Amazon - Website

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

The Spotted Panther:

James Francis Dwyer:

eBook No.: 2200011h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: Jan 2022

Most recent update: Jan 2022

This eBook was produced by Colin Choat and Roy Glashan

by

James Francis Dwyer

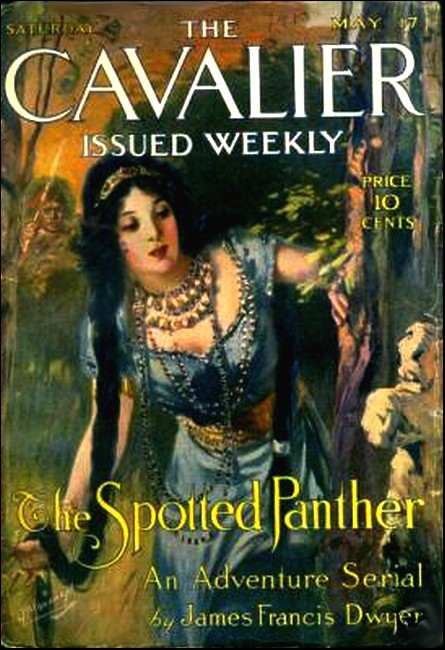

The Cavalier, 17 May 1912, with first part of "The Spotted Panther"

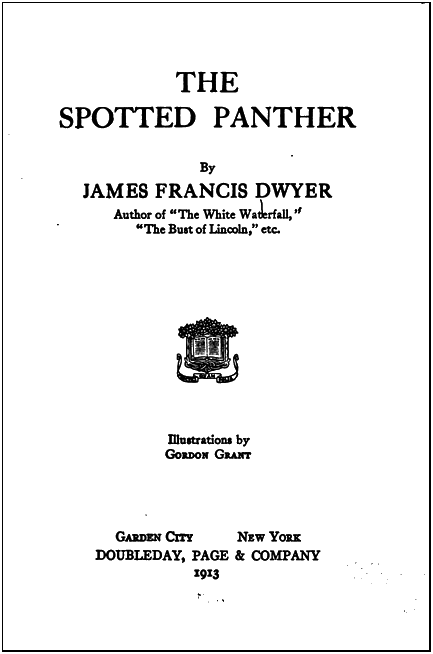

"The Spotted Panther," Doubleday, Page & Co., Garden City, NY, 1913

James Francis Dwyer

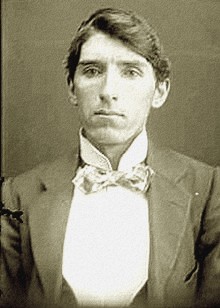

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

Title Page of "The Spotted Panther"

Doubleday, Page & Co., Garden City, NY, 1913

Title Page of "The Spotted Panther"

W.R. Caldwell, New York, 1913

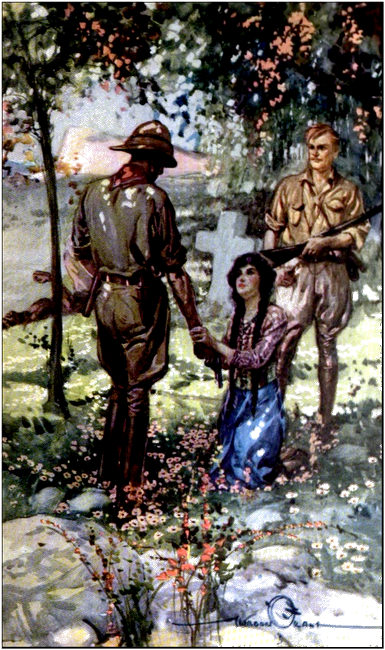

Frontispiece.

Nao moved out upon a huge platform of rock

and

we watched the Dyak wave the torch above his head.

The House Of The Dream Smoke

TO the man who thinks that the United States of America is the milk

and honey section of the world, and that New York is the centre of

that section, there is no news that could be more distressing than

the knowledge that he is as far away from that centre as he can

possibly get. Chico Morgan made this discovery on the summer

evening that he worked out the geographical position of

Banjermassin. Broadway was as far to the east as it was to the

west, and Chico cursed softly as the home-longing produced by the

discovery bit into his soul.

"Just think," he growled, "we've got the soles of our shoes directly opposite the soles of the shoes worn by the fellows who are tramping up and down the White Way, and what is more, we haven't got the money to get one step nearer home."

Chico's statement was the plain truth. New York was on the opposite side of the world, and we were financially incapable of lessening the intervening distance by a single league. Up before our mental eyes came pictures of miles of electric-lighted streets with whining trolley cars and goblin-eyed automobiles, and Morgan thoughtfully doused the slush lamp lest one of us might notice the suspicious moisture in the eyes of the other. There is no hunger like the home-hunger.

After a long silence, Chico spoke. "Let's take a walk around," he said. "This room is like a furnace."

We stumbled down the rickety stairs and out into the narrow street that appeared to be crammed full of the real extract of gloom. The occasional lamp that blinked fearfully at a corner seemed to fight for existence against the encompassing darkness, and the houses were blotted out with the thick blanket of the tropical night. Upon the little puffs of air that came prowling up the Banjer from the Java Sea were all the odours of the East. Smells of spices, of wet earth, bean-oil, marigolds, incense, and burning punk came to our nostrils, and we longed with the longing of the exile for the clean sweet smells of the home country that was so far away.

There is a curious sense of expectancy in a tropic night. The earth seems to be in a state of fever, and one waits for a change with the anxiety of a nurse at the bedside of a patient. And that peculiar feeling went with Chico Morgan and me on that night through the streets of the old Dutch town of Banjermassin. The dark, crooked streets were the abodes of mystery, and the whispers that came from stoops and passageways where a mixed population gasped in various stages of deshabill?, stirred us strangely as we walked along.

"When I get back," stammered Chico, addressing a row of tamarind trees that lined the street, "I'll never stray farther than Fort George or Coney! Honest! I won't! These leagues of space that lie between us and the Battery make me feel as if I had been sandbagged every time I think of them."

"You'll stay about three weeks," I suggested. "Three weeks or less."

"I'll stay the rest of my life!" he roared indignantly. "I'll never——"

We stopped and pushed our heads forward. From a little dark alley came the faint sounds of a phonograph, and we listened eagerly. The instrument was sending into the spice-scented air of Banjermassin a tune that set our blood tingling.

"Great Scott!" growled Chico. "Do you hear that?"

"Of course I hear it!" I answered. "Some Dutchman has got a bunch of American records, and he's entertaining his friends with the 'Star Spangled Banner.'"

"We'll call on him," said Morgan. "It's possible—barely possible—that we might find a millionaire from Newport who has a yacht tied up somewhere in the harbour."

Chico turned into the dark alleyway, and I followed without protest. The search for the phonograph and its owner would take our thoughts for the time being from the contemplation of the films of home scenes which memory unwound, and that was something to be thankful for. Besides, it was barely possible that we would find a countryman, not a millionaire, as Morgan suggested, but some recruit of the American legion of devil-may-care that sits upon the rim of the earth and whose members look toward God's Country with the same reverence that the good Mahommedan looks toward the Kaaba of Mecca.

The phonograph had stopped playing before we had taken ten paces down the alley, but through the shutters of a shack, at the extreme end of the passage, rays of light shot out into the night like the white spears of crusaders, and Chico Morgan and I silently approached the apertures through which the light was streaming. The East breeds curiosity, and we had no compunction about playing the part of Peeping Toms in our endeavour to find out who owned the phonograph whose squeaky voice annihilated space.

The room into which we looked was an opium den of the lowest kind. Chinese, Dyaks, Javanese, and filthy Hindus sprawled upon the plaited fibre mats that were spread upon the floor, while immediately beneath our peepholes, and so close that we could have touched him with our hands if the spyholes had been large enough to insert our arms, lay a white man.

There was no mistake about his colour. The attendant Mongolian had just prepared his "pill," and the light from the little brass lamp fell full upon his face. It was fearfully emaciated, the skin hanging loosely upon the bones, while the long, lean hands that clutched at the pipe appeared to be semi-transparent as he waved them between us and the flickering flame.

For a full minute we had an undisturbed view of the place. The small cheap phonograph stood on a raised dais at the far end of the room, and upon this dais sat the Mongolian proprietor of the outfit. The smokers were silent, except for the occasional muttering of a drugged dreamer, but while we peeped through the chinks in the matchwood and attap walls, the dead silence of the place was shattered in a startling manner. A wild roar came from a curtained opening at the rear of the dais, and next instant the curtain was torn aside, and a whirling mass of fighting men was flung into the big room. For a moment we could see nothing but flying legs and arms, then our startled eyes gripped the meaning of the tornado. A red-headed white man of tremendous proportions, possessing the limbs of a Greek god and the fighting face of a Viking, was battling his way up the room, and hanging to him like wolves to a buffalo were a dozen screaming Chinamen and Malays!

Chico Morgan smothered an exclamation and pressed his face close to the observation hole. A fight always interested Chico, and it was a battle royal that we were looking at just then. That redheaded man tossed the brown and yellow vermin hi all directions as he fought his way toward the mat where the emaciated white man fumbled with his opium pipe. My! wasn't he a fighter! That place was a warren that belched forth assailants at the command of the fat Mongolian upon the dais, but Redhead towered above them like a battleship above a swarm of pirate junks. I thrilled as I watched him. He was a mighty man. The arms he swung were such as Ajax might have envied, and each time one of his tremendous fists crashed against the head of a nigger, there was one assailant less in that place of smells and deviltry. Right and left those screaming natives got the sledgehammer blows, and the giant with the red head roared defiance at them. He was a glorious fighter.

"Jumping jigsaws!" I cried. "Did you ever see such a man?"

Chico Morgan did not reply to my question, and when I turned to search for him he was gone. I jumped back to the spyhole and looked. Chico had forgotten Broadway. He had his big back to the back of Redhead, and they were fighting like the Seven Devils that guard the one door of escape that leads from the Malayan hell!

I am treasuring within my mind the memory pictures of that battle so that I may warm my blood with them in the winter of my old age. It was a fight that Homer would have put into jewelled phrases. There were never two gladiators like Chico Morgan and Redhead, and they swept up that room like a tornado, sending Malays, Chinese, and greasy Hindus sprawling backward from their punches.

The white man on the bench immediately beneath my spyhole stared at the battle with opium-dulled eyes. Although he was only a few feet from the hole through which I watched the fight, the screams of the natives prevented him from hearing the insane yells of encouragement I shouted through the aperture. I must confess that I had no desire to join in the fray at that moment, and I am unable to give a reason. The manner in which those two were disposing of their foes fascinated me to such an extent that I could not move from the spot where I was standing.

The pair of giants reached the white opium-smoker, the mob still attacking, but now somewhat wary of the four fists that smote like the hammer of Thor whenever a body came within hitting distance. The fat Mongolian proprietor was shrieking protestations against the invasion and endeavouring to urge his henchmen to the attack, but the half-naked retainers were none too anxious to clinch with the fighting pair.

"Come on!" roared Chico. "Come on, you yellow scum! I'd fight a million of you!"

Redhead glanced at Morgan, smiled like a big boy, then stooping swiftly, he put his arms around the emaciated white man with the opium pipe, and with a laughing cry to Chico he turned to fight his way back to the door.

I came to life at that moment. Racing round the shack, I dashed through the door and down the long room, shrieking to Redhead as I ran. He understood at once that I was a friend. Very tenderly he passed me the thin form of the opium smoker, and then with Chico upon one side and Redhead upon the other we dashed for the door.

"Pound them!" roared Morgan.

"Straight punches!" shouted Redhead. "We've got them scared!"

Now as I write this narrative I am wondering which of those two, Chico or Redhead, was the greatest fighter, and as I look back upon that fight in the opium den, and the other fights when they battled against greater odds than they faced at their first meeting, I am in doubt as to which was the better man. I know well that Chico Morgan would never admit defeat, but when I tell of the prowess of the red-headed man we met that evening at Banjermassin, the person who reads this narrative will understand that the two were the kind of men who would have led their tribes to battle in the days when the world was young. When we forget how to fight we will be on our way back to the jellyfish state that we emerged from five million years ago. Aggressiveness is life itself. The men who are fearless are big men, and the good Lord never made two bigger men than the two who battled back to back in the filthy opium den by the banks of the Banjer.

As we neared the door a naked Kling sprang forward, a short knife lifted high in his muscular hand. His evident intention was to drive the broad blade into the thin white man we were endeavouring to take from the place, but Chico Morgan thwarted the intention. The Kling received Chico's big fist upon the jaw, and he was lifted clean off his feet and hurled against the matchboard walls with a force that shook the shack. Redhead unloosed a grim chuckle, but as he laughed, the fat proprietor of the place hurled a small teakwood table at the hanging lamp, and the wild m?l?e was blotted out by the darkness.

It was at that critical moment that the opium smoker came out of his stupor. "This way, Lord Edwin!" he shouted, as he wriggled out of my arms. "This way!"

The thin one knew that place like a blind man knows his bedroom. Clinging to my arm and shrieking to Redhead, he reached the door while the mob rolled over us like a wave. I wrenched the Dutch lock from the thin boards, and with a head ringing from a blow with a mallet, I tumbled out into the cool night air.

"Chico!" I yelled. "Here, boy! This way!"

Morgan came through the opening with a rush that sent me sprawling, then the red-headed man battled through like a big hippopotamus, kicking viciously at a sinewy Chinaman who clung to his right leg. Round the shack to the alley we raced together, Redhead and I supporting the smoker, while Chico discouraged the advance guard of the foe.

"Can you run, Phillip?" asked the big man, stooping over the rescued one.

"Run, Lord Edwin?" gasped the other. "No, I can't run! My running days are over. Clear out and leave me! You'll get into trouble for this business!"

Redhead ignored the advice by seizing the smoker around the waist, swinging him to his shoulder as if he were a child, and, with Chico and me at his heels, dashing into the soft night. A thousand odours floated upon the heavy air. Punk and incense, flower, perfumes and the sour odours of mudbanks made strata through which we rushed madly, Redhead running with no apparent effort and paying no attention to the gurgled protests of the man upon his shoulders.

We zigzagged through narrow passages, splashed through wet places where the water from the river had swamped the track, and wriggled knee-deep in mud through a mire that threatened to engulf us. Once we stopped for an instant and listened intently. From behind came the faint plap-plap of pursuing feet, and the big man cursed softly as he made a movement to lower his burden. Chico understood that movement. He slipped back into the darkness, and after a short interval there came to our ears a yelp of pain, the quickened patter of bare feet in hot retreat, then Morgan's returning footsteps.

"All right," he muttered. "It was only a Chinaman. Here, let me lend you a hand to carry your friend."

"No, no," said Redhead. "He's no weight at all. He's light."

"Light?" chuckled the smoker. "Of course I'm light! Hee, hee! I'm all smoke! All smoke!"

Redhead muttered something beneath his breath, and we ran on. On and on we went, through the waiting night, through the dark passageways, and as we ran we forgot Broadway with its whining trolley cars and goblin-eyed autos of which we had been dreaming an hour before.

The Wonder Chalice

IT was the opium smoker who called a halt. Slipping from the

shoulder of Redhead, he opened a wooden door in a wall that was

'thickly covered with wistaria and Bougainvillea, and we followed

him into the inclosure.

"This way," he murmured. "Keep close to me." With Redhead supporting him, he stumbled along narrow pathways bordered with tropical flowers whose sweet odours half intoxicated us. It was a place that naiads and dryads might choose for a romping ground, and the silvery tinkle of fountains came to our ears with the drowsy murmur of wood doves that our steps disturbed.

"Steady," muttered the opium smoker. "There are steps here."

Chico Morgan and I followed up the half dozen steps, and found ourselves upon the piazza of a bungalow that was completely hidden by the luxuriant tropical growth. And at that moment, just as we considered the adventure at an end as far as we were concerned, the red-headed man thought it an opportune time to introduce himself.

"My name is Edwin Templeton," he said quietly. "I'm——"

"Lord Edwin Templeton," corrected the opium smoker, as he fumbled with a key. "Lord Edwin Templeton, I say!"

"There are no titles where you and I are concerned," said the big man, gripping Chico's hand. "You fight too well for any fool prefixes to be between us. I'm plain Templeton, or Red, if you like a shorter word."

Chico Morgan laughed the easy, unabashed laugh of the carefree man as he returned the grip. "I'm glad there's no title," he said quietly. "We're not in the habit of using them much out our way. My name is Chico Morgan, and this is my mate, Jack Lenford."

"Americans?" asked Templeton.

"Sure," answered Chico; then, as if the question brought back the attack of homesickness, he added: "And mighty sorry that we're so far away from the home country."

The opium smoker, still protesting against the omission of Templeton's title, had managed to unlock the door, and Redhead motioned us to enter the wide hall of the bungalow. But Chico Morgan demurred. The fight being over, and all danger of pursuit out of the question, he had no further interest in the proceedings, and he attempted to excuse himself.

But the Englishman had no thought of letting Morgan escape so easily. He gripped Chico's arm as we attempted to back away, and his heavy voice boomed through the night.

"Do you think I could have fought my way out of that place without your help?" he cried. "Here! stop! Have you got any engagements?"

"None," answered Chico. "We came down from Singapore in The Light of Asia, jumped her here because he had a difference with the mate, and now we're watching the horizon to grab the first opportunity that will bring us within range of Sandy Hook."

Templeton gave a gurgle of joy, and his grip tightened. "I can put you next to the opportunity," he cried. "Come inside. I want a man or two, and by the Toe of Buddha! you're going to fill one of the jobs."

He half dragged Chico into the hall of the bungalow, and I followed. The place was lighted by a hanging lamp of hammered silver, and the soft light fell upon Chinese embroideries that covered the walls. Ebony settees curiously inlaid with mother-of-pearl stood upon each side, while the curtain that separated the hall from the room which the opium smoker had entered bore a representation of Buddha sitting beneath a bo-tree, the whole piece outlined with Burmese spinels that sparkled in the lamplight.

The protesting high-pitched voice of the opium smoker came from the room as Templeton reached the curtain, and then our ears caught the sound of a woman's voice pleading with him like a mother pleads with her child. The Englishman entered the room with Chico and me at his heels, the look upon Morgan's face proving to me, if not to Templeton, that he had an inclination to bolt from the premises. Upon a couch at one side of the room was the opium smoker, and sitting beside him was a girl of wonderful beauty, whose white, shapely hand stroked the worn face of the debauchee at her side. Although the haggard face of the man was different from hers as one face could possibly be from another, yet the brows of the two, and the whimsical expression of the mouth, peculiar to both, proclaimed a relationship.

The girl rose quickly as Chico and I entered the room, and Templeton introduced us.

"These are two good Americans who helped me a little to-night, Evelyn," he explained. "Mr. Morgan and Mr. Lenford, this is our friend's sister, Miss Courtney."

"And I'm Phillip Courtney," mumbled the man on the couch. "I always introduce myself. By George!" he cried, turning to Chico, "you're the greatest fighter, excepting Lord Edwin, that I ever saw! Absolutely the best!"

The girl touched a bell, and a Chinaman answered the summons. She instructed him to bring refreshments, and then excusing herself on account of the lateness of the hour, she left the room, leaving the four of us together. It was then that Chico and I had our first good look at Red Templeton. He sat under a lamp in the centre of the room, and the light fell full upon his remarkable face. It was an extraordinary face. The eyes were clear blue, full of a boyish innocence and brimming over with life and laughter, but the nose, jaw, and brow gave a strength and fighting quality to the face that told the observer that the laughter in the blue eyes was likely to disappear at any moment that the fighting devil beneath the surface announced that it was not the proper time for merriment. To me he appeared a superman on that evening, and the impression has never altered. A man too big for the petty conventions of the life he had been born to, he had thrown that life aside and had wooed adventure where Romance flies her flag of gold on the rim of the earth. His was the true patent of nobility. He could earn his right to lead his people by the tremendous strength in the big arms and the hallmark of courage that one observed upon his face.

For about thirty minutes he plied Chico with questions concerning our wanderings, and while we conversed, the half stupefied Courtney lay upon the couch and muttered incoherently, interrupting occasionally with a question or remark that was totally irrelevant to the matter we were discussing.

"And you are open to an engagement?" asked Templeton, after Chico had finished a recital of our wanderings.

"I guess we are," answered Morgan. "This burg has little attraction for us."

Templeton surveyed Chico for a full minute, a half smile showing about his handsome mouth, then he stood up, walked toward a cabinet at the end of the room, unlocked it, took something from within, and started back to us. It is strange that every movement he made in approaching that cabinet and returning to his place beneath the lamp is etched upon my mind by the tremendous happening that immediately followed. The mind at moments of extraordinary stress is peculiarly sensitive to impressions, and I recall now how Templeton circled outside the light of a silver sconce as he came back to us. He wished to produce the utmost effect, and he was successful. Arriving at his seat, that was immediately beneath the lamp, he flung back the flap of his coat that was concealing the object that he carried, and we saw!

Now on a summer night when the smell of wet earth or crushed flowers brings back to my mind that night in Banjermassin, I dream for hours of the glory that we saw. I shall dream of it till I die. Perhaps, like the Burman who asked that he might dream of the Shwe Dagon Pagoda after he reached the paradise of the faithful, I might dream of that for all eternity.

Chico and I thrust our heads forward when the big Englishman drew back his coat, and we gave a joint cry of wonder that roused Courtney from his stupor. Templeton's hands seemed to be holding a chalice that sent out white spears of light into the corners of the room, and we choked as we looked. There was never anything made like that. Never! It was the most glorious thing that has ever been created by the hand of man, and, while the world is a world, nothing will be made that will equal that.

Chico Morgan broke the little silence that followed the gurgle of wonder we emitted when we caught the first glimpse of the thing. Chico stood up, made a movement toward Templeton, paused, and then stood with both hands extended.

"The Chalice!" he cried. "The Chalice of Everlasting Fire!"

Red Templeton laughed softly as he watched Morgan's face. The Englishman was pleased at the look of amazement that was upon Chico's sun-tanned countenance.

"You've guessed it," he said quietly. "It is the Chalice of Everlasting Fire!"

Body o' me! we had a curious feeling just then. It seemed as if we had waited all our lives to get a glimpse of that thing in the Englishman's hands. It was extraordinary what effect it had upon us. We seemed to drink the glory and the beauty of it through our eyes—drink it in to satisfy a longing that had asserted itself suddenly. It seemed as if our souls had been waiting for a glimpse of that wonder chalice, and that we had been in ignorance of that longing till the thing had been thrust suddenly before us. I suppose it was the stories of the vessel that had created the subconscious appetite. In the peculiar atmosphere of the Orient that chalice had lived upon the spice-scented breezes for centuries. Lived, mind you! In the fo'c'stle of every blistered tramp that hooted off nipa-palm villages in search of cargo, the Chalice of Everlasting Fire was the subject of discussion. Men talked of it on the stinking Wusung, whispered of it at the pearl fisheries at Thursday Island, and dreamed of it as they looked upon the snows above Darjeeling. It had a dozen names. Dyak, Kling, Chinese, Jap, Tamil, Hindu, Shan, Khond, and Rajput knew it by a name of his own. It was the Vessel of Flame, the Holy Cup, the Burning Pitcher, the Goblet of Life, and a dozen other names, but English and American sailors and rovers spoke of it as the Chalice of Everlasting Fire. Somewhere in his notes on the Malay Archipelago, Markham has alluded to the legend as an Oriental counterpart of the story of the Holy Grail, and when we saw it that night in Banjermassin, we had no need to wonder how it had led its seekers to think of it as the miraculous cup of holy legend.

It was a high chalice of dull red gold, the gold that one sees in old coins of the East, and circling around it from the stem to the rim was a snake made of diamonds of extraordinary brilliancy and purity. That snake was alive! As we looked at it, the light reflected from one stone to another, seemed to run along the serpent like a tremor of sparkling fire, while the glorious stone set on the rim exchanged stabs of light with its counterpart set in the very bottom of the cup. Mother o' me! it was well named! As we looked at it we knew why it had been woven into the chanties of the blunt-nosed tramps, the songs of the Malay pirates, and the nasal war hymns of the Dyaks. We wondered stupidly how any one could keep the whereabouts of the marvellous thing a secret.

It was Courtney, the opium fiend, who roused us from the torpor which the sight of the chalice had brought upon us. The half-crazy smoker lifted himself upon one elbow, glanced at the shining cup, then burst into a fit of hysterical laughter that echoed through the bungalow.

"Put it away, Lord Edwin!" he screamed. "Put it away! Take it out of my sight! It's mine, confound you! Don't leave it there or it will drive me crazy!"

Templeton pulled a screen between the couch and the table upon which the chalice rested, and Courtney became silent. Red sat down again and watched Chico. The white fire that seemed to be streaming continuously up the body of the snake prevented us from moving our eyes from the thing.

Presently Red leaned forward and put a question. "You know the story of it?" he asked.

Chico wet his lips, made an attempt to speak, failed, wet his lips again, and then whispered an answer.

"A part of it," he breathed. It was peculiar how that vessel made one cautious about raising one's voice. I suppose all truly magnificent sights, such as a marvellous dawn, a wonderful sunset, a snow-capped mountain or a tremendous chasm have a quieting effect upon the beholder, and that chalice had the same effect upon us. We wished to observe it in complete silence, and Courtney's hysterical laughter had jarred us exceedingly.

Templeton pulled his chair closer and spoke to us in a low voice. "Do you know when it slipped out of the sight of white men?" he asked. "I mean the last time it was lost to the outside world."

"Over a hundred years ago, perhaps," answered Chico. "Is it more?"

Templeton laughed softly and stepped across to the teakwood table. Very tenderly he turned the chalice upside down and pointed to an inscription upon the bottom. The letters were graved roughly, but they were quite distinct, yet the words were unintelligible to us.

"It is Portuguese," said Templeton. "Shall I translate?"

Chico nodded his head, and Red translated. The inscription ran:

TO MY KING, JOAM II, FROM

ENRIQUE DE GAMA, WHO IS

DYING IN THE SEA OF CHINA.

"And who was King Joam II?" asked Morgan.

"The king of Portugal at the end of the fifteenth century," replied Red. "He was on the throne when the Portuguese started to send their old galleons around the world, and our friend, Enrique de Gama, wanted to send this little present to him when he was dying."

"And it never got there?"

"No; and it is the reason why it didn't get there that interests us at the present. After Enrique de Gama died, his sailors ran the ship ashore somewhere between here and the straits of Pulo Laut, and do you know what happened to those gentle mutineers?"

"The Lord only knows," murmured Chico.

"They were taken prisoners by the Kyans, the Orang Bukkit tribes, and the loot and the sailors were carried up into the hills."

"And—and," stammered Morgan, "who brought the chalice back here?"

Templeton pointed to the wreck upon the couch.

"He did," he answered. "At least he was one of the two that brought it back."

"And the other?"

"Is a Hindu. Courtney remembers very little of what happened to him from the time he got lost at the headwaters of the Barito but Gung knows. I'll call him."

Templeton touched a gong, spoke to a Dyak servant who entered, and then flung a cloth over the chalice.

"Gung cannot look at it," he explained. "He knows its history. Enrique de Gama gathered the loot from a Buddhist temple in Kelantan, and only a holy man can look at this thing. Here he is."

A Hindu, tall and muscular looking, with a long scar extending obliquely from the bridge of the nose to the left jaw, entered the room with noiseless feet. His beady eyes wandered over the apartment, passed over Chico Morgan and myself, then, as if he sensed the chalice, he fixed his gaze upon the cloth which Templeton had thrown over it, bowed three times, and started to chant softly in Hindustanee.

Red put up his hand to silence him but Gung could not be silenced till he had made his invocation. When that was concluded he was the servant again and he stood erect waiting for orders.

"Gung," said Templeton, moving closer to the Hindu, "I want you to tell again the story of what happened to you and Sahib Courtney. Tell it as you like. Sit down here and take your own time."

The Hindu pushed his chair as far from the teakwood table as he possibly could, then with another bow to the thing beneath the cloth, he started to speak.

I cannot write that story here. No one could write it and be believed. It was marvellous, extraordinary, unbelievable. And yet, although our so-called common sense tried to rise up and throw back the statements that poured into our ears, our souls knew that the Hindu was telling the truth. Yes! The story was beyond the possibilities of imagination. No brain could build it up. It had the props of fact beneath it, and we listened with open mouths and throbbing hearts. The narrative dripped truth, and when the Hindu chanted away in the stillness of that room with the little puffs of wind carrying the old, old scents of the Orient to our nostrils, we seemed to see everything that he spoke of. What a story it was! Now and then as we tried to shake ourselves free of the peculiar spell which the Hindu's words put upon us, the story seemed to rise up and overwhelm us with its novelty and force. And the Hindu is the greatest story-teller in the world. He creates a shadow effect about his paragraphs and it is in the portions of his narrative that he only half tells that the imagination can dive and drag out wonderful thrills. That night in the bungalow in the Garden of Dreams we heard for the first time of the Spotted Panther, of the White Mias, of the Parang of Buddha, and a thousand other matters that made the skin upon our necks prickle as Gung unfolded his tale. It was a terrible story.

The Hindu finished as the gray dawn crept into the room, and after a long silence, Chico nodded to the object that was underneath the cloth. "And that is not to be compared with the Great Parang," he said quietly.

Gung made a peculiar noise with his mouth, and rolled his eyes in terror. "There is nothing in the world like the Great Sword," he murmured.

"There is not," said Templeton.

Courtney woke at that moment, and he stared at us with stupid, unseeing eyes. Suddenly he stood up and made a rush at the Chalice of Everlasting Fire, and Gung, horrified at the thought of the wonderful cup being uncovered in his presence, slipped from the room with the speed of a rock snake.

Red Templeton took no notice of Courtney as the latter caught up the chalice and hugged it to his bosom. Templeton was looking at Chico, and Morgan read the longing behind the blue eyes as he returned the glance.

"You are going up?" he asked.

Templeton nodded. "I'm all ready to go," he answered. "But I wanted a mate, a fighting mate, and by the beard of Mahomet, you're the man I want!"

He stood up and put out his hand, and Chico took it. They were two big men, American and Englishman, and they had summed up each other's worth. With the insane Courtney hugging the Chalice of Everlasting Fire, they stood face to face and their grip tightened.

Chico Morgan glanced at the chalice and sighed softly. The first beams of the morning sun had found their way through the window, and the snake made out of the flashing diamonds seemed to thrill with life as the bright rays fell upon him. We felt sure that it was alive. Gung had told us that it represented the Serpent of Death that drank continuously from the Chalice of Life, and it awed us at that moment. And Red Templeton and the Hindu had asserted that the value of the Great Parang of Buddha was a million times greater than the value of the Vessel of Flame. And we knew that they spoke the truth.

"I'll go," said Chico. "The sooner we start the better."

The White Mias

WITH a desire to save the reader from anything that might seem of

little interest, I am omitting a detailed account of the nineteen

days that elapsed between that night of the fight in the opium den

at Banjermassin and the afternoon of the day we arrived at the

Place of Evil Winds. They were nineteen days of hard travel, but

there were few happenings in the time that were worth recording. We

had travelled up the Barito to its headwaters, crossed the

"lallang," or high grass plains, and had entered the jungle

fastnesses of the Tawah Mountains. Gung was our only guide and

authority. As far as we knew, Courtney, the opium fiend, and the

mutineers from the ship of Enrique de Gama were the only white

people who had ever travelled over that region. The interior of

Borneo is unexplored country, more inaccessible than the darkest

portions of Africa, and ten times more uncanny to the person who

braves its silent jungles and weird plains. Crossing the

grass-covered stretches our ankles were festooned with leeches, and

the pests became more troublesome as we advanced. The ten Dyaks and

Gung rubbed their ankles at intervals with the juice of the betel

nut, and Red Templeton, Chico, and I followed their example.

The Place of Evil Winds was well named. Whether Gung's imagination was responsible for the name, or whether, as he persisted, a man of the Orang Bukkit tribe had translated the meaning of the Kyan word when he visited the place with Courtney, we could not tell, but there was no name that could be more appropriate. It was a section of gray desert, wedged in between walls of surrounding jungle, and that spectral patch of sand was dotted with round boulders that the Dyak carriers looked at with aversion. The care which they exercised in keeping clear of the stones in crossing the strip of desert provoked Temple-ton's curiosity, and he asked a question.

"Why are they dodging the rocks?" he asked.

Gung, the fountain of wisdom, unbosomed himself. "They are afraid," he murmured. "The fact of the rocks being here explains why the breeze does not blow upon this place."

He pointed to the waving tops of the green walls of tapang, mohor, and sandalwood trees that hemmed us in on all sides, then he wet his finger and held it up.

"There is no breeze here," he said quietly. "The trees are bowing to the south wind, but it does not blow in this place."

Templeton laughed. "We're sheltered by the trees," he explained; "They act as a barrier, that is why."

Gung's white teeth glistened in a smile that expressed his incredulity. "We think it is these," he said, pointing to the round boulders. "The wind will not blow upon them. They are the ten thousand sons of Prang, and they slew their father. That is why they were turned into stone out here in the waste where the breezes turn aside lest they will wake them."

Templeton looked at Chico, and Chico grinned. "Better leave them alone," he said. "Their beliefs are in their blood, and all our talking wouldn't change them a bit."

I remember that we sat conversing late that evening. Within our brains the story that Gung had told to us that night in Banjermassin was rioting madly. That Chalice of Everlasting Fire was always before our minds, and a score of times upon the journey we had questioned the Hindu concerning the great sword with the emerald handle that was called the Parang of Buddha. There were a thousand legends told concerning that sword. We had spoken of them in the hot, still nights, and we prayed that Gung's bump of location would take him back to the place where Courtney and he had purloined the chalice from the cave that was close to the kampong of the Spotted Panther. It wasn't a treasure hunt that we had set out upon. We were searching for something that was beyond price. The Great Parang had been plaited into the history of the Orient so that it possessed a value that was ten thousand times greater than the mere value of the gold and precious stones of which it was composed.

"You cannot put a value upon it," said Chico, on that evening we camped at the Place of Evil Winds.

"Value?" cried Templeton, as he crawled under his blanket. "If it were possible—if it were possible, I say, to bring the Great Parang of Buddha to Benares and lay it in the Mosque of Arungzebee, there would be a revolution in India inside of seven days! Inside of seven days, mind you! The news would have travelled in that time from Calicut to Chitral, and from Quetta to Mandalay. Great Scott, man! We could stir three hundred million human beings in a way that would make them push the British into the Bay of Bengal. And the British are my people! I'm a Britisher, but I must go in search of this thing if it wrecks a dozen empires. I'm going to get some sleep. We've got a big march in front of us to-morrow."

I went to sleep and dreamed a dream in which I thought that Chico Morgan and Red Templeton carried the Parang of Buddha to Benares, but the British Government, hearing of the discovery, bribed them to secrecy by making them princes of the Punjaub and Rajputana, Sind, and Nepal.

Chico broke the dream by prodding me gently with the toe of his boot, and with a feeling that something had gone wrong I sprang to my feet. A moon, white and scared-looking, swung above the wall of sandalwood and ebony trees, and everything was washed with a pale light that made it possible to see across the stretch of open desert upon which we had pitched our camp.

Red Templeton and Morgan were standing side by side, their eyes fixed upon the ten Dyaks and the Hindu, who were kneeling in a little cluster upon the sand.

"What's the matter?" I stammered. "What is wrong?"

Templeton's right hand was upon his revolver as he turned toward me, while Chico held a Winchester ready.

"Do you remember Gung's story about the White Mias?" asked Red.

"Yes," I answered. "What about it?"

"Well, these infernal lunatics have got a notion that she is near. We don't know whether Gung has been filling their heads with nonsense, or whether the sight of some big orang-utan has unsettled their nerves, but they're half crazy with fear."

It is strange how the mind stores a remark as if awaiting a suitable opportunity of calling your attention to the wisdom stored within it, and which you probably failed to see when you first heard it. My mind played a trick of that kind upon me at that moment. It recalled the remark of Hooper, an American trader at Singapore, a man who had seen more than any other ten men in the Orient. "Belief," said Hooper, "is only a matter of stage setting. If you have the right atmosphere for a story the hearer can believe anything."

Now on that night at Banjermassin when Gung told of the big White Mias who came down out of the mountains with the orang-utan legion to harry the Trings, the Orang Bukkit, Punans, and other sub-tribes of the Kyans, we didn't pay much attention. The story of the Chalice of Everlasting Fire and the treasure which Courtney and the Hindu left behind them in the hills made the tale of the queen of the orang-utans a minor matter, but when I stood with Templeton and Chico watching those half score Dyaks and the shivering Gung, that story took on a complexion that was totally different. The fear which gripped the eleven seemed to come out to us. Templeton and Chico, two men who had faced ten thousand dangers, watched the surrounding jungle with keen eyes, and Red cursed softly under his breath. The tops of the trees were still waving slightly as if nodding to us, and we thought of Gung's story about the wind as we looked at all points of the compass.

"That infernal Hindu has told them tales till he has put their nerves on edge," growled Templeton. "Get them up, Morgan! They'll work themselves into a state of hysteria if we leave them there much longer."

Chico and I were just longing for something to do at that moment, and we started in with a will to break up the cluster. But the danger which the eleven sensed upon the air bound them tighter than iron bands. A few hours before they had been quarrelling with each other, but now when Chico and I attempted to stop their infernal whimpering by dragging them apart, the enemies flung their arms around each other, so that when we tried to lift one to his feet, we were handicapped by the weight of the other ten trying to keep him upon his knees. It made Chico as vicious as a bobtailed viper.

"Get up!" he yelled. "You infernal idiots! No Mias! No! It's a fool yarn!" "Mias, tuan!" they groaned. "Devil Mias!"

Chico got Gung by the shoulders, and by sheer brute strength lifted him to his feet. "Tell them that-yarn is a lie!" he roared. "Tell them, you old fakir! Quick!"

"It's true, sahib!" gasped the choking Hindu. "It's all true!"

Morgan shook him till his teeth rattled, but Gung wouldn't contradict the yarn that he had circulated, and when Chico dropped him to the ground he crawled to the ten Dyaks and snuggled in among their half-naked bodies in a vain attempt to ease the fear which gripped his heart.

"We had better leave them alone," said Temple-ton. "They won't get their wits till daylight. When morning comes I'll give Gung a taste of a switch that will stop him from putting over any more of his yellow-press stories while we're in this neighbourhood."

We sat down upon a boulder and watched the fear-stricken eleven. They writhed and twisted like a bunch of water snakes, each trying to get in the middle of the clump, as if possessed of the idea that the middle man could derive a feeling of security from the knowledge that his companions were around him. And those movements seemed to charge the night with a sense of dread in the same manner that an impending thunderstorm affects the atmosphere. Red Templeton felt uneasy, Chico hugged his rifle and watched the surrounding jungle, and I heaped silent curses upon the head of Gung, who seemed to be a breeding-ground for fear, the germs of which he spread broadcast each time he opened his mouth. I have never heard a storyteller like Gung. Every word he uttered was a cloak under which Terror invaded the mind of the listener, and we had no blame for the half score of Dyaks that he had made crazy with his stories.

"Gung has started all the trouble," muttered Templeton. "This mob will be in a nice state for marching to-morrow, eh?"

"I think it would be good business to shift camp now," said Chico. "This patch of sand has something about it that they don't like, and if we could move them on we might quiet them down."

"That's true," cried Red. "We'll have another try to get them on their feet."

We struggled until we were exhausted trying to bring the natives to their senses. Chico Morgan and Templeton dragged them to their feet, while I tried to hold them there, but it was no use. Fear had loosened the muscles of their legs, and again and again they slipped through our hands and tied themselves into a knot of greasy limbs that defied all our efforts.

"Give it up," ordered Templeton. "It's too late to move now. The moon is setting."

"I hope this game doesn't become chronic with them," growled Chico, as we went to our seats on the big boulder. "I'm as sleepy as a sloth."

"Turn in," said Red. "I'll watch this lot for a while. They'll get tired soon and they'll go off to sleep. You get a nap, too, Lenford. There's no need for the three of us to remain awake."

Chico and I went back to our blankets, and in spite of the groaning of the natives, we were asleep in half a minute. Sleep is more powerful than fear. When a man has been climbing over rough country for a day it requires something more than a feeling of insecurity to keep him awake. We had no knowledge of the White Mias outside Gung's stories, and we had the conceit of the white race which made us turn a deaf ear to anything that was beyond our own experiences. With the matter of the Chalice of Everlasting Flame and the Great Parang it was different. We knew of that cup. Every breeze that blew from nipa-palm kampongs and lonely jungle huts carried some legend of the Wonderful Chalice and Sword, but Gung was the first to tell of the White Mias.

It was the sound of Templeton's revolver that brought Chico and me to our feet. It seemed as if we had been asleep only five minutes, yet the moon had disappeared when we looked around, and the sandy stretch that was named the Place of Evil Winds was as dark as the Caves of Beli. We couldn't see Templeton or the Dyaks, but the yelling of the natives made it easy to locate them.

"Where are you, Templeton?" cried Chico.

"Here," answered Red.

"What's wrong?"

"Nothing much. Something moved here to the right, and I took a shot at it."

"Do you see anything?" asked Morgan.

"No, but I hit it. If you look out! Morgan! Look out!"

I've tried to develop the mental film which recorded the happenings of the two minutes that passed after Red Templeton gave his shout of warning. I am afraid to put my blurred impressions upon paper, but I must. If the moon had been above the horizon we could have seen, but as there was no light we could only feel with our skins and sniff with our nostrils.

All I know is that something came from the jungle in our rear, something that swept over us like a wave of hairy bodies. Great God! what a sensation of horror that charge produced! Our souls seemed to shrink in terror from contact with the clawing, screaming mass that surged over us, and each time a body touched us it produced a physical revulsion that we had never experienced before. That in itself was extraordinary. The touch of an orang-utan in the darkness might well occasion fear, but the touch of that mass created a sick feeling that seemed to be a terror of the soul more than a terror of the body. Perhaps the atmosphere created by the moaning of Gung and the ten Dyaks might have had something to do with this, but I know that Templeton, Morgan, and myself experienced sensations that were hard to analyze as we were buffeted by flying bodies and clawed at by invisible paws.

Red Templeton fired twice, Chico three times, while I took a shot at the rear of the wave after I had been knocked backward by a collision with a flying body. It was when I fired that I saw the streak of white.

It passed before me and the flash of Morgan's rifle revealed it to me. And that flash of white that brought Gung's story to my mind was the tail end of the procession. Stunned and stupefied, we stood and listened to the thumping of heavy bodies on the sand, the crashing of boughs as the wave hit the fringe of the jungle, and then, as if the noise of the animals had prevented us from hearing other noises, we woke up to the fact that the screams of the Dyaks came from a great distance, and were gradually growing fainter.

"Where are you, Morgan?" roared Templeton. "Quick, man! the brutes have stampeded the Dyaks!"

"They've taken the back trail!" cried Chico. "Come on! We might catch up with them!"

Chico started running in the direction we had come from on the previous afternoon, and Red Templeton and I ran behind him at full speed. The Dyaks had stampeded. They had held their ground during the early evening because they were in doubt as to which way to go in order to dodge the thing they dreaded, but the moment the wave of hairy bodies had struck us, they had fled.

We ran for hours. Now and then we thought we heard a yell from the natives somewhere far in advance of us, but when we stopped to listen, we could hear nothing but the sighing of the wind in the jungle. Gung and his half score were on their way back to the headwaters of the Barito, and they were making good speed.

"It's no use!" cried Red. "We've lost them."

He flung himself on the ground, and Chico and I stretched ourselves beside him. We were exhausted after that run.

"It will be dawn in a few hours," said Templeton. "Let us have a sleep and then get back to the camp in the daylight."

"Right," muttered Chico, and without a thought of the dangers that lay in front of us or the arduous work which we would be compelled to perform now that the carriers had deserted, we fell asleep. The sight of the Chalice of Everlasting Fire and the stories of the Great Sword had created a fever within our brains that made us oblivious to dangers that would have disheartened us if we had not seen the cup or listened to the stories of the Great Parang. We could not turn back. An indescribable feeling urged us forward, a feeling that mere treasure was incapable of bringing to our minds. Across the China Sea were millions of people waiting for the great blade that had been carried into the hills when the Orang Bukkit tribes had captured the mutineers of Enrique de Gama, and it seemed as if their longings to see the sword were pushing us into the untravelled and mysterious land that stretched before us.

A Cross In The Jungle

THE most wonderful dawn that ever stained the heavens greeted us

the morning after the stampede. Heavenly geysers flooded the

pearl-gray bowl above our heads with rivers of orange and chrome,

baby-pink and carmine, and we sat and watched the sight. The

mountains of Tawah looked like a fringe of blue chiffon tacked upon

the cloth of gold and orange which was flung across the eastern

sky.

"Come on," said Templeton, after we had sat for some twenty minutes gazing at the sight. "That sky is mighty beautiful, but we're close to something that is so wonderful that three hundred million people will go insane when they hear that it is in our possession."

We didn't need any further prompting. Dawn or Dyaks or anything else could not pull us' from the purpose of the trip, and without a word we started back over the ground we had covered when pursuing Gung and the startled carriers.

We struck the camp about nine o'clock and as we walked across the gray sand stretch, Chico pointed ahead to an object that lay between the camp and the jungle.

"We've got one trophy," he said. "Look!"

We hurried across to the thing that lay upon the sand, and we walked around it in silence. It was an enormous orang-utan, larger than any we had ever seen or read of. The rifle bullet that had ended his mad charge had struck him between the small eyes, and he had fallen backward, the tremendous arms clutching at the sand in his death agony. The big chest of the brute was covered with coarse red hair that was fully eighteen inches in length, while the teeth, stained black with the juices of fruit and vegetables, were showing under the thick lips.

"A nice visitor to come hopping over one's camp in the dark," said Morgan, kicking the big carcass. "If you had turned up in daylight, you brute, we might have kept our niggers with us. Now we'll have to pack our own provisions because you had no idea of social etiquette."

We cooked and ate our breakfast, then sorted out our baggage, left what we could not carry, and turned our faces to the jungle. It was useless attempting to cache what we could not take with us as it was impossible for us to say by what route we would return to the Barito River, and we guessed that the orang-utans would make short work of a cache if we took the trouble to construct one. Besides, we had a firm conviction that we would not starve while we had ammunition, so we shouldered our packs cheerfully and walked forward. Like Jason, of old, we thought only of the thing we had set out to seek, and the pictures of the Great Parang that were in our minds blotted out the dangers which lay in our path. Now and then I shuddered as I looked around at the encompassing jungle and thought over Gung's stories, but I am absolutely certain that Chico Morgan and Red Templeton had no fear. No bigger men ever invaded unknown country than those two, and I am sure that they had forgotten the orang-utan incident long before noon on the day following.

It was a little after noon when we made a discovery. Red Templeton, in endeavouring to get a shot at a wild pig, dived into a thick mass of sandalwood trees, and it was his shout that brought Chico and me to his side. Red was standing still and contemplating a rough cross of stone that stood in a tiny clearing in the centre of the tree cluster!

The cross was about four feet high, built, excepting the crosspiece, of small stones that had become moss-grown through the years. The crosspiece was a single slab of sandstone that had been roughly chiselled, and that, too, showed that many a year of rain and sunshine had passed over it since it had been placed in position.

"Great Scott!" exclaimed Chico. "Did any one Say, we're pretty close!"

He looked at Templeton, and the Englishman nodded.

"Closer than we thought."

"Sure," said Chico. "Why, we might have blundered into trouble if you hadn't noticed this. Gung must have made a mistake about the distance."

"We might be miles away yet," said the Britisher. "Whoever built this wouldn't put it up close to the kampong of the Dyaks. This is, or was, a little private chapel as old as St. Paul's or older."

It was peculiar what effect that emblem of Christianity had upon us as we stood and stared at it. If we had come face to face with a carven Buddha or a rude representation of a two-headed wood devil, we would not have been surprised, but the lonely emblem of the Crucifixion clutched at our throats as we walked around it. It seemed to throw a peculiar atmosphere over the little clearing in the tree clump, and it seemed to our startled eyes that it held within its moss-grown stones the hopes and fears of those who had prayed before it in that place of silence and gloom. It was a splendid outpost of civilization, and in the minutes that we stood silently around it, our thoughts went flying back to places that were thousands of miles from that lonely cross.

Templeton examined the stones carefully in an effort to find some date or word that would show whether the cross had been erected by one of the mutinous sailors of the galleon of Enrique de Gama, or by one of their descendants, but there were no marks to identify the architect. He had built it, prayed before it, and had gone the way of all flesh.

"P'raps the tribe has shifted miles from this point since this was erected," said Chico. "The hill Dyaks are great wanderers."

"That's a fact," admitted Templeton. "We may be a long distance from the goal. It's a pity Gung bolted with the carriers."

With our eyes upon the cross we circled it slowly, viewing it from all points and wondering stupidly concerning the man or men who had erected it. If they were the sailors of Enrique de Gama who had put a dying message upon the bottom of the Chalice of Everlasting Fire, the stone cross was proof that they had not been butchered by their captors. And if it had been erected by De Gama's men, it proved that they had not been close prisoners of the tribe. The position of the moss-covered emblem of faith seemed to suggest a desire for privacy on the part of the builder, since the century old trees that surrounded the spot gave visible proof that no Dyak village had occupied the site since the erection of the cross.

"But it wouldn't have remained in good order all these years," said Templeton, pausing to survey it closely. "Why, there's not a loose stone around the base. If it had been built by one of the Portuguese sailors it would have been laid flat unless it had been cared for. If there——"

Red stopped as Chico gave a little cry of joy. Morgan was on his knees examining the ground at a spot about twenty feet from the base of the cross, and as we hurried to his side we saw the reason for the cry. Templeton's argument was good. The cross would have probably fallen to pieces through the years if others had not looked after it, and when we stood beside Chico Morgan we felt that we were on the point of finding out something about those who had kept the stones together. Chico was kneeling beside a beaten patch of earth about two feet square, and leading back from that patch, stretching away into the jungle, was a faint trail!

That little track was hardly more distinct than the path which a leopard beats to his favourite watering place, but we knew that no animal had made it. The beaten circle at the end of the path told its story. The person or persons who had worshipped in that silent grove had walked to that little circle, contemplated the cross at a distance, and had then retired along the trail by which they had come.

"By George!" gasped Templeton. "What do you make of it?"

"That some one still holds the cross in reverence," answered Chico. "Either some of the descendants of your Portuguese sailors are familiar with its meaning, or the Dyaks, ignorant of what it stands for, have set it up as a fetish. Some one has been in the habit of coming here, and that some one has been here recently."

"What do you mean by recently?" asked Templeton.

"Inside twenty-four hours," answered Morgan. "The tracks are fresh. Feet in leather sandals, and small feet at that."

The big Englishman whistled softly as we stood and looked at each other. We felt that we were on the verge of a tremendous discovery, and we stared at the stone cross as if we doubted our eyes. We could hardly believe that any descendant of De Gama's sailors would understand the significance of the moss-grown emblem, and yet there was proof that some one had been in the habit of approaching that little pile of stones, standing on the bare, beaten circle, and then retreating by the same path over which he had approached.

Chico spoke after a short silence. "Were there any women aboard the Portuguese ship?" he asked.

"Couldn't answer that," said Templeton. "There might have been, but the betting is against it. Enrique was little short of a pirate, I guess, and his boat would hardly be the place for ladies. In those days, a captain who wandered into these seas came with the intention of picking up all the loot he could get his hands on, and he trusted to Providence and the fighting strength of his crew to cut his way back to the west."

"It's a puzzle," muttered Chico. "How the dickens——"

A wild pig broke through the underbrush close to the spot where the little path went burrowing into the jungle, scampered across the clearing, and disappeared. Another followed, and Templeton sprang behind a creeper growth that covered a stunted mohor tree.

"Quick!" he whispered. "Some one is coming!"

We dived behind the green screen, and from tiny peepholes watched the path. Some one had startled the wild pigs, and we imagined that the person approaching was the one whose feet had beaten the little path to the cross.

With straining ears we listened for a sound while our eyes were glued upon the path. Now and then we heard the snapping of a twig or the rustle of dead leaves, but we could see nothing. If some one were approaching—and we felt certain that a human being was near—the approaching one was not using the little path. He was pushing his way through the undergrowth, and he was using extreme caution in doing so. If the wild pigs had not alarmed us, it is certain that we should not have noticed the slight noises which came to our ears.

The little noises of snapping twigs and rustling leaves ceased, and in the silence that followed Templeton lifted a warning finger and pointed through his spyhole at a place on the opposite side of the clearing. For a minute Morgan and I could see nothing, then our eyes pounced upon the spot that Templeton had located. Thrust through the foliage was the yellowish-brown face of a Kyan, his beady, black eyes searching the little clearing in which stood the lonely moss-covered cross!

The examination was thorough. As the sharp eyes passed over the screen of leaves which concealed us from view, we drew back quickly, wondering for an instant if the instinct of the savage would tell him of our presence, but the next moment we were reassured. The native stepped into the open, and we had a full view.

He was a tall, muscular Kyan, wearing a chawat of bark cloth around his loins, half a dozen fibre rings around each ankle, and a score of shell bracelets upon the right wrist. He carried a wooden shield, the front of which was decorated with some twoscore tufts of human hair, and in his right hand he gripped the deadly blowpipe. His thighs were tattooed with spiral designs that we had never seen upon any of the coast Dyaks, and his body was streaked with white clay, the streaks radiating from a charm that hung upon his chest. Altogether he struck us as being a fierce-looking specimen, and the bunches of human hair that flapped up and down upon his shield did not impress us in his favour as he walked forward.

He stopped when he reached the bare spot at the end of the path where we had stood a few moments before, and he was on the point of stooping to examine the ground when his keen ears warned him that the moment was not opportune. With a single bound he sprang back to his hiding-place, and we turned our eyes upon the path. And this time we seemed to know that the person who regularly visited the cross was approaching by the narrow path through the jungle.

If I live through the next century, I shall never forget that first view of Nao, the Golden One. I couldn't forget it. She stood in a frame of green, and for a moment we thought that she was a wood nymph belonging to the dark woods of tapang and sandalwood. Diana of old was never more radiantly beautiful or full of life. As we stared, forgetful for the moment of the wild-looking Kyan who had plunged into the undergrowth, we thought of her as the spirit of the hills, the living embodiment of the good that was in that uncharted jungle. She was a wonder woman.

Taller than the ordinary woman, she possessed, with the unusual height, all the grace and suppleness of the jungle-born. She wore a small kabayah, or jacket, cut low around the neck and barely covering the breasts, together with a sarong or petticoat, that was wound around the waist. Between the kabayah and the sarong she wore, Dyak fashion, a dozen girdles of cane that were so completely covered with tiny gold rings that none of the cane was visible. The sarong was blue, a beautiful Venetian blue, and it was edged with tiny pearls and turquoises. Her hair hung in' two great plaits, while the black masses above her brow were held back by a silver comb of native workmanship, in which a ruby glowed like the eye of an aintu, or hill spirit.

The face of the girl was more beautiful than any face we had ever seen. She was beauty itself. All the witchery and dreaminess of the Orient were in the big dark eyes that were deeper than the whirlpool of San Larn. The nose was exquisitely modelled, the lips redder than the blush upon Mount Pemabo when the sun kisses it as he comes up out of the Celebes Sea. By the glory of Solomon! she was a magnificent woman. The sight of her gripped us like the clutch of death itself, and we looked upon her beauty with eyes that made the brain forget everything else.

Her two slim hands held back the green branches while her eyes looked at the cross. Her nostrils seemed to be sniffing the air like a mountain deer that suspects danger, and I know that in the moment she stood at the edge of the clearing, like a perfect statue, a horror lest she should turn and flee came upon us.

Chico Morgan gave a little sigh of relief as one of the small feet in its curious sandal of pigskin was put forward haltingly. It seemed as if the girl sensed danger, but that she was attempting to throw off the dread brought to her by her skin. Slowly, very slowly, she advanced toward the cross, and if we doubted whether the person who made that path understood the significance of the little pile of stones, the doubt fled from our minds as we watched her face.

The heathen approaches his fetish with a look of fear upon his face, but there was no fear upon the face of the Golden One. Her eyes were the eyes of a trusting worshipper, and as we looked at those eyes we seemed to see the girl's naked soul. I think we witnessed a miracle just then. Up in that jungle that was more inaccessible than the Gidi Desert or the slopes of the Nan Shan Mountains, a woman was clinging to a belief that refused to die. As we looked at her we thought of the three hundred years that had elapsed since the Portuguese sailors of Enrique de Gama had been taken into the hills as the prisoners of the Orang Bukkit, and we seemed to read the past in the big eyes that were soft and limpid as they looked upon the cross. We saw it all. Through the centuries a belief had lived, and we thrilled as we peered at her from our leafy shelter. One of De Gama's sailors or officers had erected that cross in the jungle, and generation after generation had come to pray before it. The knowledge choked us. We pictured those descendants coming to that spot, drawn there by the germ of belief planted in the subconscious brain, their knowledge of the faith growing less with each succeeding generation. It was an extraordinary happening. We stared at the girl in the clearing and wondered as to her knowledge of the symbol that had been set up in that lonely spot in the jungle.

The red lips moved, and a prayer as soft as the flutter of an angel's wing went out into the stillness. Red Templeton's head was thrust forward to catch the whispered words, and the look of amazement upon his sun-tanned face deepened as he caught the whisper. Chico and I glanced at Red, and we knew well that he understood the language in which the invocation was couched.

Softly, ever so softly, the woman sent her little supplication into the silence, and a feeling of shame gripped us as we listened. The place was as holy as a church, and we were listening to the prayer of a girl whose kabayah heaved and fell under the stress of her emotions.

Suddenly Chico Morgan shifted his position. His right hand was thrust through the curtain of green, his Colt shattered the stillness of the place, and before Templeton or I could bring our thoughts back to the incident that had preceeded the arrival of the girl, the Kyan warrior stumbled out of the bushes and fell full length upon the grass. We understood then why Chico had fired. Although mortally wounded, the native made an attempt to turn the deadly blowpipe upon the girl as he threshed around in his death agony.

We Take Another Partner

IT was strange how the intuition of the girl enabled her to take in

the situation the moment Chico fired the shot. Probably she had

never heard the report of a gun in her life, yet when she glanced

at the Kyan clutching the grass in his death struggles, and then at

Templeton, Chico, and myself, she understood immediately. And she

understood more. Without one of us making a move to enlighten her,

she knew that it was Morgan who had killed the would-be assassin,

and with a little cry of thankfulness she fell upon her knees and

kissed the hand that held the revolver.

She fell upon her knees and kissed the hand that held the revolver.

Chico blushed like a schoolgirl as he listened to the torrent of words that fell from the red lips, and he turned helplessly to Templeton as he lifted the girl to her feet.

"What does she speak?" he cried. "Portuguese, isn't it? Tell her it was nothing! Don't stand and stare at her, man!" Red Templeton jerked himself out of the trance into which he seemed to slip when he heard the girl whisper her prayer to the cross. He fired a question at her in Portuguese, and after a moment's hesitation she answered it. Chico and I stood and stared at that vision with open mouths as she spoke rapidly. That happening was something that would amaze the greatest stoic that ever lived. We had struck a link with the past, and as we looked at Templeton, we saw that her words stirred him in a way that made us madly excited to hear them translated.

"What is it?" cried Morgan. "Don't keep us waiting! Tell us!"

The girl was still clinging to Chico's hand, and she seemed to cling tighter as Red swung round upon us.

"By all that is wonderful! we've struck it!" he cried. "It's amazing! She speaks a mixture of Portuguese and Malay, and I'll swear to heaven she's a descendant of Enrique de Gama's sailors!"

"But what does she say?" asked Chico. "Why does she point to the back trail?"

"She wants us to clear out at once," answered Templeton.

"Why?"

Red took a glance around, then at the Kyan upon the ground. "We're close to the kampong of the Spotted Panther," he said. "Do you hear me? She says it's close, and she wants us to clear out before he gets his eyes upon us."

"Does she stay there?" questioned Chico.

"Yes. Wait a moment and I'll ask her about the treasure."

Templeton opened his mouth to put a question concerning the Sword of Buddha, but Chico clutched his arm. "Don't ask her any questions about that!" he cried. "That wouldn't be fair play!"

"Why?" asked Red.

"She is with them," snapped Morgan. "And we don't want to burrow secrets out of her because we stopped the Kyan with the blowpipe."

Templeton and Chico looked at each other, and the girl watched them with her big eyes. And she seemed to divine the cause of their little disagreement at that moment. It was wonderful. With a sudden twist of her arm she tore the big ruby comb from the hair that was blacker than the Jade Goddess of Sarm, and she thrust the thing into Morgan's hand as she talked rapidly.

"Now she's talking treasure," said Red. "She senses the reason that brought us up here, and she wants you to take the big ruby and go back."

Chico smiled gently as he put the comb back into the girl's hand. "Tell her we are not going back," he said. "We are going straight ahead if there are a dozen Spotted Panthers in the way. And tell her it will be better for her to break connections with us right now."

"What's the hurry?" asked Templeton.

"What's the hurry?" repeated Chico. "We don't want to make her a traitor, do we? Let her go her own way and we'll go ours."

Red smiled as he turned to the girl with the message. Morgan was sensitive about receiving any information from the beautiful stranger, but the Britisher couldn't see matters in the same light. We had come up to that place with the intention of looting what the Orang Bukkit tribe had looted from the Portuguese ship three hundred years before, and Templeton didn't care how we got the information as long as we got it.

But he translated Chico's message to the girl. We knew that by the manner in which she acted after the Englishman spoke. Morgan's hand was taken in a tight grip between her two small ones, and she hurled a torrent of words at Templeton.

"She won't leave us," said Red, translating rapidly. "You won her over by putting a bullet in the head of the gentleman who tried to assassinate her. He's a Tring, and they're at war with the tribe bossed by the Spotted Panther. This girl's name is Nao, or the Golden One, and there are three others in the kampong that speak Portuguese."

Chico tried to disengage his hand, but the Golden One would not be shaken off, and Chico's tanned face reddened. I think the big American would have turned and run away had it not been for the fact that the stone cross in the grove of sandalwood trees, together with the appearance of the girl, convinced us that we were close to the Great Parang of Buddha, and the feeling stirred a madness in us that made it impossible for us to retreat. The fever caused by the discovery of the cross made us forget the affair of the previous night, and it worked us up to such a pitch of excitement that we were incapable of forming any idea of the dangers that lay in front of us.

"If we are going forward she intends to stick to us and help us all she can," said Templeton. "That is what she says. What's the use of your kicking against fate? I've told her what we're after and it doesn't surprise her. Why, man, she must be the descendant of an officer of De Gama's. An officer, not a common sailor! I'll swear she is! And if the truth were known, the best part of the treasure that is supposed to be in these hills should belong to her!

"There's a lot of sense in that argument," said Chico. "I guess she's the rightful claimant to the most of it. That is, if we acknowledge the right of Enrique de Gama to it in the first instance."

We stood and looked at each other and the girl. Whoever named her the Golden One named her well. There were depths in her eyes that held all the glamour and wonder of the world. Saints be praised! wasn't she beautiful! She seemed to be as old as the hills and yet as young as the dawn. And she had the mystery of all women. One would think that her eyes were the eyes of Helen, yet her face had the purity of St. Monica's.

And she seemed to understand the matter that was in dispute at that moment. I don't know how she gripped it, but I know that she did. We have little knowledge of the inherited impressions that are stored in the cells of the brain and we were ignorant of the thoughts that welled up in the mind of that girl when she got the first glimpse of us. She was looking backward, straining after words that had escaped her, searching for memories that had been lost through the years. God alone knows how she struggled to make the hazy dreams seem real; to build up the bridges that made connections with a past that she had been robbed of by fate.

Suddenly she sprang erect, made a rush toward the moss-grown cross, touched it daintily with her fingers, then slipping back to the spot where we stood she touched our hands in turn, as she made verbal explanation to Templeton and signalled that he translate for Chico and me.

"She says that the cross binds the four of us together," said Red, half choking with emotion as he spoke. "Saints be praised! what has this girl dreamed of in this infernal place?"

The eyes of Nao flashed as a phrase seemed to spring out of the mental reticule into which words had fallen through disuse. She opened her mouth to speak, lost the phrase, waited an instant, then in exultation she seized Templeton by the sleeve as the forgotten words were recalled.

"A cruz de Deus traz-nos todos unidos!" cried Nao, repeating again and again the words which Templeton had translated, and pointing as she spoke toward the cross. And her voice thrilled us.

The Golden One put out a little hand to Chico, and Morgan took the small fingers, lifted them to his lips and kissed them. And she stood like a princess while he tendered the salute. Breeding? Of course there was breeding! I'll wager that some of the bluest blood in old Portugal was with Enrique de Gama, and that blood showed in the actions of the girl, who was fairer than the houris who wait to open the door of the Mahommedan paradise. She swept us off our feet at that moment. She was our kin, and by the bones of Tamerlane she seemed to become regal when she spoke to us. If we had met her on the Praco do Rocio at Lisbon in conventional dress we should have thought her some blue-blooded beauty from the big houses on the Avenida da Liberdade. If Enrique de Gama hadn't any aristocratic names on his register, we guessed that the long-dead Portuguese, from whom Nao was descended, must have shipped under an alias.

"Nos somos amigos," she murmured.

"She is asking if we will be friends," said Templeton.

"Friends?" repeated Chico. "Ay! till we die! And we'll get the Parang of Buddha and all the other loot, and you'll share in it. And we'll take you back to where you belong. We will! Back to the lemon and the orange groves of Lisbon and the moonlit nights and the tinkling guitars. By the powers above we will!"