four hours of its discovery, thanks to the power and extension of the press.*

* I point out as an instance of the late case of poisoning a wife and children in a cab. The culprit was discovered within twenty-four hours of the publication of the crime, and by several people in no way connected with the family in which the catastrophe occured.

But see how thoroughly this absence of all inquiry will fall in with the murdered man having been a foreign refugee resting in this country.

Firstly—these refugees lodge together, and make so free with each other’s lodgings, and visit so frequently and so generally, that an English landlady would have some difficulty in telling who was and who was not her lodger. It would be most unlikely that she would miss a foreigner who had been staying with her foreign lodger some weeks. Hence it might readily happen that a man having no locality with which he could be identified, no suspicion would be aroused by his absence from any particular place.

Then see how this supposed poverty of lodging would accord with a refugee who, broken down by want, might betray his society in order to gain bread, by selling their secrets to his home-police.

Or, on the other hand, he might be an actual police spy, sent by his government to play the refugee and the poverty-stricken wretch, in order the better to penetrate the secrets of conspirators.

Then mark how all chance of recognition is avoided by the absence of the head. In disposing of the fragments, and slinging them over the bridge by means of a rope, it was intended silently to drop the ugly burden into the Thames. The idea of the bag resting on the abutment of the bridge could never have entered into the precautionary measures perfected by the murderers, and yet the necessity of strict secresy was made wonderfully evident in the fact of the head being kept back.

For what purpose? Probably that the chief actors in the murder might be sure of its destruction—perchance that it might be forwarded to the president of a secret society, that the death of the traitor might be proved beyond all dispute.

Another very important line of consideration is the inquiry why such a means of disposing of the remains as that taken was adopted. It will be remarked that the objectionable process of cutting up the body had to be gone through, and that then the dangerous act of carrying or riding with a bag of human remains through the streets to the river had to be effected. And effected in the night time, when it must be notorious to all parties the police are particularly alert in inquiring into the nature of the parcels carried past them. It will frequently happen that the police stop and justifiably examine heavy packages which they find being carried in the streets during the night.

The encountering of all these enormous risks, to say nothing of the fear of interruption during the final act of lowering the carpet-bag, all go to presuppose that the murderers were unable to dispose of the body in any less hazardous manner.

What is the mode in which murderers usually seek to hide the more awful traces of their guilt in the shape of the murdered man? They generally adopt the simplest and safest mode—hiding under the ground.

A body buried ten feet in the ground, even though in the close cellar of a house, would give no warning of the hidden secret. A body buried in quicklime, under similar circumstances, would give no warning, though only four or three feet below the surface.

Burial is the most evident and simplest mode of disposing of a dead body. How is it, then, that the murderers in question did not bury, and ran a series of frightful risks, which resulted in the discovery of the remains?

The answer is obvious—they had no means of burial. In other words, the murder being done in a house where there was no command of the ground floor it was impossible to bury the body, and so it had to be disposed of in some other way. The inference therefore, is, that the occupier of the place was a lodger—not a householder.

Now make inquiries in the Soho district and you will find that refugees rarely become householders. Always hoping, perhaps, to return to their countries, never possibly desirous of taking any step which shall appear to themselves like a settling in a foreign land, it will be found that they prefer lodgings, and that the householders in most of the streets frequented by this sort of people are either English people or foreigners who do not belong to the refugee class, such as Swiss (chiefly) and the world of waiters, who with their savings have gone into foreign housekeeping.

I am aware that there is one good objection to this part of my scheme, in the remark that the murder might have been committed in a house occupied by the murderer or his friends, but that there might be no yard attached, or a yard too much exposed, or that the ground-floor was too publicly in use to admit of time for the removal of the boards, the replacing of the flooring, and the burial of the body.

However, I beg again to urge the doctrine of probabilities. Accepting the theory that it was a murder by foreigners, and not denying the statement that foreign refugees, as a rule, rarely become householders, the probability is greater that the murderers had no ground in which to bury, rather than they had ground at their command, but that circumstances prevented them from using it.

It is true that there is one awkward point in the fact that the bridge selected from which to throw their burden was not so near to the refugee district as the late Suspension Bridge. At first sight it would appear strange that a longer risk should be run by taking the remains to a bridge not the nearest to the scene of the murder. But it must be remembered that the Suspension Bridge had no recesses, while the actual bridge used has many—that the Suspension Bridge was altogether more open and better lit than the other. These suggestions must be taken for what they are worth. I am willing to admit that it still remains extraordinary that the attempt to dispose of the body should have been made at the more distant of the two bridges, and I acknowledge that the apparent advantages of the bridge used over the Suspension do not appear to compensate the extra risk incurred.

Let those who object thoroughly to the whole of this theory, advanced to account for a mystery which has never been cleared up—let them make the most of a weak point.

The probability seems to me that the murdered man was a spy amongst men who, holding to the theory of the justice of assassination, very necessarily recognised its value in relation to a spy in the pay of a tyrant. Nay, to be at once exhaustive in reference to spies, few people will be inclined to deny that the spy, whatever the shape he has taken, has always been dealt with most implacably.

The supposition once accepted that the murderers had no power of burial, the use of the Thames as a hiding place follows almost as a natural consequence. To hide below the water when the earth is not to be opened for the purpose of concealment appears to be a very natural thought. In what other way could the body be so readily disposable?

The Thames offered secresy, the risk of carriage was surmountable; this means therefore of concealment, though it involved danger to those concerned in the work, was far preferable to leaving the remains in the street—a mode which only a madman would adopt.*

* Such a mode was exercised a few months since with several still-born children. Inquiry was set on foot, and the perpetrator of this open mode of disposing of human remains turned out to be a doctor who had suffered so much from delirium tremens that he might be called a madman.

Had the bag not lodged on the abutment of the bridge not one hint of the crime, it is evident, would ever have been made public. Or two or more may have been concerned in this crime, but they all kept their counsel well. Whether this silence was the result of brotherhood or fear it is impossible to say—possibly the latter. The very success of this one murder would intimidate any societarian who contemplated betraying his companions.

There has but to be added to the statement already put before the reader, two facts which, however, call for little or no comment.

1. The toll-keeper at one end of the bridge recognised the carpet-bag as a heavy one he had lifted over his toll-bar during the night.

2. He stated that he did this kindness for a woman whom he afterwards thought must have been a man in woman’s clothing.

I see no value in this evidence.

1. The identification of the bag was of no value.

2. It does not appear that the man remarked upon any peculiarity of the carrier of the bag till after its discovery on the bridge abutment. And therefore his evidence is not reliable.

All I have now to do is to put in form the result I drew from the above theoretic evidence.

The result in question may be put thus:—

Deduction.—That a foreign man, of age, but not aging, was murdered by stabbing by the members of a secret foreign society of educated men which he had betrayed. That this murder was committed by lodgers and most probably on some other floor than the basement, and of a house situated in the Soho district.

A copy of this statement now made to the reader, but somewhat more abridged and technical was forwarded to the authorities—but so far as I have been able to learn it was never accepted as of any value.

The inquiry, as all the world knows, failed.

I do not wonder that it did.

Left in the hands of English police, who set about their work after their ordinary rule, it is evident that if the murder was committed by foreigners, in a foreign colony, there was little chance of discovery.

I believe the chief argument held against me at the time I sent in my report ran as follows: that if my supposition to the effect that the murdered man was a foreign police spy were correct, the publicity given to the discovery of the remains would have led to a communication sooner or later from a foreign prefect of police stating that an officer was missing.

I did not make a reply to the objection, but I could have announced that the French police, for instance, are not at all desirous of advertising their business, and that a French prefect of police would prefer to lose a man, and let the chance of retribution escape, rather than serve justice by admitting that a French political spy had been in London.

The silence of continental police prefects at that time is by no means to be accepted as an evidence that they missed no official who had been sent to England.

The case failed—miserably.

It could not be otherwise.

How would French police succeed, set to work in Bethnalgreen to catch an English murderer?

They would fail—miserably also.

There can be no question about it, to those who have any knowledge of the English police system, and who choose to be candid, that it requires more intellect infused into it. Many of the men are extraordinarily acute and are able to seize facts as they rise to the surface. But they are unable to work out what is below the surface. They work well enough in the light. When once they are in the dark, they walk with their hands open, and stretched out before them.

Had foreign lodging-houses, where frequent numbers of foreigners assemble, been inquired about, had some few perfectly constitutional searches been made, they might have led to the discovery of a fresh blood-stained floor—it being evident that if a spy were fallen upon from behind and stabbed, his blood must have reached the ground and written its tale there.

These blood-stains must still exist if the house in which the murder took place has not been burnt down, but I doubt if ever the police will make an examination of them at this or any other distance of time, owing to the distant date of the crime.

Experience shows that the chances of discovery of a crime are in exact inverse proportion to the time which has elapsed since the murder. Roughly it may be stated that if no clew is obtained within a week from the discovery of a crime, the chances of hunting down the criminal daily become rapidly fewer and fainter.

Let it not be supposed that I am advocating any change in the detective system which would be unconstitutional. Far from it. I am quite sure any unconstitutional remodelment of that force would not be suffered for any length of time to exist—as it was proved by that recent parliamentary protest against an intolerable excess of duty on the part of the police to which I have already referred.

My argument is, that more intellect should be infused into the operation of the police system, that it is impossible routine can always be a match for all shapes of crime, and finally that means should be taken to avoid so much failure as could be openly recorded of the detective police authorities.

Take in point the case I have been mentioning.

What evidence have the public ever read or learnt to show that any other than ordinary measures were taken to clear up any extraordinary crime?

It is clear that while only ordinary measures are in force to detect extraordinary crime, a premium of impunity is offered to the latter description of ill-doing, and one which it is just possible is often pocketed. Be all that as it may, it is certain the Bridge mystery has never been cleared up.

I am about to set out here one of the most remarkable cases which have come under my actual observation.

I will give the particulars, as far as I can, in the form of a narrative.

The scene of the affair lay in a midland county, and on the outskirts of a very rustic and retired village, which has at no time come before the attention of the world.

Here are the exact preliminary facts of the case. Of course I alter names, for as this case is now to become public, and as the inquiries which took place at the time not only ended in disappointment, but by some inexplicable means did not arrest the public curiosity, there can be no wisdom in covering the names and places with such a thin veil of fiction as will allow of the truth being seen below that literary gauze. The names and places here used are wholly fictitious, and in no degree represent or shadow out the actual personages or localities.

The mansion at which the mystery which I am about to analyse took place was the manor-house. while its occupant, the squire of the district, was also the lord of the manor. I will call him Petleigh.

I may at once state here, though the fact did not come to my knowledge till after the catastrophe, that the squire was a thoroughly mean man, with but one other passion than the love of money, and that was a greed for plate.

Every man who has lived with his eyes open has come across human beings who concentrate within themselves the most wonderful contradictions. Here is a man who lives so scampishly that it is a question if ever he earnt an honest shilling, and yet he would firmly believe his moral character would be lost did he enter a theatre; there is an individual who never sent away a creditor or took more than a just commercial discount, while any day in the week he may be arrested upon a charge which would make him a scandal to his family.

So with Squire Petleigh. That he was extremely avaricious there can be no doubt, while his desire for the possession and display of plate was almost a mania.

His silver was quite a tradition in the county. At every meal—and I have heard the meals at Petleighcote were neither abundant nor succulent—enough plate stood upon the table to pay for the feeding of the poor of the whole county for a month. He would eat a mutton chop off silver.

Mr. Petleigh was in parliament, and in the season came up to town, where he had the smallest and most miserable house ever rented by a wealthy county member.

Avaricious, and therefore illiberal, Petleigh would not keep up two establishments; and so, when he came to town for the parliamentary season, he brought with him his country establishment, all the servants composing which were paid but third-class fares up to town.

The domestics I am quite sure, from what I learnt, were far from satisfactory people; a condition of things which was quite natural, seeing that they were not treated well, and were taken on at the lowest possible rate of wages.

The only servitor who remained permanently on the establishment was the housekeeper at the manor-house, Mrs. Quinion.

It was whispered in the neighbourhood that she had been the foster-sister (“and perhaps more”) of the late Mrs. Petleigh; and it was stated with sufficient openness, and I am afraid also with some general amount of chuckling satisfaction, that the squire had been bitten with his lady.

The truth stood that Petleigh had married the daughter of a Liverpool merchant in the great hope of an alliance with her fortune, which at the date of her marriage promised to be large. But cotton commerce, even twenty-five years ago, was a risky business, and to curtail here particulars which are only remotely essential to the absolute comprehension of this narrative, he never had a penny with her, and his wife’s father, who had led a deplorably irregular life, started for America and died there.

Mrs. Petleigh had but one child, Graham Petleigh, and she died when he was about twelve years of age.

During Mrs. Petleigh’s life, the housekeeper at Petleighcote was the foster-sister to whom reference has been made. I myself believe that it would have been more truthful to call Mrs. Quinion the natural sister of the squire’s wife.

Be that as it may, after the lady’s death Mrs. Quinion, in a half-conceded, and after an uncomfortable fashion, became in a measure the actual mistress of Petleighcote.

Possibly the squire was aware of a relationship to his wife at which I have hinted, and was therefore not unready in recognising that it was better she should be in the house than any other woman. For, apart from his avariciousness and his mania for the display of plate, I found beyond all dispute that he was a man of very estimable judgment.

Again, Mrs. Quinion fell in with his avaricious humour. She shaved down his household expenses, and was herself contented with a very moderate remuneration.

From all I learnt, I came to the conclusion that Petleighcote had long been the most uncomfortable house in the county, the display of plate only tending to intensify the general barrenness.

Very few visitors came to the house, and hospitality was unknown; yet, notwithstanding these drawbacks, Petleigh stood very well in the county, and indeed, on the occasion of one or two charitable collections, he had appeared in print with sufficient success.

Those of my readers who live in the country will comprehend the style of the squire’s household when I say that he grudged permission to shoot rabbits on his ground. Whenever possible, all the year round, specimens of that rather tiring food were to be found in Squire Petleigh’s larder. In fact, I learnt that a young curate who remained a short time at Tram (the village), in gentle satire of this cheap system of rations, called Petleighcote the “Warren.”

The son, Graham Petleigh, was brought up in a deplorable style, the father being willing to persuade himself, perhaps, that as he had been disappointed in his hopes of a fortune with the mother, the son did not call for that consideration to which he would have been entitled had the mother brought her husband increased riches. It is certain that the boy roughed life. All the schooling he got was that which could be afforded by a foundation grammar school, which happened fortunately to exist at Tram.

To this establishment he went sometimes, while at others he was off with lads miserably below him in station, upon some expedition which was not perhaps, as a rule, so respectable an employment as studying the humanities.

Evidently the boy was shamefully ill-used; for he was neglected.

By the time he was nineteen or twenty (all these particulars I learnt readily after the catastrophe, for the townsfolk were only too eager to talk of the unfortunate young man)—by the time he was nineteen or twenty, a score of years of neglect bore their fruit. He was ready, beyond any question, for any mad performance. Poaching especially was his delight, perhaps in a great measure because he found it profitable; because, to state the truth, he was kept totally without money, and to this disadvantage he added a second, that of being unable to spread what money he did obtain over any expanse of time.

I have no doubt myself that the depredations on his father’s estate might have with justice been put to his account, and, from the inquiries I made, I am equally free to believe that when any small article of the mass of plate about the premises was missing, that the son knew a good deal more than was satisfactory of the lost valuables.

That Mrs. Quinion, the housekeeper, was extremely devoted to the young man is certain; but the money she received as wages, and whatever private or other means she had, could not cover the demands made upon them by young Graham Petleigh, who certainly spent money, though where it came from was a matter of very great uncertainty.

From the portrait I saw of him, he must have been of a daring, roving, jovial disposition—a youngster not inclined to let duty come between him and his inclinations; one, in short, who would get more out of the world than he would give it.

The plate was carried up to town each year with the establishment, the boxes being under the special guardianship of the butler, who never let them out of his sight between the country and town houses. The man, I have heard, looked forward to those journeys with absolute fear.

From what I learnt, I suppose the convoy of plate boxes numbered well on towards a score.

Graham Petleigh sometimes accompanied his father to town, and at other times was sent to a relative in Cornwall. I believe it suited father and son better that the latter should be packed off to Cornwall in the parliamentary season, for in town the lad necessarily became comparatively expensive—an objection in the eyes of the father, while the son found himself in a world to which, thanks to the education he had received, he was totally unfitted.

Young Petleigh’s passion was horses, and there was not a farmer on the father’s estate, or in the neighbourhood of Tram, who was not plagued for the loan of this or that horse—for the young man had none of his own.

On my part, I believe if the youth had no selfrespect, the want was in a great measure owing to the father having had not any for his son.

I know I need scarcely add, that when a man is passionately fond of horses generally he bets on those quadrupeds.

It did not call for many inquiries to ascertain that young Petleigh had “put” a good deal of money upon horses, and that, as a rule, he had been lucky with them. The young man wanted some excitement, some occupation, and he found it in betting. Have I said that after the young heir was taken from the school he was allowed to run loose? This was the case. I presume the father could not bring his mind to incurring the expense of entering his son at some profession.

Things then at Petleighcote were in this condition; the father neglectful and avaricious; the son careless, neglected, and daily slipping down the ladder of life; and the housekeeper, Mrs. Quinion, saying nothing, doing nothing, but existing, and perhaps showing that she was attached to her foster-sister’s son. She was a woman of much sound and discriminating sense, and it is certain that she expressed herself to the effect that she foresaw the young man was being silently, steadfastly, unceasingly ruined.

All these preliminaries comprehended, I may proceed to the action of this narrative.

It was the 19th of May (the year is unimportant), and early in the morning when the discovery was made, by the gardener to Squire Petleigh—one Tom Brown.

Outside the great hall-door, and huddled together in an extraordinary fashion, the gardener, at half-past five in the morning (a Tuesday), found lying a human form. And when he came to make an examination, he discovered that it was the dead body of the young squire.

Seizing the handle of the great bell, he quickly sounded an alarm, and within a minute the housekeeper herself and the one servant, who together numbered the household which slept at Petleighcote when the squire was in town, stood on the threshold of the open door.

The housekeeper was half-dressed, the servant wench was huddled up in a petticoat and a blanket.

The news spread very rapidly, by means of the gardener’s boy, who, wondering where his master was stopping, came loafing about the house, quickly to find the use of his legs.

“He must have had a fit,” said the housekeeper; and it was a flying message to that effect carried by the boy into the village, which brought the village doctor to the spot in the quickest possible time.

It was then found that the catastrophe was due to no fit.

A very slight examination showed that the young squire had died from a stab caused by a rough iron barb, the metal shaft of which was six inches long, and which still remained in the body.

At the inquest, the medical man deposed that very great force must have been used in thrusting the barb into the body, for one of the ribs had been half severed by the act. The stab given, the barb had evidently been drawn back with the view of extracting it—a purpose which had failed, the flanges of the barb having fixed themselves firmly in the cartilage and tissue about it. It was impossible the deceased could have turned the barb against himself in the manner in which it had been used.

Asked what this barb appeared like, the surgeon was unable to reply. He had never seen such a weapon before. He supposed it had been fixed in a shaft of wood, from which it had been wrenched by the strength with which the barb, after the thrust, had been held by the parts surrounding the wound.

The barb was handed round to the jury, and every man cordially agreed with his neighbour that he had never seen anything of the kind before; it was equally strange to all of them.

The squire, who took the catastrophe with great coolness, gave evidence to the effect that he had seen his son on the morning previous to the discovery of the murder, and about noon—seventeen and a half hours before the catastrophe was discovered. He did not know his son was about to leave town, where he had been staying. He added that he had not missed the young man; his son was in the habit of being his own master, and going where he liked. He could offer no explanation as to why his son had returned to the country, or why the materials found upon him were there. He could offer no explanation in any way about anything connected with the matter.

It was said, as a scandal in Tram, that the squire exhibited no emotion upon giving his evidence, and that when he sat down after his examination he appeared relieved.

Furthermore, it was intimated that upon being called upon to submit to a kind of cross-examination, he appeared to be anxious, and answered the few questions guardedly.

These questions were put by one of the jurymen—a solicitor’s clerk (of some acuteness it was evident), who was the Tram oracle.

It is perhaps necessary for the right understanding of this case, that these questions should be here reported, and their answers also.

They ran as follows:—

“Do you think your son died where he was found?”

“I have formed no opinion.”

“Do you think he had been in your house?”

“Certainly not.”

“Why are you so certain?”

“Because had he entered the house, my housekeeper would have known of his coming.”

“Is your housekeeper here?”

“Yes.”

“Has it been intended that she should be called as a witness?”

“Yes.”

“Do you think your son attempted to break into your house?”

[The reason for this question I will make apparent shortly. By the way, I should, perhaps, here at once explain that I obtained all these particulars of the evidence from the county paper.]

“Do you think your son attempted to break into your house?”

“Why should he?”

“That is not my question. Do you think he attempted to break into your house?”

“No, I do not.”

“You swear that, Mr. Petleigh?”

[By the way, there was no love lost between the squire and the Tram oracle, for the simple reason that not any existed that could be spilt.]

“I do swear it.”

“Do you think there was anybody in the house he wished to visit clandestinely?”

“No.”

“Who were in the house?”

“Mrs. Quinion, my housekeeper, and one servant woman.”

“Is the servant here?”

“Yes.”

“What kind of a woman is she?”

“Really Mr. Mortoun you can see her and judge for yourself.”

“So we can. I am only going to ask one question more.”

“I reserve to myself the decision whether I shall or shall not answer it.”

“I think you will answer it, Mr. Petleigh.”

“It remains, sir, to be seen. Put your question.”

“It is very simple—do you intend to offer a reward for the discovery of the murderer of your son?”

The squire made no reply.

“You have heard my question, Mr. Petleigh.”

“I have.”

“And what is your answer?”

The squire paused for some moments. I should state that I am adding the particulars of the inquest I picked up, or detected if you like better, to the information afforded by the county paper to which I have already referred.

“I refuse to reply,” said the squire.

Mortoun thereupon applied to the coroner for his ruling.

Now it appears evident to me that this juryman had some hidden motive in thus questioning the squire. If this were so, I am free to confess I never discovered it beyond any question of doubt. I may or I may not have hit on his motive. I believe I did.

It is clear that the question Mr. Mortoun urged was badly put, for how could the father decide whether he would offer a reward for the discovery of a murderer who did not legally exist till after the finding of the jury? And indeed it may furthermore be added that this question had no bearing upon the elucidation of the mystery, or at all events it had no apparent bearing upon the facts of the catastrophe.

It is evident that Mr. Mortoun was actuated in all probability by one of two motives, both of which were obscure. One might have been an attempt really to obtain a clue to the murder, the other might have been the endeavour to bring the squire, with whom it has been said he lived bad friends, into disrespect with the county.

The oracle-juryman immediately applied to the coroner, who at once admitted that the question was not pertinent, but nevertheless urged the squire as the question had been put to answer it.

It is evident that the coroner saw the awkward position in which the squire was placed, and spoke as he did in order to enable the squire to come out of the difficulty in the least objectionable manner.

But as I have said, Mr. Petleigh, all his incongruities and faults apart, was a clear-seeing man of a good and clear mind. As I saw the want of consistency in the question, as I read it, so he must have remarked the same failure when it was addressed to him.

For after patiently hearing the coroner to the end of his remarks, Petleigh said, quietly,—

“How can I say I will offer a reward for the discovery of certain murderers when the jury have not yet returned a verdict of murder?”

“But supposing the jury do return such a verdict?” asked Mortoun.

“Why then it will be time for you to ask your question.”

I learnt that the juryman smiled as he bowed and said he was satisfied.

It appears to me that at that point Mr. Mortoun must have either gained that information which fitted in with his theory, or, accepting the lower motive for his question, that he felt he had now sufficiently damaged the squire in the opinion of the county. For the reporters were at work, and every soul present knew that not a word said would escape publication in the county paper.

Mr. Mortoun however was to be worsted within the space of a minute.

“Have you ceased questioning me, gentlemen?” asked the squire.

The coroner bowed, it appeared.

“Then,” continued the squire, “before I sit down—and you will allow me to remain in the room until the inquiry is terminated—I will state that of my own free will which I would not submit to make public upon an illegal and a totally uncalled-for attempt at compulsion. Should the jury bring in a verdict of murder against unknown persons, I shall not offer a reward for the discovery of those alleged murderers.”

“Why not?” asked the coroner, who I learnt afterwards admitted that the question was utterly unpardonable.

“Because,” said Squire Petleigh, “it is quite my opinion that no murder has been committed.”

According to the newspaper report these words were followed by “sensation.”

“No murder?” said the coroner.

“No; the death of the deceased was, I am sure, an accident.”

“What makes you think that, Mr. Petleigh?”

“The nature of the death. Murders are not committed, I should think, in any such extraordinary manner as that by which my son came to his end. I have no more to say.”

“Here,” says the report, “the squire took his seat.”

The next witness called—the gardener who had discovered the body had already been heard, and simply testified to the finding of the body—was Margaret Quinion, the housekeeper.

Her depositions were totally valueless from my point of view, that of the death of the young squire. She stated simply that she had gone to bed at the usual time (about ten) on the previous night, and that Dinah Yarton retired just previously, and to the same room. She heard no noise during the night, was disturbed in no way whatever until the alarm was given by the gardener.

In her turn Mrs. Quinion was now questioned by the solicitor’s clerk, Mr. Mortoun.

“Do you and this—what is her name?—Dinah Yarton; do you and she sleep alone at Petleighcote?”

“Yes—when the family is away.”

“Are you not afraid to do so?”

“No.”

“Why?”

“Why should I be?”

“Well—most women are afraid to sleep in large lonely houses by themselves. Are you not afraid of burglars?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Simply because burglars would find so little at Petleighcote to steal that they would be very foolish to break into the house.”

“But there is a good deal of plate in the house—isn’t there?”

“It all goes up to town with Mr. Petleigh.”

“All, ma’am?”

“Every ounce—as a rule.”

“You say the girl sleeps in your room?”

“In my room.”

“Is she an attractive girl?”

“No.”

“Is she unattractive?”

“You will have an opportunity of judging, for she will be called as a witness, sir.”

“Oh; you don’t think, do you, that there was anything between this young person and your young master?”

“Between Dinah and young Mr. Petleigh?”

“Yes.”

“I think there could hardly be any affair between them, for [here she smiled] they have never seen each other—the girl having come to Petleighcote from the next county only three weeks since, and three months after the family had gone to town.”

“Oh; pray have you not expected your master’s son home recently?”

“I have not expected young Mr. Petleigh home recently—he never comes home when the family is away.”

“Was he not in the habit of coming to Petleighcote unexpectedly?”

“No.”

“You know that for a fact?”

“I know that for a fact.”

“Was the deceased kept without money?”

“I know nothing of the money arrangements between the father and son.”

“Well—do you know that often he wanted money?”

“Really—I decline to answer that question.”

“Well—did he borrow money habitually from you?”

“I decline also to answer that question.”

“You say you heard nothing in the night?”

“Not anything.”

“What did you do when you were alarmed by the gardener in the morning?”

“I am at a loss to understand your question.”

“It is very plain, nevertheless. What was your first act after hearing the catastrophe?”

[After some consideration.] “It is really almost impossible, I should say, upon such terrible occasions as was that, to be able distinctly to say what is one’s first act or words, but I believe the first thing I did, or the first I remember, was to look after Dinah.”

“And why could she not look after herself?”

“Simply because she had fallen into a sort of epileptic fit—to which she is subject—upon seeing the body.”

“Then you can throw no light upon this mysterious affair?”

“No light: all I know of it was the recognition of the body of Mr. Petleigh, junior, in the morning.”

The girl Dinah Yarton was now called, but no sooner did the unfortunate young woman, waiting in the hall of the publichouse at which the inquest was held, hear her name, than she swooped into a fit which totally precluded her from giving any evidence “except,” as the county paper facetiously remarked, “the proof by her screams that her lungs were in a very enviable condition.”

“She will soon recover,” said Mrs. Quinion, “and will be able to give what evidence she can.”

“And what will that be, Mrs. Quinion?” asked the solicitor’s clerk.

“I am not able to say, Mr. Mortoun,” she replied.

The next witness called (and here as an old police-constable I may remark upon the unbusiness-like way in which the witnesses were arranged)—the next witness called was the doctor.

His evidence was as follows, omitting the purely professional points. “I was called to the deceased on Tuesday morning, at near upon six in the morning. I recognized the body as that of Mr. Petleigh junior. Life was quite extinct. He had been dead about seven or eight hours, as well as I could judge. That would bring his death about ten or eleven on the previous night. Death had been caused by a stab, which had penetrated the left lung. The deceased had bled inwardly. The instrument which had caused death had remained in the wound, and stopped what little effusion of blood there would otherwise have been. Deceased literally died from suffocation, the blood leaking into the lungs and filling them. All the other organs of the body were in a healthy condition. The instrument by which death was produced is one with which I have no acquaintance. It is a kind of iron arrow, very roughly made, and with a shaft. It must have been fixed in some kind of handle when it was used, and which must have yielded and loosed the barb when an attempt was made to withdraw it—an attempt which had been made, because I found that one of the flanges of the arrow had caught behind a rib. I repeat that I am totally unacquainted with the instrument with which death was effected. It is remarkably coarse and rough. The deceased might have lived a quarter of a minute after the wound had been inflicted. He would not in all probability have called out. There is no evidence of the least struggle having taken place—not a particle of evidence can I find to show that the deceased had exhibited even any knowledge of danger. And yet, nevertheless, supposing the deceased not to have been asleep at the time of the murder, for murder it undoubtedly was, or manslaughter, he must have seen his assailant, who, from the position of the weapon, must have been more before than behind him. Assuredly the death was the result of either murder or accident, and not the result of suicide, because I will stake my professional reputation that it would be quite impossible for any man to thrust such an instrument into his body with such a force as in this case has been used, as is proved by the cutting of a true bone-formed rib. Nor could a suicide, under such circumstances as those of the present catastrophe, have thrust the dart in the direction which this took. To sum up, it is my opinion that the deceased was murdered without, on his part, any knowledge of the murderer.”

Mr. Mortoun cross-examined the doctor:

To this gentleman’s inquiries he answered willingly.

“Do you think, Dr. Pitcherley, that no blood flowed externally?”

“Of that I am quite sure.”

“How?”

“There were no marks of blood on the clothes.”

“Then the inference stands that no blood stained the place of the murder?”

“Certainly.”

“Then the body may have been brought an immense way, and no spots of blood would form a clue to the road?”

“Not one.”

“Is it your impression that the murder was committed far away from the spot, or near the place where the body was found?”

“This question is one which it is quite out of my power to answer, Mr. Mortoun, my duty here being to give evidence as to my being called to the deceased, and as to the cause of death. But I need not tell you that I have formed my own theory of the catastrophe, and if the jury desire to have it, I am ready to offer it for their consideration.”

Here there was a consultation, from which it resulted that the jury expressed themselves very desirous of obtaining the doctor’s impression.

[I have no doubt the following words led the jury to their decision.]

The medical gentleman said:—

“It is my impression that this death resulted out of a poaching—I will not say affray—but accident. It is thoroughly well-known in these districts, and at such a juncture as the present I need feel no false delicacy, Mr. Petleigh, in making this statement, that young Petleigh was much given to poaching. I believe that he and his companions were out poaching—I myself on two separate occasions, being called out to nightcases, saw the young gentleman under very suspicious circumstances—and that one of the party was armed with the weapon which caused the death, and which may have been carried at the end of such a heavy stick as is frequently used for flinging at rabbits. I suppose that by some frightful accident—we all know how dreadful are the surgical accidents which frequently arise when weapons are in use—the young man was wounded mortally, and so died, after the frightened companion had hurriedly attempted to withdraw the arrow, only to leave the barb sticking in the body and hooked behind a rib, while the force used in the resistance of the bone caused the weapon to part company from the haft. The discovery of the body outside the father’s house can then readily be accounted for. His companions knowing who he was, and dreading their identification with an act which could but result in their own condemnation of character, carried the body to the threshold of his father’s house, and there left it. This,” the doctor concluded, “appears to me the most rational mode I can find of accounting for the circumstances of this remarkable and deplorable case. I apologize to Mr. Petleigh for the slur to which I may have committed myself in referring to the character of that gentleman’s son, the deceased, but my excuse must rest in this fact, that where a crime or catastrophe is so obscure that the criminal, or guilty person, may be in one of many directions, it is but just to narrow the circle of inquiry as much as possible, in order to avoid the resting of suspicion upon the greater number of individuals. If, however, any one can suggest a more lucid explanation of the catastrophe than mine, I shall indeed be glad to admit I was wrong.”

[There can be little question, I repeat, that Dr. Pitcherley’s analysis fitted in very satisfactorily and plausibly with the facts of the case.]

Mr. Mortoun asked Dr. Pitcherley no more questions.

The next witness called was the police-constable of Tram, a stupid, hopeless dolt, as I found to my cost, who was good at a rustic public-house row, but who as a detective was not worth my dog Dart.

It appeared that he gave his flat evidence with a stupidity which called even for the rebuke of the coroner.

All he could say was, that he was called, and that he went, and that he saw whose body it “be’d.” That was “arl” he could say.

Mr. Mortoun took him in hand, but even he could do nothing with the man.

“Had many persons been on the spot where the body was found before he arrived?”

“Noa.”

“How was that?”

“Whoy, ’cos Toom Broown, the gard’ner, coomed t’him at wuncet, and ’cos Toom Broown coomed t’him furst, ’cas he’s cot wur furst coomed too.”

This was so, as I found when I went down to Tram. The gardener, Brown, panic-stricken, after calling to, and obtaining the attention of the housekeeper, had rushed off to the village for that needless help which all panic-stricken people will seek, and the constable’s cottage happening to be the first dwelling he reached the constable obtained the first alarm. Now, had the case been conducted properly, the constable being the first man to get the alarm, would have obtained such evidence as would at once have put the detectives on the right scent.

The first two questions put by the lawyerlike juryman showed that he saw how important the evidence might have been which this witness, Joseph Higgins by name, should have given had he but known his business.

The first question was—

“It had rained, hadn’t it, on the Monday night?”

[That previous to the catastrophe.]

“Ye-es t’had rained,” Higgins replied.

Then followed this important question:

“You were on the spot one of the very first. Did you notice if there were any footsteps about?”

It appears to me very clear that Mr. Mortoun was here following up the theory of the catastrophe offered by the doctor. It would be clear that if several poaching companions had carried the young squire, after death, to the hall-door, that, as rain had fallen during the night, there would inevitably be many boot-marks on the soft ground.

This question put, the witness asked, “Wh-a-at?”

The question was repeated.

“Noa,” he replied; “ah didn’t see noa foot ma-arks.”

“Did you look for any?”

“Noa; ah didn’t look for any.”

“Then you don’t know your business,” said Mr. Mortoun.

And the juryman was right; for I may tell the reader that boot-marks have sent more men to the gallows, as parts of circumstantial evidence, than any other proof whatever; indeed, the evidence of the boot-mark is terrible. A nail fallen out, or two or three put very close together, a broken nail, or all the nails perfect, have, times out of number, identified the boot of the suspected man with the boot-mark near the murdered, and has been the first link of the chain of evidence which has dragged a murderer to the gallows, or a minor felon to the hulks.

Indeed, if I were advising evildoers on the best means of avoiding detection, I would say by all means take a second pair of boots in your pocket, and when you near the scene of your work change those you have on for those you have in your pocket, and do your wickedness in these latter; flee from the scene in these latter, and when you have “made” some distance, why return to your other boots, and carefully hide the tell-tale pair. Then the boots you wear will rather be a proof of your innocence than presumable evidence of your guilt.

Nor let any one be shocked at this public advice to rascals; for I flatter myself I have a counter-mode of foiling such a felonious arrangement as this one of two pairs of boots. And as I have disseminated the mode amongst the police, any attempt to put the suggestions I have offered actually into action, would be attended with greater chances of detection than would be incurred by running the ordinary risk.

To return to the subject in hand.

The constable of Tram, the only human being in the town, Mortoun apart perhaps, who should have known, in the ordinary course of his duty, the value of every footmark near the dead body, had totally neglected a precaution which, had he observed it, must have led to a discovery (and an immediate one), which in consequence of his dullness was never publicly made.

Nothing could be more certain than this, that what is called foot-mark evidence was totally wanting.

The constable taking no observations, not the cutest detective in existence could have obtained any evidence of this character, for the news of the catastrophe spreading, as news only spreads in villages, the rustics tramped up in scores, and so obliterated what footmarks might have existed.

To be brief, Mr. Josh. Higgins could give no evidence worth hearing.

And now the only depositions which remained to be given were those of Dinah Yarton.

She came into court “much reduced,” said the paper from which I gain these particulars, “from the effects of the succession of fits which she had fallen into and struggled out of.”

She was so stupid that every question had to be repeated in half-a-dozen shapes before she could offer a single reply. It took four inquiries to get at her name, three to know where she lived, five to know what she was; while the coroner and the jury, after a score of questions, gave over trying to ascertain whether she knew the nature of an oath. However, as she stated that she was quite sure she would go to a “bad place” if she did not speak the truth, she was declared to be a perfectly competent witness, and I have no doubt she was badgered accordingly.

And as Mr. Mortoun got more particulars out of her than all the rest of the questioners put together, perhaps it will not be amiss, as upon her evidence turned the whole of my actions so far as I was concerned, to give that gentleman’s questions and her answers in full, precisely as they were quoted in the greedy county paper, which doubtless looked upon the whole case as a publishing godsend, the proprietors heartily wishing that the inquest might be adjourned a score of times for further evidence.

“Well now, Dinah,” said Mr. Mortoun, “what time did you go to bed on Monday?”

[The answers were generally got after much hammering in on the part of the inquirist. I will simply return them at once as ultimately given.]

“Ten.”

“Did you go to sleep?”

“Noa—Ise didunt goa to sleep.”

“Why not?”

“Caize Ise couldn’t.”

“But why?”

“Ise wur thinkin’.”

“What of?”

“Arl manner o’ thing’.”

“Tell us one of them?”

[No answer—except symptoms of another fit.]

“Tut—tut! Well, did you go to sleep at last?”

“Ise did.”

“Well, when did you wake?”

“Ise woke when missus ca’d I.”

“What time?”

“Doant know clock.”

“Was it daylight?”

“E-es, it wur day.”

“Did you wake during the night?”

“E-es, wuncet.”

“How did that happen?”

“Doant knaw.”

“Did you hear anything?”

“Noa.”

“Did you think you heard anything?”

“E-es.”

“What?”

“Whoy, it movin’.”

“What was moving?”

“Whoy, the box.”

“Box—tut, tut,” said the lawyer, “answer me properly.”

Now here he raised his voice, and I have no doubt Dinah had to thank the jury man for the return of her fits.

“Do you hear?—Answer me properly.”

“E-es.”

“When you woke up did you hear any noise?”

“Noa.”

“But you thought you heard a noise?”

“E-es, in the—”

“Tut, tut. Never mind the box—where was it?”

“Ter box? In t’ hall!”

“No—no, the noise.”

“In t’ hall, zur!”

“What—the noise was?”

“Noa, zur, ter box.”

“There, my good girl,” says the Tram oracle, “never mind the box, I want you to think of this—did you hear any noise outside the house?”

“Noa.”

“But you said you heard a noise?”

“No, zur, I didunt.”

“Well, but you said you thought you heard a noise?”

“E-es.”

“Well—where?”

“In ter box—”

Here, said the county paper, the lawyer, striking his hand on the table before him, continued—

“Speak of the box once more, my girl, and to prison you go.”

“Prizun!” says the luckless witness.

“Yes, jail and bread and water!”

And thereupon the unhappy witness without any further remarks plunged into a fit, and had to be carried out, battling with that strength which convulsions appear to bring with them, and in the arms of three men, who had quite their work to do to keep her moderately quiet.

“I don’t think, gentlemen,” said the coroner, “that this witness is material. In the first place, it seems doubtful to me whether she is capable of giving evidence; and, in the second, I believe she has little evidence to give—so little that I doubt the policy of adjourning the inquest till her recovery. It appears to me that it would be cruelty to force this poor young woman again into the position she has just endured, unless you are satisfied that she is a material witness. I think she has said enough to show that she is not. It appears certain, from her own statement, that she retired to rest with Mrs. Quinion, and knows nothing more of what occurred till the housekeeper awoke her in the morning, after she herself had received the alarm. I suggest, therefore, that what evidence she could give is included in that already before the jury, and given by the housekeeper.”

The jury coincided in the remarks made by the coroner, Mr. Mortoun, however, adding that he was at a loss to comprehend the girl’s frequent reference to the box. Perhaps Mrs. Quinion could help to elucidate the mystery.

The housekeeper immediately rose.

“Mrs. Quinion,” said Mr. Mortoun, “can you give any explanation as to what the young person meant by referring to a box?”

“No.”

“There are of course boxes at Petleighcote?”

“Beyond all question.”

“Any box in particular?”

“No box in particular.”

“No box which is spoken of as the box?”

“Not any.”

“The girl said it was in the hall. Is there a box in the hall?”

“Yes, several.”

“What are they?”

“There is a clog and boot box, a box on the table in which letters for the post are placed when the family is at home, and from which they are removed every day at four; and also a box fixed to the wall, the use of which I have never been able to discover, and of the removal of which I have several times spoken to Mr. Petleigh.”

“How large is it?”

“About a foot-and-a-half square and three feet deep.”

“Locked?”

“No, the flap is always open.”

“Has the young woman ever betrayed any fear of this box?”

“Never.”

“You have no idea to what box in the hall she referred in her evidence?”

“Not the least idea.”

“Do you consider the young woman weak in her head?”

“She is decidedly not of strong intellect.”

“And you suppose this box idea a mere fancy?”

“Of course.”

“And a recent one?”

“I never heard her refer to a box before.”

“That will do.”

The paper whence I take my evidence describes Mrs. Quinion as a woman of very great self-possession, who gave what she had to say with perfect calmness and slowness of speech.

This being all the evidence, the coroner was about to sum up, when the Constable Higgins remembered that he had forgotten something, and came forward in a great hurry to repair his error.

He had not produced the articles found on the deceased.

These articles were a key and a black crape mask.

The squire being recalled, and the key shown to him, he identified the key as (he believed) one of his “household keys.” It was of no particular value, and it did not matter if it remained in the hands of the police.

The report continued: “The key is now in the custody of the constable.”

With regard to the crape mask the squire could offer no explanation concerning it.

The coroner then proceeded to sum up, and in doing so he paid many well-termed compliments to the doctor for that gentleman’s view of the matter (which I have no doubt threw off all interest in the matter on the part of the public, and slackened the watchfulness of the detective force, many of whom, though very clever, are equally simple, and accept a plain and straight-forward statement with extreme willingness)—and urged that the discovery of the black crape mask appeared to be very much like corroborative proof of the doctor’s suggestion. “The young man,” said the coroner, “would, if poaching, be exceedingly desirous of hiding his face, considering his position in the county, and then the finding of this black crape mask upon the body would, if the poaching explanation were accepted, be a very natural discovery. But—”

And then the coroner proceeded to explain to the jury that they had to decide not upon suppositions but facts. They might all be convinced that Dr. Pitcherley’s explanation was the true one, but in law it could not be accepted. Their verdict must be in accordance with facts, and the simple facts of the case were these:—A man was found dead, and the causes of his death were such that it was impossible to believe that the deceased had been guilty of suicide. They would therefore under the circumstances feel it was their duty to return an open verdict of murder.

The jury did not retire, but at the expiration of a consultation of three minutes, in which (I learnt) the foreman, Mr. Mortoun, had all the talking to himself, the jury gave in a verdict of wilful murder against some person or persons unknown.

Thus ended the inquest.

And I have little hesitation in saying it was one of the weakest inquiries of that kind which had ever taken place. It was characterized by no order, no comprehension, no common sense.

The facts of the case made some little stir, but the plausible explanations offered by the doctor, and the several coinciding circumstances, deprived the affair of much of its interest, both to the public and the detective force; to the former, because they had little room for ordinary conjecture; to the latter, because I need not say the general, the chief motive power in the detective is gain, and here the probabilities of profit were almost annihilated by the possibility that a true explanation of the facts of this affair had been offered, while it was such as promised little hope of substantial reward.